Prince of Florence

Prince of Florence was created as a final project for Dr. David Theo Goldberg’s graduate seminar, “Epistemologies of Deception.” Some course readings engaged the everyday, interpersonal variety of deception; others addressed geopolitical deception as a mode of obtaining and maintaining power. Prince of Florence gets its name, in part, from Machiavelli’s The Prince, but references to other course texts are scattered throughout – and a full reading list is reproduced within the game as part of the information under “About.” A central idea that runs through these texts, and one that Dr. Goldberg offers in the reading list’s introductory essay, is the twin nature of secrecy and transparency. Secrets “are made to secrete,” to reveal themselves; transparency “hides secrets in plain sight.”

We chose the form of an interactive fiction text as our final project because of the medium’s capacity for hiding and secreting information. The Easter Egg, for example, showcases this capacity: players search for information with the expectation of encountering something revelatory, something that will open up new paths for story progression. But Easter Eggs are planned, which is to say that they merely offer the illusion of the illicit discovery of extra-narrative information, but the only secrets they can offer are those selected for secretion. Interactive fiction texts succeed when they entice the player to learn that which is not yet discovered, and therefore they hide information with the intent of revealing only some of it.

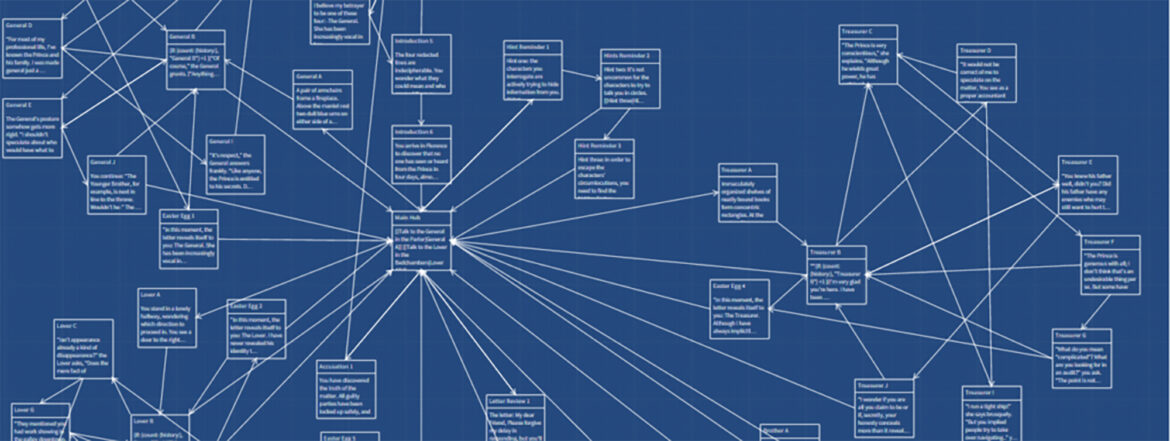

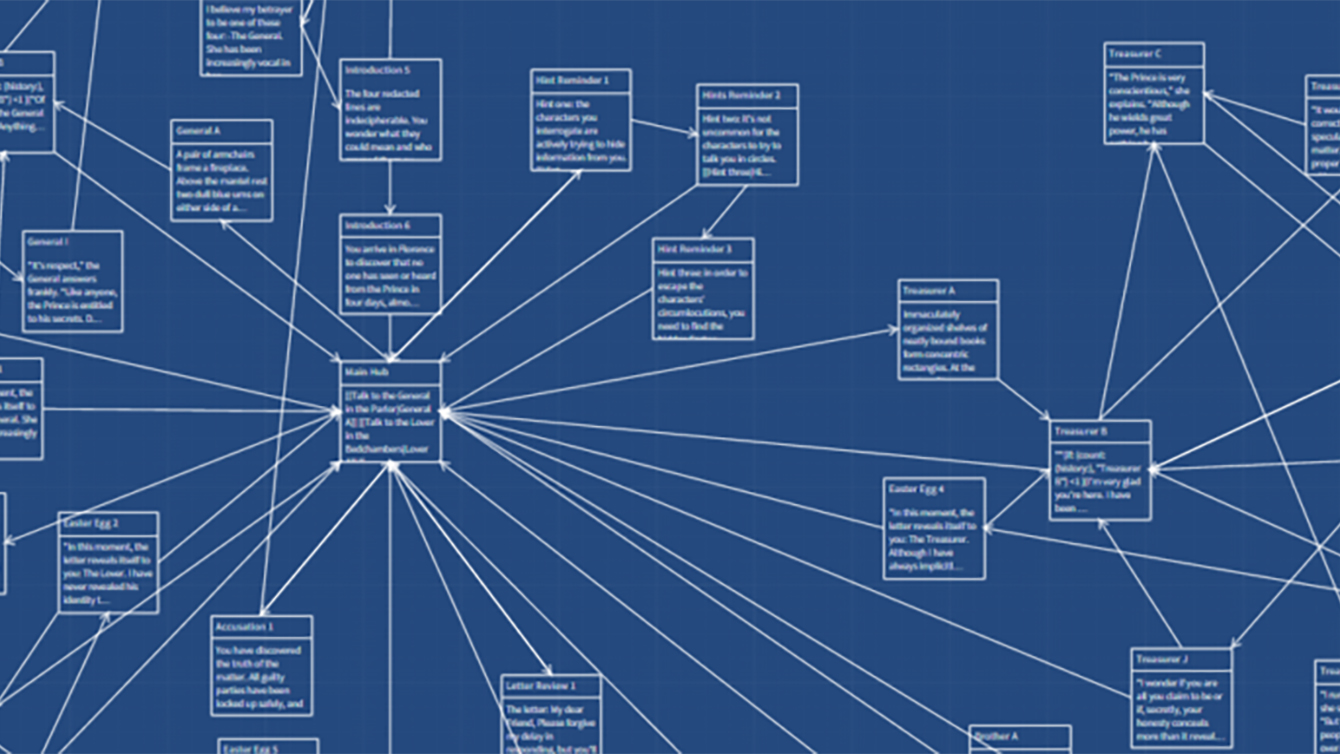

