Unctuous Voices, Seaweed Kinships

by

“Holding Sway: Seaweeds and the Politics of Form” is a series of photo essays that channels a visual curiosity about seaweeds with considerations of militarization, gender, Indigenous sovereignty, extractive regimes, and climate change. Foundry guest editors Melody Jue and Maya Weeks invited participants to create or curate images that literally and figuratively “hold sway” in two senses: capturing the attention of an audience, or conveying a relationship of being in touch with seaweeds by holding their swaying botanical forms.

“A gendered hobby, “seaweeding” was considered a creative pastime of little importance. However, many of the collectors made a significant contribution to marine botany, meticulously recording specimens and sharing their findings generously with the (male) scientific community.”

Unctuous Between Fingers is a creative research project that poses the question, what can we learn from seaweed? The project’s starting point is an archive of pressed seaweeds and algae held by the Royal Albert Memorial Museum, predominantly collected by women in the mid 1800’s. A gendered hobby, “seaweeding” was considered a creative pastime of little importance. However, many of the collectors made a significant contribution to marine botany, meticulously recording specimens and sharing their findings generously with the (male) scientific community.

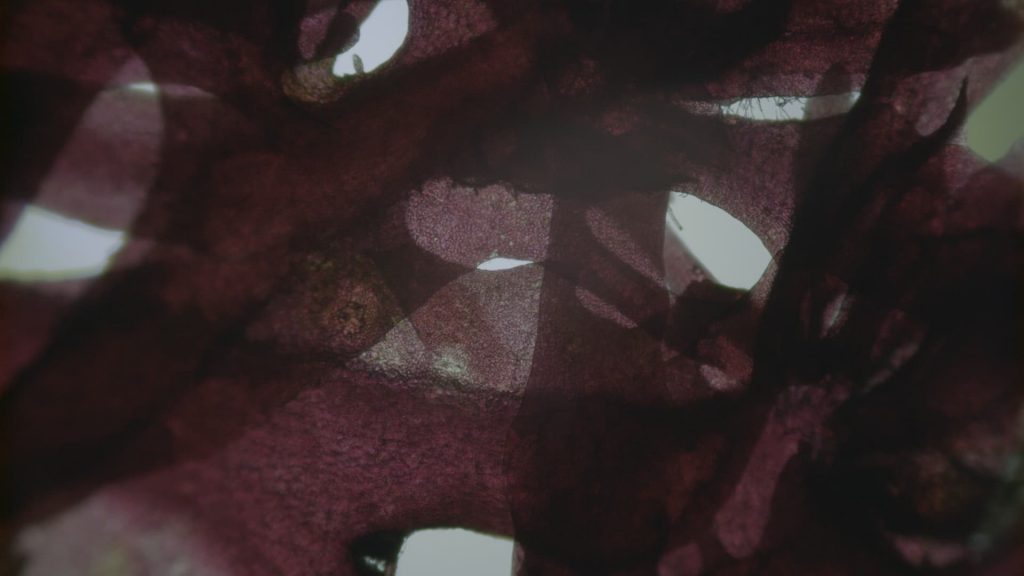

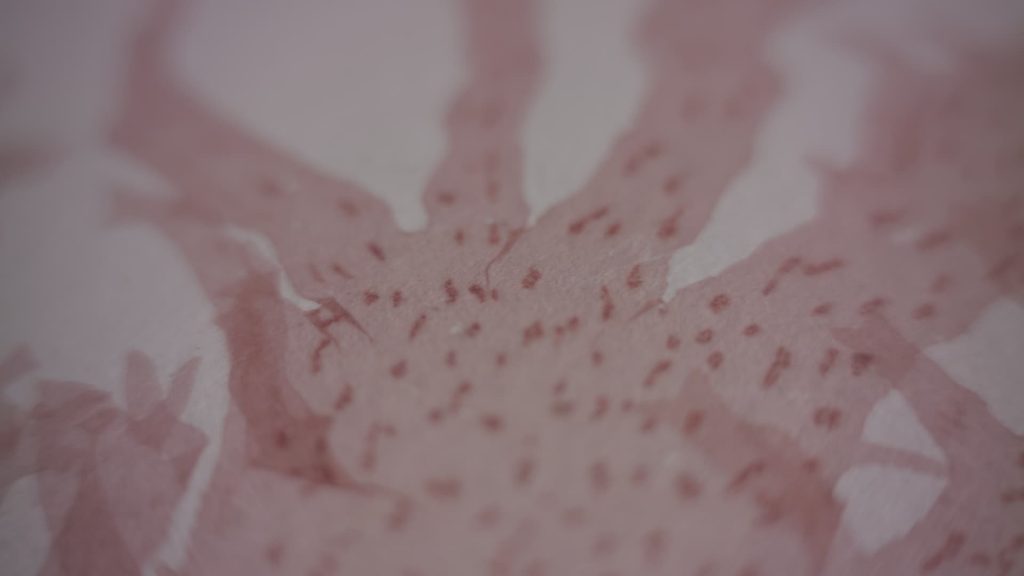

What happens when something slippery, living, and intangible is pressed, dried, and flattened? What do we lose or gain in the process of preserving these specimens and how does this transformation from unctuous and elusive to brittle and flat relate to ideas around collecting, naming and care, and active and historicized feminisms? These questions and provocations resulted in a moving image work, made in collaboration with a group of individuals from a range of disciplines who find affinities, work, inspiration, or joy in seaweed. Nine women—folk who exist in many fields, but sometimes describe themselves as poets, activists, philosophers, dancers, artists, marine biologists, or human geographers, all enthralled in different ways by seaweed—came together for a workshop one day in 2019. Together we touched, smelled, bathed, danced, ate, and read seaweed. We pored over the museum’s seaweed collection, recreated a seaweed’s life cycle with our bodies, wrote, analyzed, collaged, discussed, and laughed a lot.

