CUT! Community, Immunity, Vulnerability in the Time of Coronavirus

by

Even when the city is locked down, I know we are not an island.

With the coronavirus outbreak in the beginning of 2020, the world seems to have entered an apocalyptic mode of biopolitical insecurity set in zombie fictions. Pandemic anxieties and misinformation pervade; bustling cities are locked down and turned into empty ghost towns. As xenophobia travels across borders with the virus, not only are myriad human bodies from the epicenters equated with the indiscernible virus itself, but they are also surveilled and discriminated in quarantined cities “like Europe in medieval times.” While enmity in China is directed toward people who “fled” from Wuhan before the quarantine, xenophobia changes its name to “Sinophobia,” “anti-Asian racism,” and “yellow peril” across other parts of the world. As bodies repulse bodies, families infect/isolate families, neighbors turn against neighbors, countries close borders, and xenophobic racism runs wild, what we observe in the time of coronavirus is the cutting of relations across all levels.

Dwelling in the wounds opened by the cutting of relations, this essay is an effort to think and race with our time. In a turbulent time when the accumulation of crises strikes a nerve every day, how can we generate new terms to communicate our experience of pains and shared vulnerability? Could the very experience of losing our speech in front of crises become a source of theorization towards a new language of justice we have not yet attained? How can we write and theorize in a creative mode to seize hold of our evanescent affects and memories of the present? If the fortressed world is already a living reality we have to grapple with, where do we start to build a tenuous ethical ground for mourning and being together?

In an effort to come up with a language to dwell in the messy entanglements of apathy and empathy, my departure point is to rethink expulsion as a constitutive element of our lived relationality today and inquire into the self-fortified desires beneath this form of being-together. Attending to the synergic relationship between epidemic, media, relatedness, and biopolitics, I will take “cut/cutting” as a critical concept to diagnose the splintering of relations and highlight emergent forms of togetherness in the time of coronavirus. Whereas a cut in relational terms means truncating one’s tie from another, it could also mean: (1) immunization and amputation from a body in biopolitics, (2) assemblage of fragments in video-making and social media, and (3) an interruption (i.e. “Stop!”) of an ongoing social course. As artist Hito Steyerl foregrounds in her provocative essay, “Cut! Reproduction and Recombination,” cutting is violent, but it also opens up possibilities to assemble and remake the stories of our time. What matters, then, is from which angles, which nodes, and which horizons we are to make cuts into a new story and imagine our being-together in a less fearful, less traumatic way.

The Unbearable Lure of Immunity

How to make sense of pandemic practices of quarantines, travel bans, border closures, and discriminatory attacks ensuing from the coronavirus outbreak? A proposal for understanding the connection between border closure and the coronavirus is to read hostility trans-locally across different forms, including anti-Asian racism in EuroAmerica, Sinophobia among China’s Asia-Pacific neighbors, and animosity within China towards people in and from the epicenters. What we need, I would like to suggest, is not merely a locally-grounded critique but also a general framework that allows us to interrogate how xenophobia travels with the virus symbiotically. It is under this premise that I turn to one biopolitical paradigm that makes relation-cutting desirable: immunity.

Immunity, in its medical and biological meanings, implies the ability of the body to protect itself from an external virus and resist infection by means of its own antibodies. To suppress all threats of contagion, the immune system reacts either by besieging the virus inside the body and outflanking the virus from within, or by chopping off the undesired part of the body in order to keep the rest fit and uncontaminated. As we can trace from the start of the coronavirus outbreak, the strategy of outflanking was clear in China’s desperate efforts to lock down myriad cities to “battle” against the coronavirus, while the strategy of isolation and abandonment was evident in how other parts of the world responded to the epidemic outbreak by immediately putting in place China-related travel restrictions. What is presumed and pursued in all these immunological measures is a stable biopolitical body capable of building fortresses and repulsing threats through preemptive repulsion. In this preemptive repulsion, human (and animal) bodies associable with the disease are projected as imaginable perilous extensions to the virus, turned synonymous with the virus itself, and thus repulsed from the main body of populations.

