Hamrāhī: Photographing the Assyrian of Iran Community in California’s Central Valley

by

We imagined love and medicine when sharing our stories; we acknowledged our erasure, our trauma, and our journey together. And we invite the viewer into the space they open.

In the Central Valley, where struggle and survival revolve around food production and where scholarly imagination has foregrounded migrant farm laborers, the Assyrian women of Iran in their middle and later ages sustain a different kind of life that remains outside of dominant representations of the Valley. Born to ancestors who survived violence and rebuilt their world after genocide, these Assyrian women carry this intergenerational trauma, memory, and inherited wisdom in their displaced bodies. Their community in the Valley feels forgotten, as younger generations depart and the elderly remain. Illness and death bring about daily erasure. Assimilation, the loss of old networks, fading connections with the homeland, and, at times, internal conflicts place them at the edge of survival. However, these women have quietly and resiliently sought to create a sense of community by nourishing belonging and meaning through everyday acts of remembering, gathering, and caring. The adversities of both the homeland, marked by histories of turmoil and war, and the host land, which has imprinted political tensions on their bodies, have created a protective silence around their stories.

Photo accompaniment is an attempt to attend to these daily erasures. It is an ethical way of engaging, collaborating, and critically exploring trauma, loss, aging, and belonging. Accompaniment, in this practice, aims to create a safe space for healing, enabling the community to relate their stories directly and fearlessly. Also, through the capacity of photography, accompaniment gains an affective and visual dimension, allowing deeper expression of stories in a medium of knowledge that is visual rather than textual. Photo accompaniment is informed in significant ways by George Lipsitz’s theorization of accompaniment in working with marginalized communities.1 It is also built on humanist and feminist traditions of looking that navigate ethical tensions around visibility while cultivating proximity. Photo accompaniment allows us to reclaim creative spaces and foster a sense of connection with these women by sharing a photographic space and witnessing dimensions of their lives that cannot be conveyed in words. Further, this work contributes to our understanding of the Central Valley, not through the lens of agricultural labor, but from the perspective of Assyrian women and their stories, labor, and pain in sustaining their community in a society dominated by male voices. At the same time, the work responds to the female community leaders’ aspirations to ensure their people are seen and acknowledged in the Valley, in scholarship, and beyond.

The camera becomes central because, at one point, you feel the words are unable to carry the weight of what you were experiencing, because what you came to know is beyond the realms of language.

I specifically ground photo accompaniment in epistemic and ethical frameworks of what is known, in the Persian tradition, as practices of Hamrāhī (همراهی, meaning “companionship” or “sharing the journey”) and Hamdeli (همدلی, meaning “shared heart” or “attunement”), where knowing emerges as a process of co-presence, co-feeling, and co-reflection with the community. The prefix ham in both words denotes companionship, togetherness, a broader “we,” and “community.” These notions are loosely translated as “empathy” or “shared feeling,” but, more profoundly, they imply a resonance of hearts and mutual attunement. They provide the affective ground that allows me and these Assyrian women, though belonging to different generations, to feel each other’s presence and pain in unspeakable ways. It has enabled us to turn transgenerational trauma into the ability to collaborate and produce alternative ways of knowing. Therefore, Hamrāhī and Hamdeli become modes of being-with in which our shared history is felt and lived in our relations, shaping how we continue to care for one another. They hold great potential as a new site of knowing, where we can deepen our understanding of how such marginalized, yet resourceful communities sustain themselves despite crisis, and through the intangibility of their women’s daily activism. Such mutual care motivates my desire to know and document the stories and histories of these women, uncovering their aspiration to be seen and recognized. In the words echoed by Anna, Marlene, Flora, and others, “I want people to know who I am,” or as Carmen reminds me: “We need our stories told by one of us.”

When I first met the community in 2023, we were coming out of the isolated world of COVID. Flora was grieving for her brother, who she lost without a final farewell; Janet had just lost her sister and two brothers; Nelie’s husband, and Anna’s brother, Fred, were terminally ill; Rebecca’s father was in hospital nearing the end of his life; Grace’s husband was just diagnosed with cancer; and Carmen was overwhelmed with her mother’s dementia. It was also a time of political polarization in the United States, escalating tensions in Eastern Europe, and the Middle East was entering yet another cycle of conflict. Waking up every day to such news and being unable to concentrate on work became the new norm in my life and in that of many in the community. Our hearts stayed with those we left behind in the homeland. At such moments of crisis, we would offer one another strength of heart and pray together, and this was a way to find solace in one another’s presence.

