Plant Pairings within the Kumulipo

by

“Holding Sway: Seaweeds and the Politics of Form” is a series of photo essays that channels a visual curiosity about seaweeds with considerations of militarization, gender, Indigenous sovereignty, extractive regimes, and climate change. Foundry guest editors Melody Jue and Maya Weeks invited participants to create or curate images that literally and figuratively “hold sway” in two senses: capturing the attention of an audience, or conveying a relationship of being in touch with seaweeds by holding their swaying botanical forms.

“My response to these disappearing organisms is to create records of their existence and to raise questions about their historical, cultural, and ecological significance, especially in relation to climate change and global warming.”

Seaweed, or limu as it is known in Hawai‘i, has always played an important role in the life of Hawaiians. In her book Lā‘au Hawai‘i, Dr. Isabella Abbott remarks, “Hawaiian understanding of their plants and handling of plant varieties to suit different ecological niches available on each island enabled them to reap abundant harvest from limited cropland with considerable certainty.” One of the most important foods (and in ancient times, the most consumed item after kalo and fish), limu also plays a significant role in cultural practices. Limu kala (Sargassum echinocarpum) as it is known in Hawaiian, means to forgive, let go, or absolve, and it factors significantly in the practice of ho‘oponopono, a ceremony of reconciliation. The use of limu kala along with prayer seeks forgiveness of wrongdoing to cleanse the mind and heart. In healing, Gutmanis describes how practitioners of lā‘au lapa‘au (Hawaiian herbal medicine) knew the body could not be healed unless the mind was ready to release its suffering, and would often create a lei of limu kala to be worn by the patient into the ocean, where the lei loosened and floated away, taking with it the emotional and mental vestiges that caused the suffering and created illness, allowing the body to heal.

Once an abundant resource in Hawai‘i, much of the limu has disappeared due to over-harvesting, warming ocean temperatures, aggressive alien seaweeds, and polluted runoff. My response to these disappearing organisms is to create records of their existence and to raise questions about their historical, cultural, and ecological significance, especially in relation to climate change and global warming. As a student of Hawaiian ethnobotany, I have gained an ardent respect for the subtleties with which native Hawaiians observe the world around them. This knowledge has informed a deeper sensitivity to my environment, and inspired new avenues of self-expression. The flora and fauna found in the fragile ecosystems once so vibrant with life, and so devastated by extinction, has led me to a greater understanding of the island home where I live. I hope to inspire fresh perspectives and an awareness of the reciprocal relationship that Hawaiians have to the ‘āina (the land). This understanding can serve as a reminder that we are all connected—“we’re all interrelated members of an organic cosmos.”

“The Kumulipo is a poetic verse, set in a rhythmic chant that outlines the privileged role and responsibility that humans have within the earth ecosystem.”

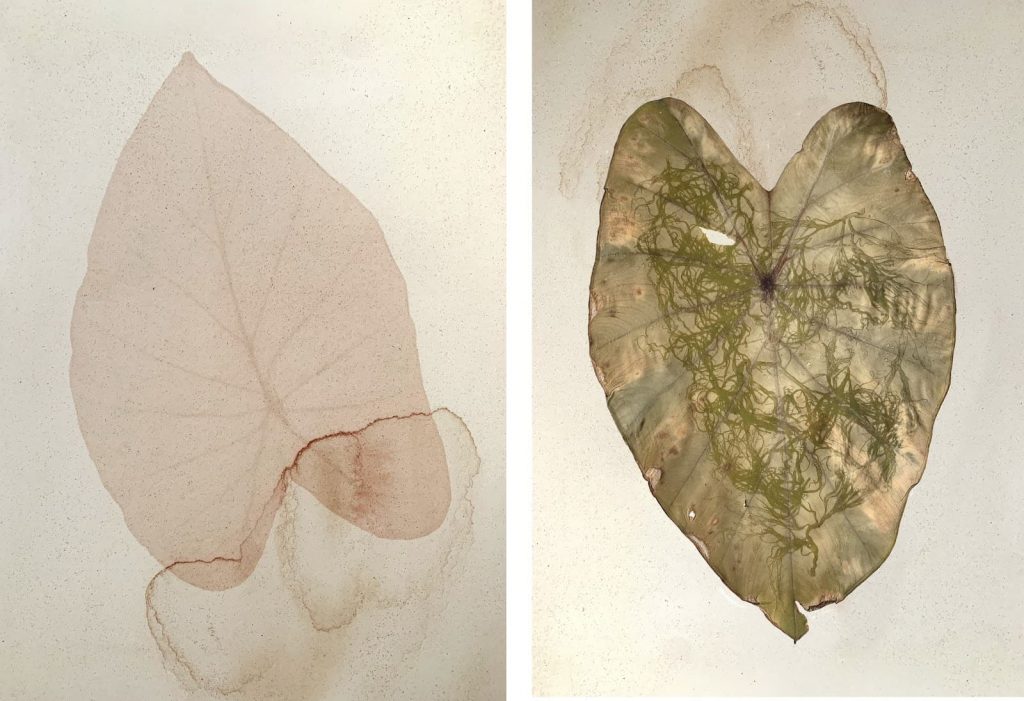

In my attempt to acknowledge the beauty and acuity found in the Kumulipo, a Hawaiian creation chant, the following images represent my interpretation of the symbiotic plant pairings found in its verses. My process of creating the images began with learning to identify each plant, and then finding and collecting a sample of each. The land and sea plants chosen for the prints were those that could be found in nature—many of the plants have become increasingly rare—far less likely growing in Hawai‘i nei (this beloved Hawai‘i) than when the Kumulipo was translated in the eighteenth century.

