Coastline Exposure: Staying with the Wrack Zone

by

“Holding Sway: Seaweeds and the Politics of Form” is a series of photo essays that channels a visual curiosity about seaweeds with considerations of militarization, gender, Indigenous sovereignty, extractive regimes, and climate change. Foundry guest editors Melody Jue and Maya Weeks invited participants to create or curate images that literally and figuratively “hold sway” in two senses: capturing the attention of an audience, or conveying a relationship of being in touch with seaweeds by holding their swaying botanical forms.

“Yet what is waste and wrack to some is food, housing and habitat, materials for creativity for a few, and the raw conditions for life on earth for the many. A border zone of human and nonhuman territorial claims, and a contact zone of peoples and many older species, the wrack zone sits with the changes, stays with the trouble.”

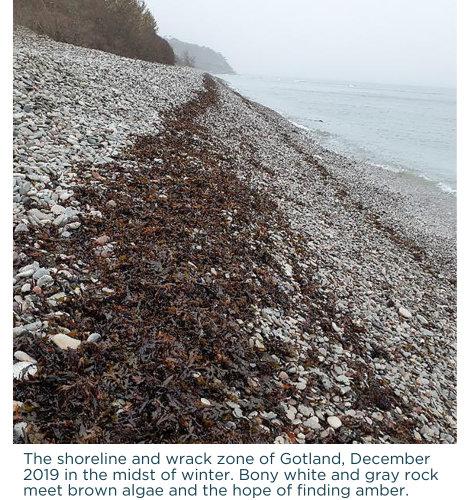

The wrack is called “släke” here on the eastern side of Sweden, a local word for the washed ashore seaweeds. Släke is pulled away by the sheer force of the waves to rot on the pebbles and beaches. The old farmers of Gotland took the släke to their stony and meagre crop fields, used it as a soil fertilizer. Gotland is a hardy limestone island, strategically located in the territorial waters of the Baltic Sea. It is so rich in fossils and lithic deposits from the planet’s previous ancient mass species extinction event billions of years ago that naturalists and geologists of yore even once named the Silurian period Gotlandium. During the Silurian, the island of Gotland was positioned closer to the equator and covered by a sea called the Baltic Basin. Gotland’s sedimentary rock formed here, making Gotland a visible site of layers of deep time matter, rocky outcrops and slow—very slow—exposure. Pebbles and wrack amass, hiding the occasional treasures of bright orange, ancient amber. If you are lucky to find one, the amber might encase a long-dead insect. Much of Gotland acts like an archive in that sense; no wonder naturalists, geologists, historians, and heritage researchers thrive here. The wrack zone also archives more contemporary matters, like nylon fishing gear, tourists’ lost flip flops, and more minute plastic traces of present consumer life. This plastic matter, like all the marine waste, accumulates in the wrack zone. They don’t rot, metabolize, or disappear at the same rate as other organic matter on the beach. Environmental time philosophers Michelle Bastian and Thom von Dooren called the marine accumulations of plastic debris the powerful “new immortals” of our time.

The wrack is called “släke” here on the eastern side of Sweden, a local word for the washed ashore seaweeds. Släke is pulled away by the sheer force of the waves to rot on the pebbles and beaches. The old farmers of Gotland took the släke to their stony and meagre crop fields, used it as a soil fertilizer. Gotland is a hardy limestone island, strategically located in the territorial waters of the Baltic Sea. It is so rich in fossils and lithic deposits from the planet’s previous ancient mass species extinction event billions of years ago that naturalists and geologists of yore even once named the Silurian period Gotlandium. During the Silurian, the island of Gotland was positioned closer to the equator and covered by a sea called the Baltic Basin. Gotland’s sedimentary rock formed here, making Gotland a visible site of layers of deep time matter, rocky outcrops and slow—very slow—exposure. Pebbles and wrack amass, hiding the occasional treasures of bright orange, ancient amber. If you are lucky to find one, the amber might encase a long-dead insect. Much of Gotland acts like an archive in that sense; no wonder naturalists, geologists, historians, and heritage researchers thrive here. The wrack zone also archives more contemporary matters, like nylon fishing gear, tourists’ lost flip flops, and more minute plastic traces of present consumer life. This plastic matter, like all the marine waste, accumulates in the wrack zone. They don’t rot, metabolize, or disappear at the same rate as other organic matter on the beach. Environmental time philosophers Michelle Bastian and Thom von Dooren called the marine accumulations of plastic debris the powerful “new immortals” of our time.