Zooming in and out in scale, Unctuous Between Fingers tangles together many voices and perspectives, a complex seaweed sisterhood. The project questions seaweed’s materiality, its relationship to care and queerness, the problematics of taxonomy, its life-giving properties, and relationship to speculative feminist futures.

Part 2 of this text is an attempt to foreground some of the many contributions and thoughts that were gathered during the project: from the space of the workshop, in interviews, from commissioned responses to the project, and from key texts that influenced the theoretical framework.

Dani asks me where my holdfast is, what keeps me steady? I stretch out my lamina and reach for the names of the dear ones who ground me.1

Giovanna articulates seaweed’s sisterhood to me, offering words for its complex relationship to gender and solidarities.2

Isabella reminds me that through oral traditions, the Hawaiian names for seaweeds have been stable for centuries, while western identifications constantly shift.3

Sammy joyfully shows me seaweed’s queer kinship, its sentience and potential for healing and resistance.4

Holly reveals that the stories of the women seaweed collectors have mostly been forgotten, but their names (delicately handwritten in faded pencil), survive on the taxonomical sheets in the archive.5

Maria demonstrates that seaweed can be a medium to conjure a future perfect.6

Sarah introduces me to the gloopy, viscous pleasure of serrated wrack, that when immersed in warm water, releases clouds of mucilaginous carbohydrates and spermy orange goo.7

Kayle brings my attention to the need for “subtle shifts in changing how we name, to enable other ways of seeing and other ways of being” to “find how we actually are as a body, rather than how we are classified as a body.”8

Stacy gifts me “trans-corporeality” to describe the inseparability of human and environment, constantly shifting entanglements and volatile actions.

Margaret confides that at 86 her hair is not gray because of the seaweed she eats.9

Angela brings my attention to the problematics of seaweed’s classification by color—the ghost of Linnaeus lurking in the reds, greens, browns.10

Astrida proposes that “co-worlding is always a collaborative process, and always emergent,” that “the thing called ‘the body’ is always on the move.”