To print the land plant, a light-sensitive emulsion was made from red limu hā‘ula (Amansia glomerata), coated onto paper, and printed as an anthotype. This method of printing is known as a contact print; the plant material is placed onto the light sensitive paper and laid in the sun. Ultraviolet light bleaches away the exposed area of the paper, leaving behind an imprint of the leaf that masked the light. The accompanying sea plant is printed as a chlorophyll print; the plant material is laid directly onto the leaf of the land plant and put into the sun. Once again, ultraviolet light then bleaches away the exposed area of the leaf, leaving behind an imprint of the plant that masked the light. This process reflects the form of the Kumulipo.

The Kumulipo is a poetic verse, set in a rhythmic chant that outlines the privileged role and responsibility that humans have within the earth ecosystem. Describing the emergence of all the elements within the universe, including humankind, it “articulates and reveals the connections of the sky and earth, the earth and ocean, the ocean and land, the land and man, man and gods and returns again to repeat the interrelationship of all things is an everlasting continuum, it is Ponahakeola, the chaotic whirlwind of life.” The chant, composed of over two thousand lines, is sectioned into sixteen wā (eras). Beginning with the description of a large shift in the evolutionary process, anthropologist Martha Beckwith describes it as a movement from eternal stillness and darkness until the moment when creation emerges.

At the time that turned the heat of the earth,

At the time when the heavens turned and changed,

At the time when the light of the sun was subdued

To cause light to break forth,

At the time of the night of Makalii (winter)

Then began the slime which established the earth,

The source of deepest darkness.

Of the depth of darkness, of the depth of darkness,

Of the darkness of the sun, in the depth of night,

It is night,

So was night born.

Kumulipo was born in the night, a male.

Poele was born in the night, a female.

The Hawaiian concept of duality is prevalent throughout the chant. For each land plant listed, there is an accompanying marine plant. These lists of pairs continue, illustrating the process of life as it goes through the stages of creation, similar to a human child. All plants and animals of land and sea, earth and sky, male and female are brought into being. Beckwith affirms that these pairings, many of which are based on a similarity of form, work together and protect one another. During the process of birth, these elements, and their masculine and feminine essence emerge, and when linked together, form a whole. This progression leads to the creation of early mammals, until a human being is born, Hāloa, the ancestor of all Hawaiian people.

The metaphor of balance found in the Kumulipo, and the duality of opposites—light and dark, female and male, land and sea—show how keenly ancient Hawaiians observed both physical and chemical components of the natural world. Everything in the universe is related and connected—activity or behavior in one area will certainly have consequences in other areas. The poetic verses of the Kumulipo are a reminder that all of life is affected by causality and that decisions we make today will reverberate tomorrow.

The accompanying images I have created are visual interpretations of the second, fifth, and tenth verses of chant one, each pairing a type of limu and a terrestrial plant. This version of the chant was translated into English by Queen Lili‘uokalani during her imprisonment in 1895 at ‘Iolani Palace and afterwards at Washington Place in Honolulu, and was completed in Washington D.C. May 20, 1897.

Second Verse: limu ‘ēkaha (Halimeda kanaloana), and ‘ēkaha fern (Asplenium nidus)

Kane was born to Waiololi, a female to Waiolola.

The Wi was born, the Kiki was its offspring.

The Akaha’s home was the sea;

Guarded by the Ekahakaha that grew in the forest.

A night of flight by noises

Through a channel; water is life to trees;

So the gods may enter, but not man.

Fifth Verse: limu manauea (Gracilaria coronopifolia), and kalo manauea (Colocasia esculenta)

Man by Waiololi, woman by Waiolola,

The Manauea was born and lived in the sea;

Guarded by the Kalo Manauea that grew in the forest.

A night of flight by noises

Through a channel; water is life to trees;

So the gods may enter, but not man.

Tenth Verse: limu kala (Sargassum echinocarpum), and ‘ākala (Rubus hawaiensis)

Man by Waiololi, woman by Waiolola,

The Limukala was born and lived in the sea;

Guarded by the Akala that grew in the forest.

A night of flight by noises

Through a channel; water is life to trees;

So the gods may enter, but not man.

This photo essay is part of the Holding Sway: Seaweeds and the Politics of Form series, funded by UCHRI’s Recasting the Humanities: Foundry Guest Editorship grant.