In “Ghen Cô Vy,” a recent music hit released by Vietnam’s health ministry to advise the public to wash hands, the coronavirus is portrayed as vermin, enemy, devil, and emergent wildfire to be fought against and eradicated.

It is no surprise that under this immunological thinking of a clearly demarcated body versus an unknown virus, a war-time thinking is often deployed in biomedical discourse and is especially visible in China’s total mobilization to fight a “people’s war” against the personified, evil Coronavirus. Displaying a militarized imagination of an entire nation plunged in a total war, this discourse of “people’s war” places political unity and victory over the virus as the highest aim of the national body. Accordingly, familial bonds and social activities, just like all other resources—including food, medical supplies, medical staff, and media control—are entirely absorbed into the maintenance of a stable state. In containing and contracting all persons within the national body as one, the biopolitical state under the attack of the virus desires to “cut” any inconsistent mode of being and keep all parts of its body within controllable boundaries. Such a hyper-protective and contractive response thus gives rise to an inclination towards a form of total governmental control that extends to all realms of civilian life. It is under this circumstance that the quarantined camp becomes an ideal model for immunization. Far from being isolated from the rest of the world, we can say that a quarantined camp like the city of Wuhan or the Diamond Princess cruise ship is, in fact, quite emblematic of our fortified world at this moment.

With this utopian desire for an immunized stable body, however, comes an unbearable cost that persons must be bonded with this national body. When fortification becomes the justification to guard the political body “at all expenses,” individuals become the disposable bearers of stability-oriented policies, top-down media control, and the pains of segregations that mark our time. Tens of thousands of doctors are “dispatched to the battle front,” confronting deaths and helplessness every day. Families are separated from each other for quarantine. After being abandoned by undersupplied hospitals, a number of infected patients could do nothing but return home, leaving a heartrending dilemma for their families to decide whether to isolate them or continue to take care of them under risks. In numerous cases where separated families and individuals could no longer persist to live normally in the ruination of kin severance, splintered cities have turned into necropolises, producing unbearable pains of social death. Stories of these ordinary pains open up a space not only for rethinking the cost of immunological governance, but also for rupturing the fiction of a stable, insurmountable body grounded in this self-guarded biopolitical thinking. True, if we think back to the high morale in the logic of “people’s war,” it is only on the verge of vulnerability and breakdown that high morale and intensified fortification are constantly invoked. The higher the morale, the more the vulnerable body is rendered visible. Instead of being eradicable from the immunized body, then, vulnerability is innate to immunity.

Restorative Montage

Shifting the focus of my analysis from immunity to vulnerability, what I see as a productive move in order to deconstruct the immunological paradigm and engage in pains across borders—a mode of engagement Steven Jackson terms “broken world thinking.” In valuing the limits and fragilities of the world we inhabit, “broken world thinking” attends to a multitude of resilient, creative, and reparative works that serve as the social, psychic, and material fabrics of our mundane living. In this form of thinking, the world, or the body, is always already broken, fragmented, and incomplete, sustained and constituted by resources, reparative work, creative activities, and care infrastructures. Operating on quotidian levels of micro-fixing, small gestures of care are embedded in people’s ordinary lives as modest forms of companionship to help each other pull through moments of disorientation and breakdown. Therefore, during the peak weeks of the coronavirus outbreak in China, precisely at the high point of the spread of misinformation, xenophobia, and infrastructural breakdown there was a simultaneous boom of mutual support on social media: we witnessed not only a month-long robust movement of storytelling and auto-documentation across blogging, vlogging, microblogging, and creative nonfiction writing, but also a flourishing phenomenon of small-scale care works people offered to each other, such as fundraising, transporting medical supplies, patrolling for local neighborhoods, aiding pets, and volunteering to provide listening and mental health counseling.

To take social media seriously as a concrete realm of reality in and through which everyday life takes place, then, leads to my suggestion that this media composite be read as an open-ended site made up of small cuts, patches, and nexuses linking one another to tell kaleidoscopic stories of our time and piecing together islands of broken worlds. Here arises a medial notion of “cut” very different from its biopolitical meaning: rather than truncating ties and establishing borders, a medial cut lives on fragments and performs assemblage. A similar notion exists in the cinematic montage, where a cut separates two shots, but also joins two shots. Like the practice of cutting and piecing a film roll in post-production, the medial cut does not stop at the level of dismemberment, but assembles, sutures, and re-members disarticulated pieces of online postings to construct an alternative space-time for communication and cohabitation.