Even though those events and conversations remained outside the camera’s frame, they affected how I held the camera. I had to navigate tensions, old and new, about visibility. I excluded those who did not want to be seen or have their stories told, even though they were always present in community spaces. My focus, therefore, turned to how bodies come together in such challenging times. I photographed bodies in prayer, bodies laboring together, bodies embracing one another, and bodies gathering to offer comfort. From them, my artistic vision took shape around both the ethical negotiations with the community during the image-making process and the desire to resurface aspects of untold stories that were part of our collective lived experiences and feelings through the choice of color palettes, angles, shadows, and gestures.

As my work with the community evolved, I began thinking about how to create new meaning through the image.

This series of photo accompaniment emerged from years of dwelling with these Assyrian women in such spaces of grief, spaces of trauma, spaces of ruin and loss, of being present, of listening more than anything else, of letting your body be engulfed by others’, letting your body become part of the affective rhythm of community life, of prayers, funerals, care circles and collective labor, and letting your own sorrows become shared pulse that heals your heart, their hearts. Moreover, photo accompaniment enacted community in my practice (as opposed to knowledge extraction practices), turning these images into evidence of how we (the community and I) felt, experienced, and survived displacement together. It is then that you become conscious of stories emerging from those spaces, movements, and bodies. And, the camera magnified them, allowing us to stay with them and meditate on our sense of being. The camera becomes central because, at one point, you feel the words are unable to carry the weight of what you were experiencing, because what you came to know is beyond the realms of language. You have transcended that. You need another medium that encompasses dimensions of your experience, from past to present to future, a means that allows you to imagine your dialogue with the community.

As my work with the community evolved, I began thinking about how to create new meaning through the image. With all the photographs I had taken during my journey with the community, I began overlaying different community images on top of one another, on maps, and on archival materials to grasp aspects of how we have experienced displacement, loss, and trauma, as well as how we have sustained and healed. The aesthetics emerging from the processes of photo accompaniment mediate a new sense of agency that encompasses layers of history, theory, and perspectives of women at their different ages, of the personal, the political, and the collective. These visuals have never been separated from our communal challenges or from our love for one another, but have been at their heart. They illustrate how we inhabit history differently, from our own perspective.

We imagined love and medicine when sharing our stories; we acknowledged our erasure, our trauma, and our journey together. And we invite the viewer into the space they open.

Photo accompaniment 1: Looking together at past worlds…

We look at past worlds in the family albums. They are spaces of presence that intertwine memory with grief, past with present, making the act of “looking” a form of hamdeli that evokes in us a bitter feeling of uprooting.

Photo accompaniment 2: You have left home, but home never leaves you…

You carry home inside you. Even when you are lost in the vastness of the Valley, it takes you to the road, searching for a path that takes you back to familiar places, familiar faces, and familiar hearts.

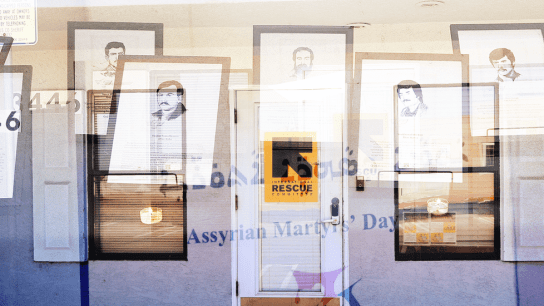

Photo accompaniment 3: My memory from my ancestral village in Urmia, Iran…

In flocks…

Assyrians have abandoned their homes, their villages, their churches

In ruins…

Almond orchards, vineyards, the only spring of the village…

From border to border … they carry the church in their bones,

In foreign lands…

Raising it again … shaking out its light to find each other.

Photo accompaniment 4: We hold us up when our stories fall into silence…

Surprise honorific parties have become community rituals. Rituals of remembrance, to remember how we survive displacement together, how we took pieces of what was left from our broken lives and made a community where we thrive together. Survived and thrived, because we have a community that loves us, that lived with us our darkest days and shared with us our brightest nights.

Photo accompaniment 5: We reimagine the lost history of our villages in Urmia through making Easter Galla…

The rhythms of laboring together to make Galla brings back memories of home, of how mothers would make it, how children would share it, and how the whole village would celebrate Easter together. Galla is not merely any food; it embodies a cultural schema among Assyrians of Urmia, encompassing their ways of bonding and caring for one another whenever destruction is inflicted upon their communities.

Photo accompaniment 6: The community knows my name, and feels my pain…

What is community for you?

