Attuning to the Politics and Poetics of Seaweed in the Hebrides

by

“Holding Sway: Seaweeds and the Politics of Form” is a series of photo essays that channels a visual curiosity about seaweeds with considerations of militarization, gender, Indigenous sovereignty, extractive regimes, and climate change. Foundry guest editors Melody Jue and Maya Weeks invited participants to create or curate images that literally and figuratively “hold sway” in two senses: capturing the attention of an audience, or conveying a relationship of being in touch with seaweeds by holding their swaying botanical forms.

“Learning to attune to these invisible histories requires slowing down and tuning in to different visual and temporal registers—and looking for how the past saturates the present. Seaweeds have stories to tell, and the notion of attunement suggests a willingness to let these stories inform and transform an experience of a place.”

It’s the start of winter, and I have arrived by ferry to Tiree, a small island in the Scottish Hebrides. By now, the tourists have left, and the two cafes on the island have closed for the season. At least the only food shop on the island remains open; I am thankful I will not need to live on seaweed alone. On disembarking the ferry, I feel the wind intensifying. I immediately sense I have arrived somewhere beautiful and bleak in equal measures.

To the west of Tiree are two thousand miles of rolling ocean; the next landfall is North America. The island I find myself on is mostly flat, there are very few hills and no trees to speak of. In Gallic, the island is known as tìr bàrr fo thuinn, “the island whose top lies below the waves,” a name that conjures the image of a submerged land, made as much of water as it is of solid ground. The ocean around the Hebrides is home to vast kelp forests and many other species of seaweed. This plenitude once fuelled the island’s kelp industry, filling the pockets of the estate owners who benefited from this valuable trade. The brutal weather that the island experiences first makes landfall on the west of the island, coming directly off the Atlantic. It is here that I am staying, not far from the foundations of the old seaweed factory in Middleton. My abode is a traditional crofters’ cottage; I feel grateful for the thick stonewalls, small windows, and the traditional thatched roof that protect me from the elements. In the 18th century, it was in structures like these that not only the permanent inhabitants of Tiree lived, but also many of the seasonal workers who came to harvest seaweed.

Like many of those who journeyed to Tiree by boat, I have come in search of seaweed. I intend to use my time here to attune to the politics and poetics of seaweed—to turn my attention to the material history of seaweed harvesting and kelp production that took place on the island more than two hundred years ago. It is a material history that tends to be invisible, leaving little trace in the landscape of the difficult task of cutting, drying, and transporting the seaweed that so many workers carried out. Learning to attune to these invisible histories requires slowing down and tuning in to different visual and temporal registers—and looking for how the past saturates the present. Seaweeds have stories to tell, and the notion of attunement suggests a willingness to let these stories inform and transform an experience of a place. In my practice of attuning, I walk the shorelines around the small island, noticing how different species of seaweed populate the coastlines—from the large remnants of kelp forest broken and washed up on the sand to the west, to the colonies of bladderwrack covering rocky outcrops in more sheltered spots. On this island, some two hundred years later, I too become a seaweed gatherer, searching out phytochemicals contained in these ancient algae—chemicals that I will draw on to make experimental photographic images, imprints, and traces of the seaweed. I think of these images not as representing this island’s history but as traces inscribed with my desire to be transformed as I come to know the seaweed on a chemical and material level, enacted through the slow and material process of image-making.

A material history of seaweed

Seaweed and Tiree have a tangled relationship, bringing fortune and destitution to those involved in the kelp industry in the Hebrides at the end of the eighteenth century. During this period, many travelled to Tiree looking for employment when seaweed was recognised as a valuable resource in the chemical industry, particularly in producing glass and soap. From the 1750s, large amounts of seaweed were harvested, burnt, and processed on the island until a sudden decline in value in the 1820s, leading to disastrous consequences for those who relied on kelping, as it was known. Kelp is a species of brown seaweed; however, in the context of the kelp industry in the Hebrides, “kelp” refers to a finished product, an industrial alkali taking the form of a hard crystalline mass derived from the drying and firing of several kinds of seaweed.