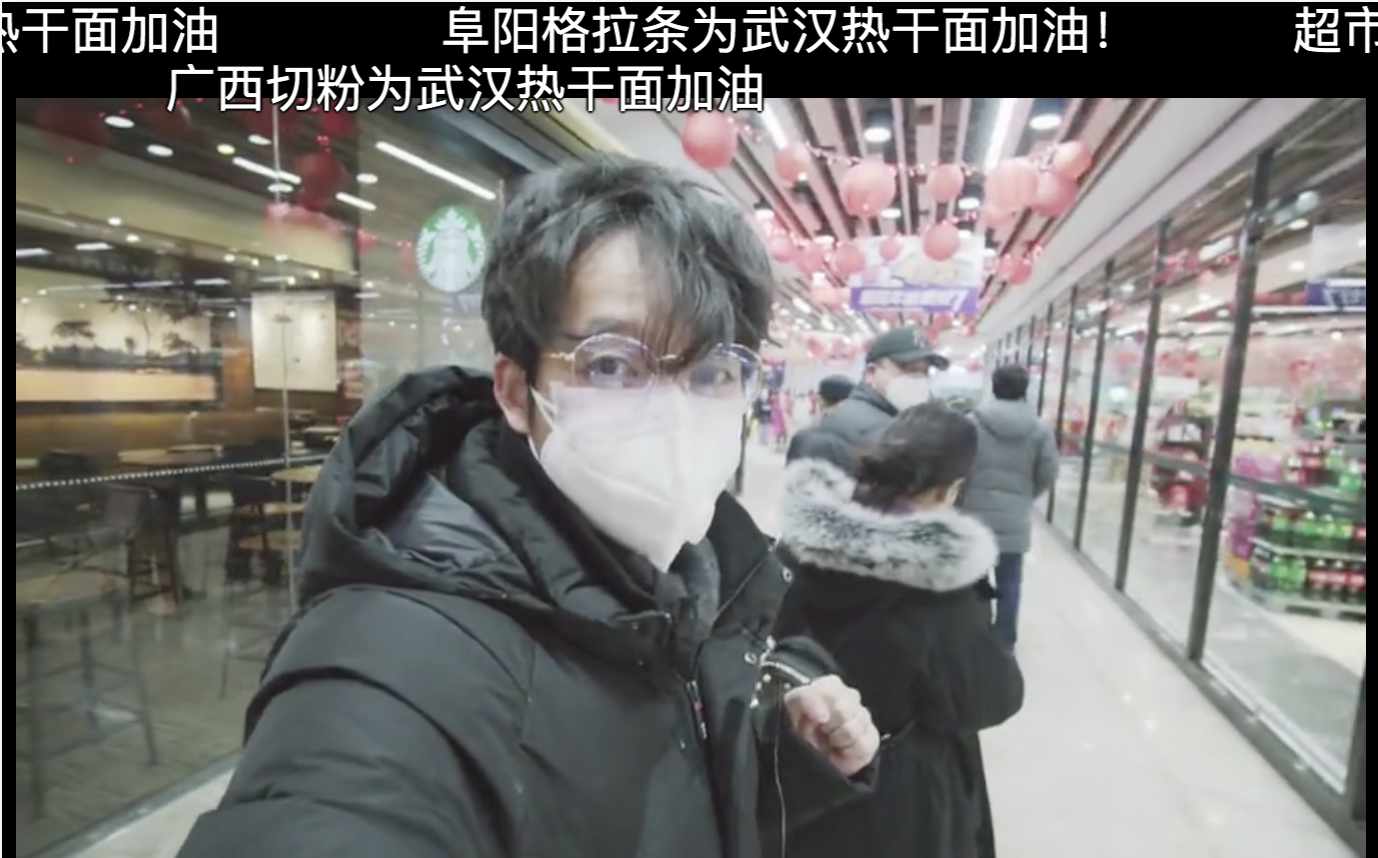

A good example for conceiving the medial cuts is a widely circulated video the vlogger Lin Chen (@Lin Chen Tong Xue) posted on January 24, a day after Wuhan shocked the world by announcing the indefinite quarantine of its population. This vlog is uploaded on Bilibili, a special video sharing website featuring running streams of commentary subtitles superimposed on videos. Within 24 hours after the upload, the video had over 3.4 million views, and 20 days later, the number rose to over 8 million views. Titled “Live Shots from a Wuhan Uploader, 24 Hours after the City’s Lockdown, Food Price, Transportation and Living Status in Wuhan the ‘Empty City,’” this 10-minute video documents a variety of scenes from the first day of the city’s lockdown: empty streets; deserted shopping centers; orderly crowds buying groceries and preparing for a lengthy stay at home; Lin Chen’s phone call with his mother from another town saying he would not be returning home for the Lunar New Year; his conversation with a lighthearted parking lot attendant who could not return home either; shots of shopkeepers, meal delivery men, and parcel delivery men who were keeping the city running; and his poetic narration at the end of the video.

On a plain level, this vlog can be seen as a visual assemblage of various small figures linking up the city and recreating an order of life in a state of emergency. By situating his video-making initiative within a larger network of people as infrastructure, Lin Chen invites us to see video-making (cutting) at this moment of crisis not simply as a construction of on-screen