Our collaborative process in creating this text involved web-based documents on which we drafted and revised the text’s arc. The text branched off into four chapters, each principally authored by an individual group member, and everyone’s work was revised in the web-based document by peers. After all the chapters were written and the ending co-authored, the text was coded into Twine, an open-source tool for creating interactive fiction. In Twine the rooms were mapped out [see Figure 1 above], and variables were encoded to determine which pathways would be open to the player under certain conditions. Story progression was designed to be dependent on the player’s discovery of four Easter Eggs. These partially hidden pieces of information all reveal something about the story, but despite such revelations, basic details about the story are intentionally withheld. The text ends when the player becomes trapped in a ring of four rooms that verbally promise to reveal the final meaning, but in the player’s frustrated attempt to progress past them, they never deliver on that promise.

Once we had an initial build of the text, we each playtested it and asked any classmates, partners, and family members patient and kind enough to test the game for their feedback. Based on early playtesting results, we added a hint system to the game’s Easter Eggs and another system for keeping track of an in-game document as its contents become revealed. The current version also incorporates instructor feedback and corrects some mechanical and grammatical flubs. Thank you to everyone who has contributed to this text, and thank you to Dr. Goldberg for the opportunity to work on a creative text as a way of responding to a highly stimulating course.

We hope you enjoy Prince of Florence; if instead you find it frustrating, then we hope we have captured the practice of deception.

Ben Cox

Anirban Gupta-Nigam

Matt Knutson

Diren Valayden

Melissa Wrapp

Please send any bug reports to mknutso1 (at) uci dot edu – thank you!

View the project at http://princeofflorence.uchri.org.