At the height of the kelp industry, workers waded through the sea and gathered seaweed as it washed up on the shoreline—often carrying it over long distances across the rough ground, before it was burnt in pits to yield an alkali extract known as sodium carbonate (also referred to as soda ash), which was used in detergents and to make glass. It was a lucrative business; for a time, seaweed transformed the human settlement and fortunes of the Hebrides. It was a labour-intensive industry that brought people from all over Scotland and beyond for the available work. Yet, like the tide, markets turned, and by the mid-1820s, sodium carbonate was found to be more cost-effective if extracted in other ways. The result was the economic collapse of an industry that had provided employment and homes for thousands of people in the Hebrides. The landlords of the crofts (farms) where the workers lived couldn’t sustain the fall in income, and many ended up clearing the lands as large tracts were turned over to livestock grazing. It was catastrophic for the workers and islanders of the Hebrides, resulting in forced emigration in a brutal process that contributed to the Highland Clearances, driving tens of thousands of people from their homes.1 However, the kelp industry, on a smaller scale, did return to Tiree for a while during the nineteenth century when it was discovered that iodine could be extracted from seaweed.2

Practices of attunement in the Hebrides

The chemicals derived from seaweed saturate the history of photochemistry.3 From Daguerre’s use of iodine fumes to generate photosensitive surfaces in 1839, to the inclusion of sodium carbonate as an active ingredient in many aspects of photochemistry used today. As subject matter, Anna Atkins applied the first principles of photography to seaweed in the cyanotypes she produced in 1843. As I wade through the sea and walk along the shoreline gathering the seaweed washed up on the shore, I think about the seaweed gatherers of two hundred years ago. I feel the icy water and the biting wind and rain against my skin. My city hands are already raw from submerging them in the ocean and untangling pieces of seaweed found on the shore that I will use in my photochemical experiments.

I also seek the chemistry of seaweed—sodium carbonate, to be exact. I have found through experience this compound to be an active ingredient in a photochemical process I use. My method is experimental and a little alchemical; its basis is in photography; however, my method departs from traditional understandings of photography which depends on producing images by the transmission of light. Instead, this practice, which I call Para-photo-mancy, works with the chemistry of plants and algae to create something akin to photographic images.4