representation, but a genuine mode of social intervention. By no means an epiphenomenon of society, social media—like other forms of infrastructure sustaining the social system—is where interventions are made to mediate real-life relations and remap the ways in which ordinary lives intersect with one another. In so doing, an imagined bond of togetherness is created not only between Lin Chen the vlogger and other residents in his city, but also between them and the audience. As Lin Chen narrates at the end of the vlog:

This city is going through a lot. People are stressed out. But everyone is trying hard to do the right thing. Even when the city is locked down, I know we are not an island— because hundreds of millions of people care about this place. Let’s hang in there for its recuperation. So, here’s wishing everyone a good health. I am Lin Chen. Happy New Year everyone. Let’s hang tight together for the recovery of this city. Till then, we’ll welcome you back to Wuhan, because we’re all embracing this world with tenderness.

Instead of replicating an image of Wuhan as a virus-stricken city crumbling in disaster, Lin Chen emphasizes the work of “care,” “tenderness,” and “doing right things” towards the recuperation of the city. In accentuating collective acts of “waiting for the recovery of this city” and “embracing this world with tenderness,” his narration shows us that, even though quarantines and travel bans are concrete barriers dividing people in and outside the quarantined city, there is still a tenuous common ground—fostered online—for mourning and imagining our being together. Just as Lin Chen says, no one is an island.