Katherine asks me to move like seaweed, to consider the body as stipe, bladder, thallus, to undulate, bob, float with and through water.11

Frankie invites me to read between the lines of “great companions,” a phrase used to describe Victorian seaweeders Amelia and Mary. To acknowledge the queer desire calling from their collections, from the bodies of seaweeds.12

Elizabeth encourages me to look to seaweed for “possibilities for being otherwise.”

This photo essay is part of the Holding Sway: Seaweeds and the Politics of Form series, funded by UCHRI’s Recasting the Humanities: Foundry Guest Editorship grant.

Notes

- In an interview I undertook with Dani Abulhawa on November 26, 2021, she described her movement workshop ‘Move like Seaweed’: “…part of the workshop is to think about the symbolic dimension of seaweed. So what I ask people to consider is the fact that seaweed has this holdfast that anchors it in place, and that enables it to move freely, and then we talk about what aspects within our lives enable us to be rooted and anchored in some way but have that freedom to move.”

- In her article, “Seaweed, soul-ar panels and other entanglements,” Giovanna Di Chiro draws on her background in phycology to think through her work as an environmental justice scholar. She refers to the “seaweed sisterhood” to described the feminist solidarity she encountered with female scientists at UC Santa Cruz.

- “Through oral traditions, the Hawaiian names [for seaweeds] have been perpetuated and usually accurately applied to the individual species.” Isabella Aiona Abbott, Marine red algae of the Hawaiian Islands.

- In 2021 as part of my ongoing project, Unctuous Between Fingers, I commissioned artist and witch Sammy Paloma to make a work in response to the question, “What can we learn from seaweed?” Wet Ceridwen & The Skuzz Nymphs is a text-based horror game that is a kind of devotional. It is a thank you note to the beach, to seaweed, to Annie Sprinkle, to Sammy’s friends, and to the titular Goddess. Featuring queer family hang outs, seaweed monsters, grief rituals, and a good dose of fucking up transphobes.

- In 2019, I was commissioned by the Royal Albert Memorial Museum in Exeter, UK to create an artwork in response to their collections. Scrolling through their object database, I became bewitched by their seaweed archive, sheets of delicately pressed and dried specimens, reds, greens, browns, vivid in color and but flat, fragile and brittle, almost disappearing like ghostly watercolor drawings into mottled paper. After some initial research I noticed that most of the seaweeds were collected by women. Dating from the mid-19th to early-20th century, each specimen bears the collector’s name in pencil alongside the collection date, location, and latin identification: Mrs. Griffiths, Miss Cutler, Miss Mills, Miss Hutchins, Miss Cresswell. Holly Morgenroth, Collections Officer at the Royal Albert Memorial Museum, opened up this world of pressed seaweeds to me, noting how little we knew about most of the lesser-known collectors.

- In 2021, I commissioned artist and scholar Maria Christoforidou to make a work for Unctuous Between Fingers in response to the question, “What can we learn from seaweed?” Spanning poetry and photography, her piece Spontaneous Beings imagines Mary Wildfire Edmonia Lewis (a 19th-century American sculptor of Afro-Caribbean and Native American [Mississauga/Ojibwa] descent) in a future perfect on the coast of Cornwall. Pondering poisons, tasting the seaweed, the testament of the deep, deep secrets Yemaya (Yoruba deity celebrated as the giver of life and the metaphysical mother of all Orisha [deities] within the Yoruba spiritual pantheon) brings to the surface as medicine.