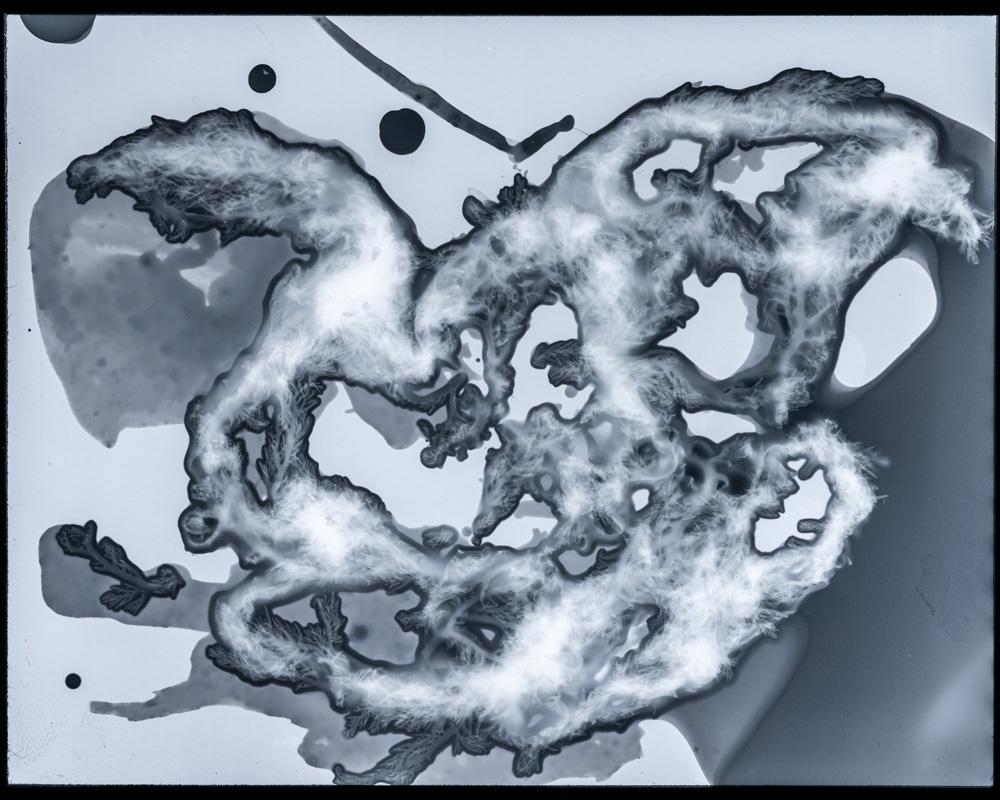

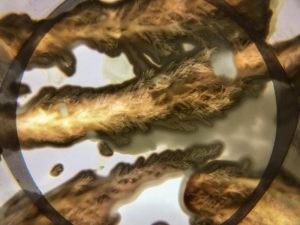

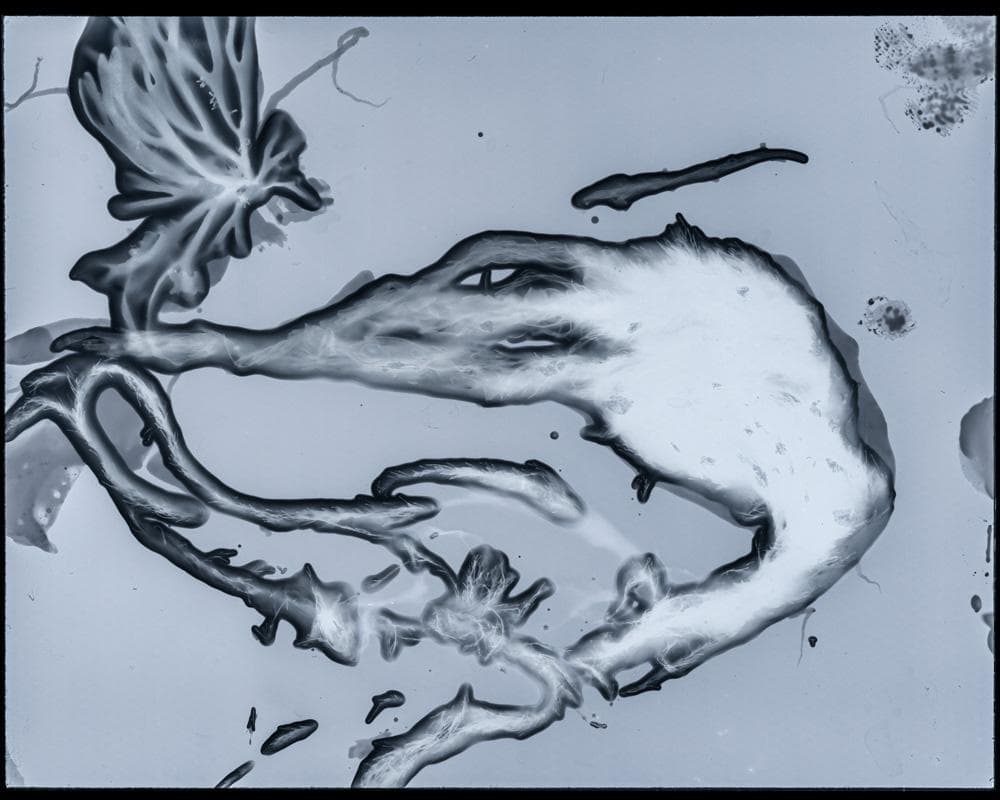

In this practice of Para-photo-mancy, I use sheets of photographic film and fix them by traditional photochemical methods; however, apart from these two aspects, there is little typically associated with photography. The images that emerge from the process are a result of a material encounter that takes place when the phenols contained in plants and algae and the silver halide crystals contained in the photographic film are brought into physical contact with each other. The images generated are not representational in the way we think of a photographic image depicting or showing something to human eyes that once sat in front of a lens. However, these images are representational in the way they record and mediate a process that has taken place in a particular environment involving various sensing bodies, in this case, seaweed, saltwater, and me, to name just a few.

Each day on Tiree, I collect seawater and samples of seaweed that I find washed up on the rocks and shoreline. Taking these back to the crofter’s cottage where I am staying—next to where the seaweed factory once stood—I set out my tools to prepare the seaweed. I soak the samples in a bath of seawater and ascorbic acid. It’s a combination that initiates an alchemic cocktail of alkaloids and acids, much like traditional photochemical developers’ work. Later, I will carefully place pieces of saturated seaweed onto the sensitised sheets of photographic film. The interaction of chemicals works as a photographic developer producing images or impressions on the sheets of film without the need for light. What emerges is always a surprise as the interaction depends on the chemical reactions taking place on a molecular level between the phenols—a compound produced by plants and algae—in the seaweed and the silver halide crystals in the photographic emulsion. It works on a formula based on the chemical force of attractions and repulsions: a shifting relationship between acid and alkali. Para-photo-mancy attempts to harness the material properties of organic matter to bring about an image where the seaweed writes itself onto a photographic surface.