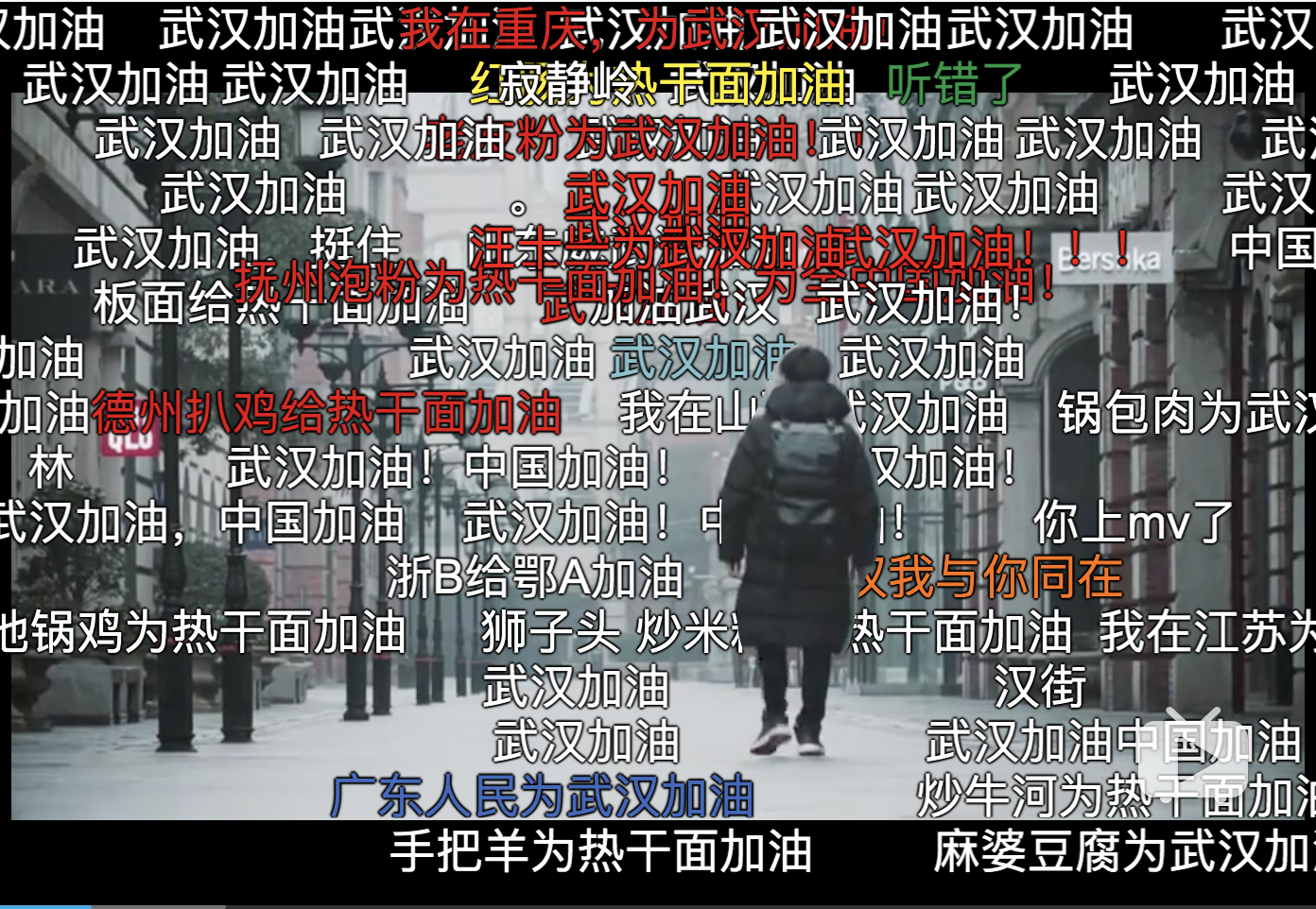

With such an understanding about the vlog, my emphasis concerns the indelible inputs from the audience in co-producing medial cuts and remaking the story of our time. The question here is no longer about the affective documentation within Lin Chen’s vlog, but rather how the media infrastructure itself—the Bilibili platform where he uploaded the vlog—has radically reconfigured modes of relation-making today. As a website allowing “bullet comments” (danmu), or running streams of commentary, to fill the video screen, Bilibili transforms the video screen into a space for viewers to respond not only to the original video but also to each other through their creative play with the style and content of their bullet comments. Through this process, a Bilibili video is at once a chatroom for viewers’ real-time communication in tandem with every frame of the video and a post-viewing archive of their reactions attached to the original video. In Lin Chen’s Bilibili vlog, accordingly, what is presented on the screen is a barrage of 180,000 bullet comments of “Wuhan jiayou” (Wuhan, stay strong) and alike, sometimes even blocking views of the original video. In bringing new layers of blessings and sympathies onto the screen, these bullet comments—each as a small cut jointing one another and reediting the screen—are not merely altering but also co-constituting the video: in myriad commentaries of “Wuhan Stay Strong” laying on top of one another, what arises is a patchwork of affective responses to Lin Chen’s call for togetherness, in the form of an open-ended social relay performed on the video, with the video, via the video.