“I can’t imagine enduring without my community. When my husband was diagnosed with cancer, and during the two years we suffered, the community was with us. Every day, they would attend to our needs. They were more than a family to me because my sisters live in San Jose. Janet and Pastor Charles would bring Holy Communion to Fred in the hospital because, you know, when you are in the hospital, your morale is low; you lose the spirit and hope, and those visits helped us a lot. The community never left us alone. They prayed for us, cooked for us, visited, and made us laugh after chemotherapy sessions. I couldn’t have borne it without them; it was extremely hard, and I had to work as well. Even after Fred’s passing, they are always with me.“ —Nelie

Photo accompaniment 7: …

Departure from Iran: 1978

Return: Never

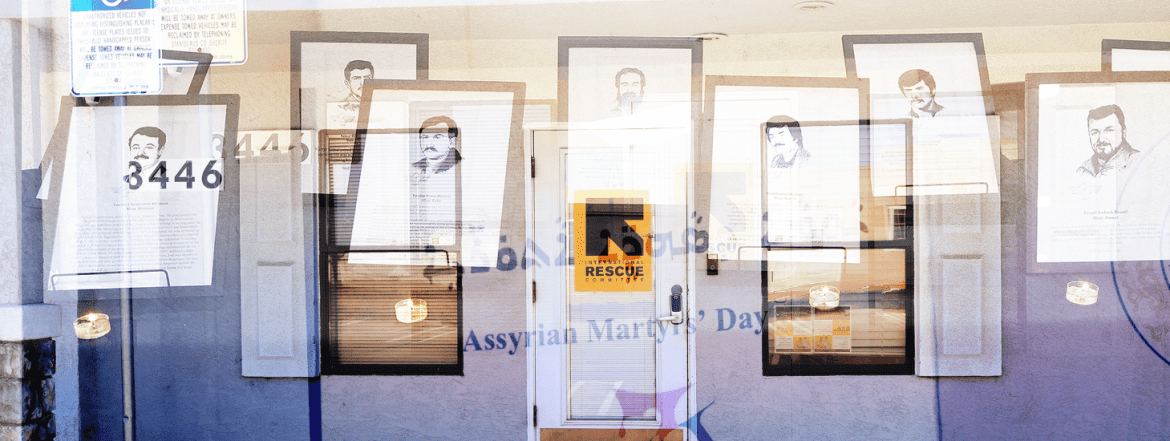

Photo accompaniment 8: Sometimes “RESCUE” is just a word on the door of international offices…

Our history is haunted by thousands of souls whose names, lives, and stories were lost to the atrocities of ethnic cleansing.

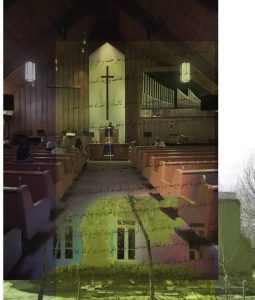

Photo accompaniment 9: We gather fragments whispered at the edge, we turn the pages of men’s memory, seeking the shadows linger unseen by remembering Marlene’s late mother … Sophia Mirza … a genocide survivor…

“I have never seen my grandparents. I know only the names of my grandmothers, Narges and Farangis. I have no photos of them, though, nor do I know anything about them. I just know that my maternal grandfather came to the U.S. as a migrant worker. Then, during the Flight (the forced migration of the Assyrians of Urmia during the 1915 genocide), my mother and her older sister, who was a teenager, were among the masses who walked for kilometers to the Baghdad camp in Iraq. For months, my grandfather had no news of his daughters. He went searching for them in Iraq and found them. I always regret why I never asked my mother about her story.” —Marlene

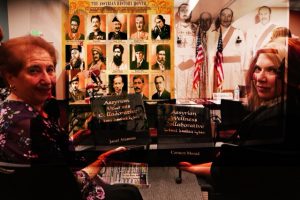

Photo accompaniment 10: We weave our history into the record…

Because we have been holding our community together. We became healers when there was no closure for our displaced parents:

“My mother was always in transition. She never felt this was her real home; her real home was back home. We knew people in our community were suffering from the hardships of migration, yet we remained silent; it was not just my parents. When the Iran-Iraq war happened, many Assyrians fled Iran. We heard horrible stories. They fled on foot. They literally walked to countries and sought refuge. They became refugees. They spent years in refugee camps before they arrived here. We knew trauma existed. We needed to start this conversation about healing, and we did that through the Collaborative, and we repeated it over and over for a decade to normalize it.” —Carmen Morad, community leader

- Barbara Tomlinson and George Lipsitz, Insubordinate Spaces: Improvisation and Accompaniment for Social Justice (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Temple University Press, 2019); Daniel Fischlin, Ajay Heble, and George Lipsitz, The Fierce Urgency of Now: Improvisation, Rights, and the Ethics of Cocreation (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013); George Lipsitz, Footsteps in the Dark: The Hidden Histories of Popular Music (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007).