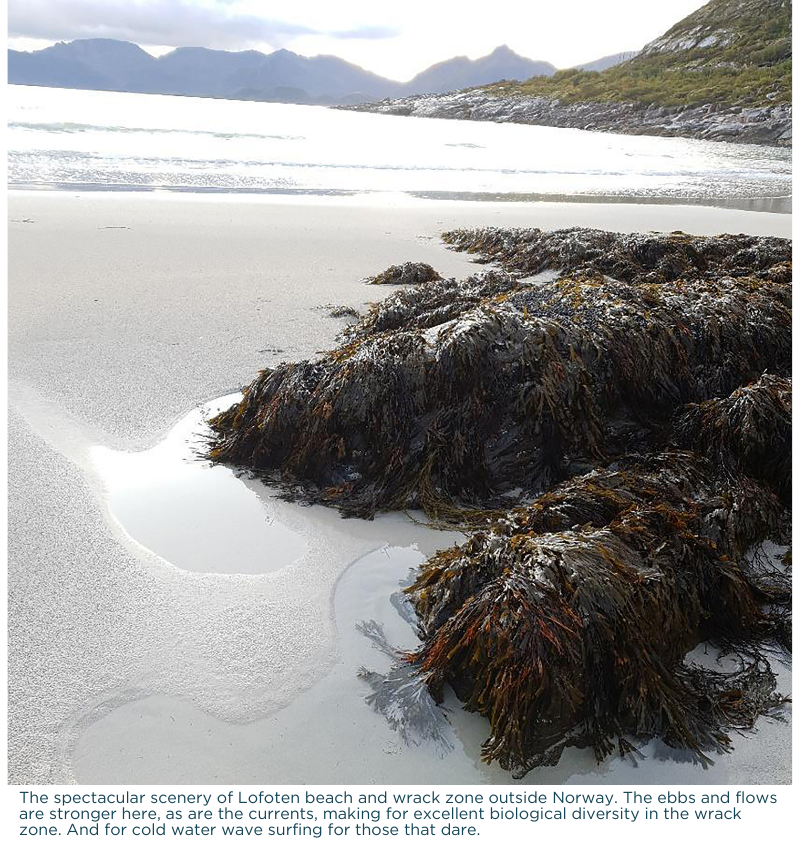

The wrack zone is a particular coastal feature where washed-up debris from the sea amasses. Rotting seagrass, waves, ebbs and flows, shells, plastics, pebbles, kelp, junk, and even washed-up military waste like sea mines and dumped canisters of mustard gas make for a strange multispecies community along the Scandinavian coastlines. Now, the warming ocean waters of climate change bring new kinds of exposures. Biodiversity loss and oceanic degradation demand a new kind of attention to the edges of the sea, to shorelines and to what the sea can take.

Starting from the premise that the sea may be seen as a material archive of matter and memory, Gotland is an intense site of historical territorialism. Here thrives Viking lore, medieval city ruins, and heritage from the Swedish Empire, when Sweden included Finland and Norway and was a major European power of the 17th and 18th centuries, with control of the whole Baltic region, far away shipping, and the slave trade. Less celebrated—and hardly known at all—are the historical dumping practices outside Gotland, at sea, of massive amounts of military leftovers from the First and Second World Wars. Mass-dumping of military waste in the Baltic Sea was, in the 1950s and 1960s, a gesture of farewell to arms. Now they float ashore while Russian attacks on nearby Ukrainian forests, cities, lands and sea basins create a new devastating military record.

“The wrack zone enacts the all too human impact of a whole ecology of marine resources transformed into food, habitat, and energy for a myriad of coastal species…It invites us to forage, to story its exposures, and to stay with the troubles of life on a blue planet.”

Gotland hosts vulnerable multispecies communities, as this shallow ocean is very poor in biological diversity and is today defined by its eutrophication, a lack of oxygenated water and toxic algae blooms. The blue mussels, tiny crabs, and bladderwracks are notably smaller in size in the Baltic Sea. Bladderwrack forests are receding, often overtaken by green slime algae. Agricultural fertilizers from several industrialized nations seep straight into this inland sea, leaving the sea bed deprived of oxygen and creating “dead zones” at the bottom of the Baltic basin. The geological dent in the seabed just outside the island, called the Gotland Deep, was also the intended destination for tons and tons of military waste after the two world wars. The massive dumping of weapons in the sea was intended as a farewell to arms, a gesture of future peace to come. Munitions, sea mines, and slowly-corroding canisters of arsenic-laced mustard gas float ashore or get stuck in the nets of local fishermen. The beautiful and harsh wrack zone of Gotland is the site of multiple seaside exposures and violent encounters over time and place. Old Viking and medieval territorialism, the celebrated heritage of Gotland, meet the storied exposures of industrial worlds at war, with renewed military presence, Russian territorialism, and intensification of climate change along the Baltic coast lines. The bladderwracks bear witness to it all over the aeons of time.