A frame of Lin Chen’s vlog filled with bullet comments, “Wuhan jiayou (武汉加油),” or “Wuhan, stay strong.” As a creative relay to cheer for Wuhan on the screen, commentators bring up iconic foods from their hometowns to represent themselves and display translocal solidarity with Wuhan. In these lighthearted comments Wuhan is epitomized by its proud hot dry noodles (热干面), and therefore we have comments such as “Mongolian boiled lamb cheers for hot dry noodles,” “Dezhou roast chicken cheers for hot dry noodles,” “(Cantonese) beef chow fun cheers for hot dry noodles” and “(Sichuan) mapo tofu cheers for Wuhan.”

Correspondingly, Lin Chen’s Bilibili vlog, in its social afterlife gained and prolonged through the palimpsestic commentaries on top of the video, is transformed into an unfinished project soliciting viewers’ inscriptions and, hence, an alteration of the video-body. With the nature of co-constitutivity inherent to the structure of Bilibili, Lin Chen’s vlog would not even be considered complete without the inputs/interruptions of his audience. As the viewers’ reception and response is included in the larger process of “video/story making,” every bullet comment is in essence functioning as a cut, a suture, or a flicker into the original body of the vlog, creating additional layers of stories to be told about the vlog and animating an unexpected traffic between the quarantined city and new viewers. In reading, repeating, echoing, and dialoguing with one another via bullet comments, all viewers and commentators of the video are turned into co-creators and participators, bearing witness to the burgeoning sociality of the video.

Cacophonic Silences

Flickers on social media are usually scattered, microscopic, and insignificant, but sometimes they do pop up surprisingly and cluster into transient, visible currents disrupting an ongoing social course. Such is the case of the unexpected mnemonic activism that took place online on February 7, 2020, in remembrance of the passing of Dr. Li Wenliang, an ordinary young doctor who was granted the unbearable title of “whistleblower” for being one of the eight doctors who issued the first warning about the deadly coronavirus. Enormous waves of messages flooded every Chinese speaker’s social media screen, expressing grief for the doctor’s tragic death, outrage over his silencing by the police, and disapproval of the scandalous injustice he had to endure as an ordinary, kind man for telling the truth and reminding others to protect themselves. Elegies, outcries, farewells, and candle signs lit up social media screens. Accompanied by posts of the Les Misérables song “Do You Hear the People Sing?,” Dr. Li’s last words were diffused widely across screens: “There should be more than one voice in a healthy society.” As observed by critics and every Chinese speaker who lived through that day, despite a normalized culture of censorship and self-censorship that runs deep in China today, such a prevalence of grief and outrage across Chinese society had not been seen since 1989.