The practice of attuning to the politics and poetics of seaweed undertaken while making these strange (non)photo-graphic images turns my attention to current issues concerning the extensive kelp forests in the Hebrides. There is a renewed interest in seaweed harvesting in the region. If plans go ahead, it will not be harvested by hand like the seaweed gatherers of two hundred years ago. It will be industrial-scale extraction involving mechanical dredging equipment that will far outstrip the gathering that took place by hand at the end of the 18th century. If this happens, it has the power to impact the region’s biodiversity and potentially cause coastal erosion to many of the islands in the Scottish Hebrides.

Apart from the scale and speed of extraction planned, perhaps there is another significant difference from the way seaweed was harvested all those years ago in the Hebrides. The earlier practice of “kelping”—and I suggest we can refer to this as a practice, for it was a craft that involved trial and error, and learning by experience—relied on attuning to seaweed: seaweed species, the seasons, the weather, and the low spring tides that would bring the “right” seaweed to shore, enabling gathering to take place more easily. It was also a practice of attuning that had to work in harmony with the complex ecosystem of the region, taking into account the ebb and flow of the ocean, the availability of a workforce, the scarcity of food that the sea had to offer, as well as the markets’ demand for soda ash. When industrial-scale extraction of seaweed is envisioned for the Hebrides—propelled by the global interest in how seaweed can be used as a biofuel and in bioremediation processes—one has to wonder if such practices of attunement will be part of future seaweed harvesting.

This photo essay is part of the Holding Sway: Seaweeds and the Politics of Form series, funded by UCHRI’s Recasting the Humanities: Foundry Guest Editorship grant.

Notes

- For the history and context of The Highland Clearances, see Eric Richards, History of the Highland Clearances: Agrarian Transformation and the Evictions.

- For more on the histories of Tiree’s seaweed industries, see An Iodhlann and Discover Tiree.

- The historical relationship between seaweed and photography, in the context of saturation, is expanded by Melody Jue in “The Media of Seaweed: Between Kelp Forest and Archive.”

- I write about the practice of Para-photo-mancy in “Photochemical Alchemy.” Para-photo-mancy is based on the phytogram method, a technique first developed by artist and filmmaker Karel Doing, who makes experimental films and expanded cinema.