The Baltic Sea bed is also covered in a network of electronic cables and gas pipes, forming a submerged infrastructure that connects the contemporary societies of Norway, Denmark, Germany, Poland, Lithuania, Estonia, Latvia, Sweden, Finland, and Russia with the rest of the world. The damages from the recently exploded pipelines of fossil fuel (methane gas) from Russia are still uncharted. Surely, this was not what the sea ecology needed.

The Baltic Sea bed is also covered in a network of electronic cables and gas pipes, forming a submerged infrastructure that connects the contemporary societies of Norway, Denmark, Germany, Poland, Lithuania, Estonia, Latvia, Sweden, Finland, and Russia with the rest of the world. The damages from the recently exploded pipelines of fossil fuel (methane gas) from Russia are still uncharted. Surely, this was not what the sea ecology needed.

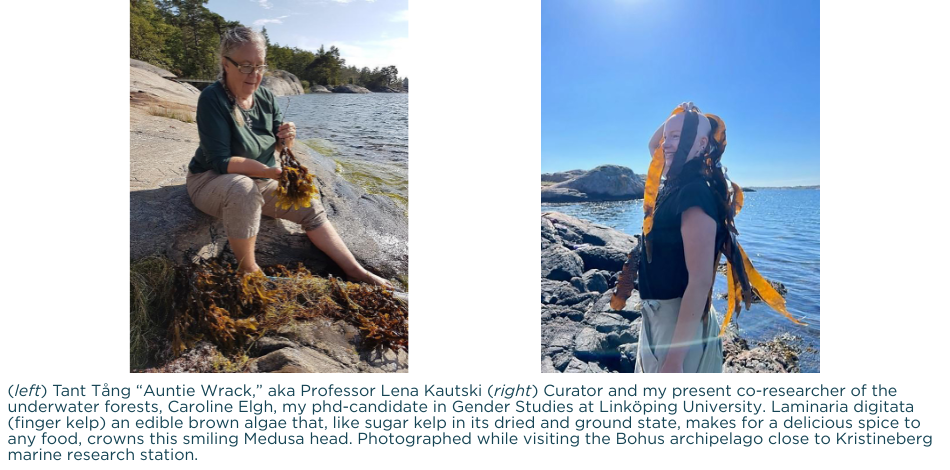

Tant Tång “Auntie Wrack,” aka Professor Lena Kautski, is a pioneering, now retired, marine biologist of the bladderwracks of the Baltic Sea. She never gets tired of telling the bladderwrack stories to visitors of her lab, of the climate threats to its existence, and of the romantic midsummer full-moon conditions needed at sea for it to spawn. Following this, some of my artistic research friends invented a midsummer ritual for scrubbing shoreline rocks clean of green slick, so that the germinating bladderwrack could find a hold.

On the other side, the west coast of Sweden (or the “best coast,” as we called it when I was a kid), the geology of the coastline is harsher and less green. The granite rocks are flattened and smoothed by the heavy glacial layer that disappeared ten thousand years ago to form the much saltier west sea archipelago of Bohuslän.

Kristineberg, the marine biological research centre, is beautifully situated in proximity to Gullmarsfjorden’s species-rich marine ecosystem. Not many sea miles away is Sweden’s only underwater nature reserve, the Koster Sea, famous for its northern coral reef. The focus of Kristineberg as a historical site of marine science has recently changed to “accelerate the transition to a sustainable blue economy.” Entrepreneurs, researchers, and startup companies of seaweed farming gather here. Kelps, especially sugar kelp, and other brown or green algae, sea cucumbers, and tunicates are here exposed and explored as future food. The fjord outside also harbours deliberately sunken war ships, filled with military waste, munition, and chemical warfare agents laced with arsenic so as to remain in liquid or gas form in the cold waters. It is funny that in my childhood, fishermen’s stories of the hard life at sea never even mentioned this. But few, if any, of my grandfather’s relatives are fishermen anymore, there is simply not enough fish to catch. The numbers of cod, herring and mackerel, even the shrimp, have dwindled too fast—even as the fishermen cast a wider Atlantic net.