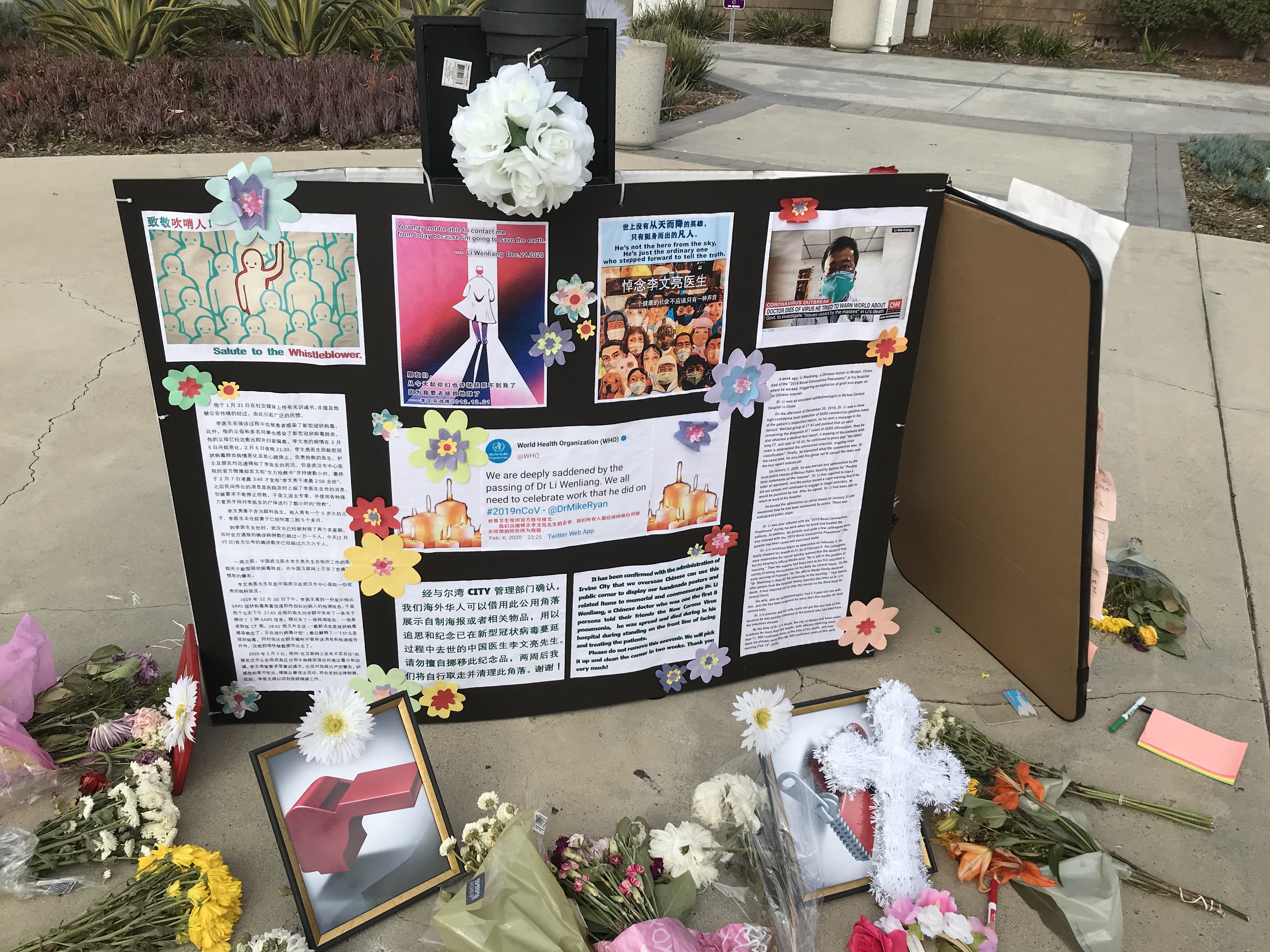

A memorial for Dr. Li Wenliang in front of the Heritage Park Regional Library in Irvine, CA. © Hu Ying

Dr. Li’s death triggered an unusual moment of painful self-reflections on power and conscience, as many Chinese citizens, living tacitly under China’s hardline centralization of power over the past several years, came to realize how any human beings—even those as ordinary as Dr. Li—could be subject to death and injustice when the immunized state grew into a necropolitical apparatus beyond recognition. In a silent post titled “,” small blocks and punctuation marks make up the entire paragraph. The post is written as if its author has already foreseen a future in which any outspoken sympathies for Dr. Li Wenliang will have been censored, lost in translation, and turned into buried taboos as indecipherable as these silent blocks: . What is surprising about/against the languagelessness of this post, however, is its sound translatability among its audience: it went viral, quickly attracting over 100,000 views, and accumulated a barrage of affectively-charged commentaries. In such a special mode of sharing, what touched people so much in this idiosyncratic post was not merely a condition of silence and self-muting with which people in a turbulent political environment could identify, but also an unpronounced radical thesis that, in a time of surveillance and misinformation colliding with the coronavirus outbreak, provides a faithful language for people to remember and share their untranslatable experience of mourning in togetherness, togetherness in mourning. In a further move towards self-imposed silence, the post’s author removed all public comments and closed the commentary board within 24 hours of posting, signifying a fate common to numerous social media posts in China today.1 It is impossible to tell whether the content owner did so out of fear, defiance, or a little of both, but it does reflect this person’s decision that no words other than a sheer blankness would be the best story to tell and to remember Dr. Li Wenliang. Thus, even though a post made up of silent blocks and erased commentaries does not express in words, it marks the condition of human existence symptomatic of our precarious time, and contains ineffably rich layers of grief, anger, fear, defiance, poetry, music, relatedness, and remembrance in silence.