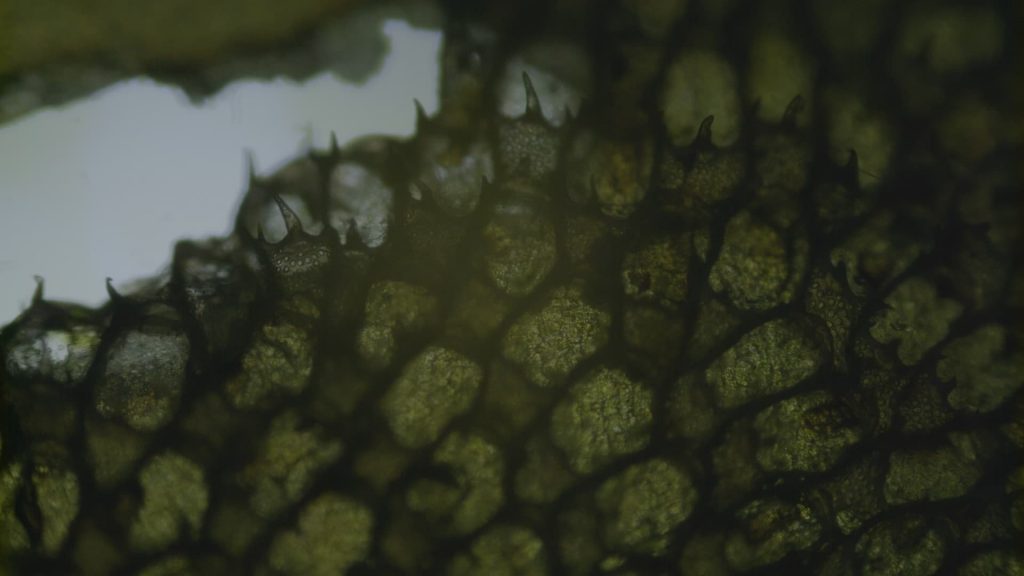

- A November 30, 2022 email from Marine Biologist, Sarah Hotchkiss: “You remember correctly—there were sperm floating around! The seaweed was probably Serrated wrack—very similar to Bladder wrack. It is the main seaweed used in seaweed baths in the UK/Ireland because it readily oozes carbohydrates in the hot water—you will remember the unctuousness!! The plants I collected were fertile—Serrated wrack has separate male & female plants. The male plants develop a deep orange color as they become fertile as the sperm (antherozoids) contain high levels of orange carotenoid pigments…hence the water in our seaweed bath turned orange because the antherozoids also oozed out. The sperm are housed in little pits in the surface of the seaweed—called conceptacles—I remember we even performed a conceptacle ‘dance.’”

- Transcript of a 2019 conversation with artist Kayle Brandon, which forms part of the audio of my moving image work, Unctuous Between Fingers: “There seems to be something connected to bodies, external bodies and naming and pronouns that is really going on for us as a species, and it seems to be affecting how we now feel—in terms of colonization processes…and I think that naming, and how we speak about names, who has the right to name and how names affect how we see is really coming into question. For instance my child says, “What’s that called?” and instead of saying “It’s called a poppy,” you can say, “We call it…we know it by the name of ‘poppy,’” so kind of changing these subtle shifts in how we change how we name, to enable other ways of seeing and other ways of being, and finding how we actually are as a body rather than classified as a body.”

- Margaret Horn, founder of The But ’n’ Ben eatery in Auchmithie, and lifelong seaweed forager and imbiber, shared this insight with me on a guided seaweed foraging walk on the beach at Auchmithie, Angus, Scotland in 2019.

- In 2021, I invited Angela Y. T. Chan to lead a reading group exploring seaweed through an anti-colonial lens. In relation to an excerpt from Sria Chatterjee’s essay, “The Long Shadow Of Colonial Science,” we discussed the relationship between the classification of plants and the classification of humans in the 18th Century.

- A 2019 workshop led by Katherine Hall using somatic exercises to become more seaweed-y. In the same workshop we also re-enacted a seaweed life cycle, becoming a “conceptacle”—see footnote 7 for marine biologist Sarah Hotchkiss’s memory of this.

- “In her book, Sister Arts: The Erotics of Lesbian Landscapes, Lisa Moore has drawn attention to the popularity of such activities, suggesting that they were a way of celebrating partnership and companionship amongst women. Might these ‘friends’ and their activities actually evidence a form of intimacy that contemporary viewers would call queer? Whilst words like ‘lesbian’ and ‘queer’ did not then exist in the way that we use them today, they can still be helpful terms for understanding a longer history of same-sex desire. Moore argues that the ordering of natural history in a domestic setting, like the arranging of algae within a scrapbook, was one way of expressing love for women, and one that has often been overlooked.” Frankie Dytor, “Amelia Griffiths’ seaweed collection.”