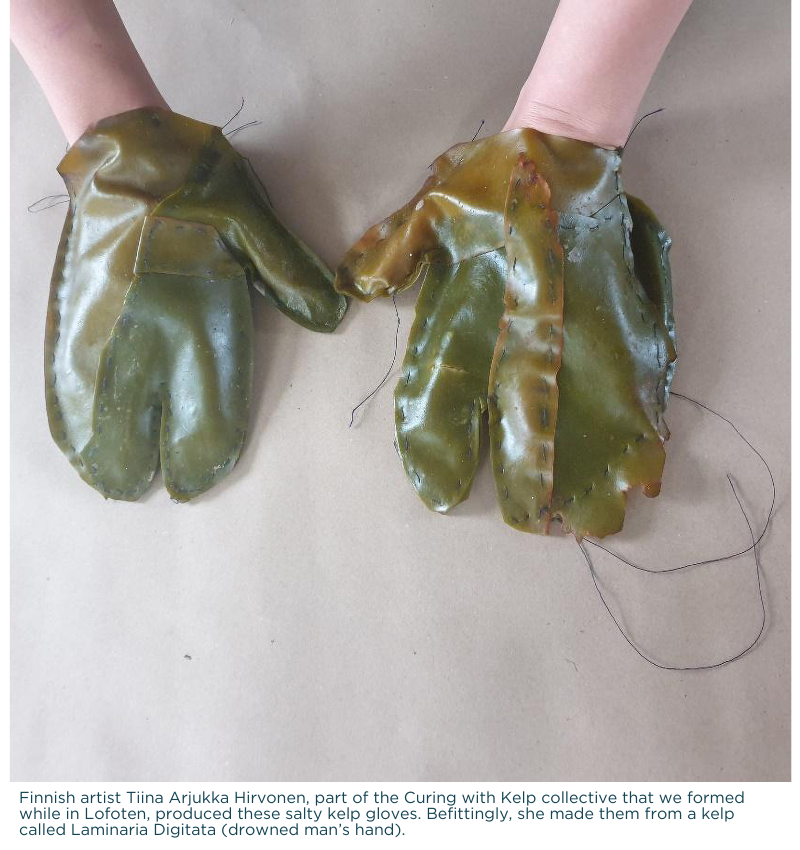

While cold in the arctic sense, the Atlantic waters outside Lofoten are getting warmer too. North of no north, the Lofoten (literally, the Lynx Paw) of islands tap into ancient geology and species developed at the edge of the sea for millions of years to be able to adapt to the harsh climate. Salmon farming and land-based aquaculture has wreaked havoc on its only fishing village, Svolvaer. As stories go, the name of the town is a heritage from the Indigenous Sámi populations that used to live here under the common northern lights. Wilderness hiking across the connected islands of Lofoten is very popular today, and a bit expensive. Dream of my joy of getting here by way of work: my group, The Posthumanities Hub, was invited to support the artistic research workshops of the Kelp Congress and the Lofoten International Art Festival in 2019. My partner and I stayed a few days extra.

Nihil vilior alga. “There is nothing more worthless than washed-up seaweed.” The words are accredited to the Roman poet Virgil 30 BC. It traces the etymology of the very word “algae” to “seaweeds.” Indeed, the wrack zone, the coastal line, features washed-up debris from the sea, and smells distinctly of rotting seagrass, shells, plastics, kelp, and other organic materials. Dictionaries also trace the etymology of “wrack” to associations of ruin and ruination, to wreck and wrecking, to misery, suffering and even, with links to the Old English word “wrake,” to revenge, vengeance, and trouble.

Yet what is waste and wrack to some is food, housing and habitat, and materials for creativity for a few, and the raw conditions for life on earth for the many. A border zone of human and nonhuman territorial claims, and a contact zone of peoples and many older species, the wrack zone sits with the changes, stays with the trouble.

Entangled in a multispecies ethic that does not pivot on a dominant human experience, the wrack zone enacts the all too human impact of a whole ecology of marine resources transformed into food, habitat, and energy for a myriad of coastal species, and for people in contemporary society, too. It invites us to forage, to story its exposures, and to stay with the troubles of life on a blue planet.

This photo essay is part of the Holding Sway: Seaweeds and the Politics of Form series, funded by UCHRI’s Recasting the Humanities: Foundry Guest Editorship grant.