Such a silent and subtle form of togetherness, I would like to suggest, invites us to understand the nature of this unexpected mnemonic activism not necessarily as something revolutionary towards direct resistance, but foremost as a performative assembly of “cacophonic silences” making interventional cuts into the immunized biopolitical body. When silences gather into whispers and turn into cacophonies, these small gestures are not merely signs of delayed, accumulated feelings of lives under the surveillance state, but also carriers of a messianic hope against the continued production of bare lives and social deaths. Instead of being oppositional “threats” to the biopolitical state, then, these small flickers of voices and silences are better understood as generative “interruptions” cutting in and opening up a dialogic space for reflection, critique, and the cultivation of an intersubjective consciousness of each other’s pain. In an immunized time when lives seem too bare to be mourned, an eruption of silence into grief and anger might be the precondition to set us on an alternative political path, while a commitment to remembering and containing these emotional energies eventually leads to the question of reconstructing a resilient civil society capable of self-critique and self-renewal in the long term.

Postscript: An Auto-Ethnographic Note of Writing in the Disjointed Present

As I am typing these words at the end of February, situations of the coronavirus are worsening every day across the world. With strong interventions from the biopolitical state, the disease is reported to be under control in most parts of China. However, in the quarantined cities, after waves of fatigue, scorching anxieties, and mental breakdowns, people are now reaching their limits to coping with stress and suffering. Outside China, the disease has evolved into a global pandemic raging in Japan, South Korea, Iran, and Italy, while exposing structural weakness in other immunological regimes like France and the U.S. With the epidemic situation changing rapidly every day, I am also challenged to think anew and refurbish a living archive, every day.

In the process of painfully searching for words and jumbling together thoughts to capture our time in the coronavirus outbreak, I have a strong sense that my impulse to write stems from an inability to speak, rather than the reverse: I write not because I am free from confusion about our time, but because there are too many epistemic gaps that drive me to navigate through writing. In this regard, writing for me starts from jumbles and aphasia. It is a mode of thinking with our time, and probably more importantly, a mode of living and allowing myself to stumble in the fleetingness of the present. In a manner of running with time to come up with new vocabulary, I constantly wonder: is there a chance that the heartbeat of the present will not disappear in the grand narratives of history, theory, and nation? Is there a chance writing and theorization may bring us closer to our heartbeats rather than muting them or leaving them unattended until they die down? What kind of theory do we need today to comprehend the affect and impulse of our present, and make serious dialogues with these fears and desires?

I think back on Yan Lianke’s metaphor that writers are tasked to invent imaginations and race with the absurdity of reality.

Like creative writing, theorization is an exercise of imagination and storytelling to communicate experience and understanding. In the hope of pursuing a method of storytelling-in-theory and theory-in-storytelling, then, I find myself exposed to a terrain of academic writing I call “documentarization.” What I have in mind is not a form of writing in a documentary style, but like documentary-making, academic writing in moments of precarity is charged with the same sense of urgency, interconnected with other modes of storytelling and tasked with the responsibility to come up with new ways to tell stories in the present tense. Instead of being a speculative reconstruction of the past or a palimpsestic inscription of the present into the past, a writing oriented in the absolute present tense is a form of border-writing that nests our ephemeral affects and contests the limit of our response-ability to the turbulent present.

For a long time in academia, the “present” was a controversial object of inquiry not only because it was confusing enough for people living in it, but also because it did not have a well-layered archive like the “past.” These days, as we are no longer dealing with a deficiency of documents of our present, but with an excess of living archives and their fabrications, it is the fragmented and disjointed nature of the present that constantly invokes our creative translation of our own heartbeats. To that extent, perhaps whatever remains palpably mis/untranslatable in our tumultuous present is what keeps us thinking, writing, and imagining in new terms. As part of a larger relay contesting borders and writing towards interconnectedness, this essay is a critical conversation with our living archives, and itself, too, part of those archives.

- Ironically, in the impermanence of a myriad of online postings today we are seeing the most literal sense of Walter Benjamin’s heuristic Thesis V from On the Concept of History: “The true picture of the past flits by. The past can be seized only as an image which flashes up at the instant when it can be recognized and is never seen again.”