Inauditas: Listening to the Sound of the Distance

by

“Migration is an orphan that nests outwards.”

“Migrar es una orfandad que anida hacia afuera.”

– Elena Cardona

Inauditas: Tracing the Sound of Migrant Memories in Venezuelan Women Photographers is an exhibition on migrant photography and photography of migration, focusing specifically on Venezuelan migration from 2016 to 2022. Each artist featured in this exhibition challenges the notion of photography that reduces it to the “visual,” while disorganizing a traditional notion of the “audible” that takes away its “auratic” effects, thus reinforcing the experience of photography as one of listening.

This introductory essay for Inauditas includes both English and Spanish text translations.

Listening to the Sound of the Distance (English)

How can we listen to something that no measure can encompass and whose unfathomable, incalculable experience so tangibly contests the possibility of representation? How can we lend a voice to something that will not allow itself to be said, but whose relentless presence cuts through the space of every resonance, sometimes leaving it untouched? The experience of being afar can often be silent—although its silence is clamorous—or can sometimes feel like it is patiently awaiting the arrival of the right word or image to describe it, but it is always overwhelming as it seizes hold of it all. To yearn for everything that is familiar to us, to arrive as newcomers into other lives that render us strangers to ourselves, is to experience a distance whose reach lies encoded in the place described by the unheard of [lo inaudito]: by the sounds that are no longer there and heighten the absence, by the words that now bounce back instead of ringing out, reminding us that space, which we understood to be continuous, is brutally severed by sealed frontiers; by the lack of a language, of an idiom, of a grammar that could tell the story of how the world was shattered by something that should not have happened.

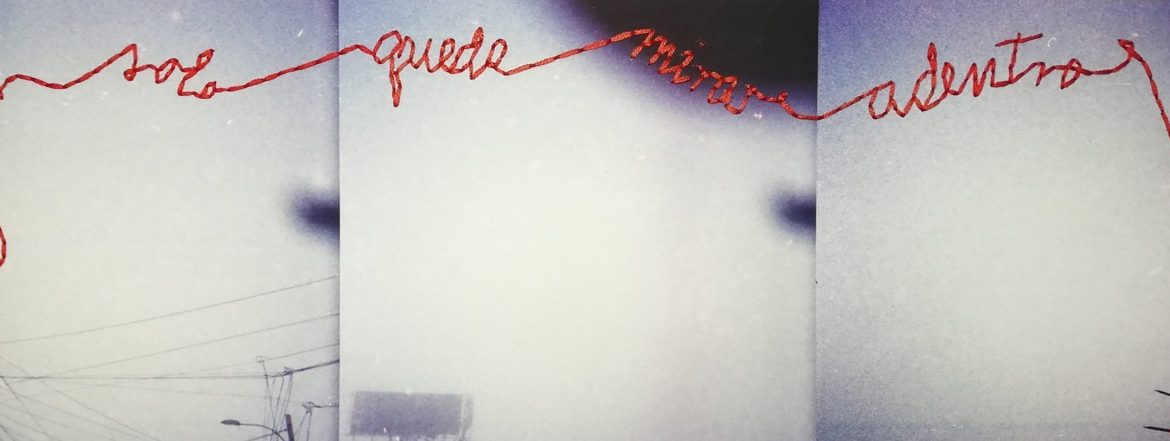

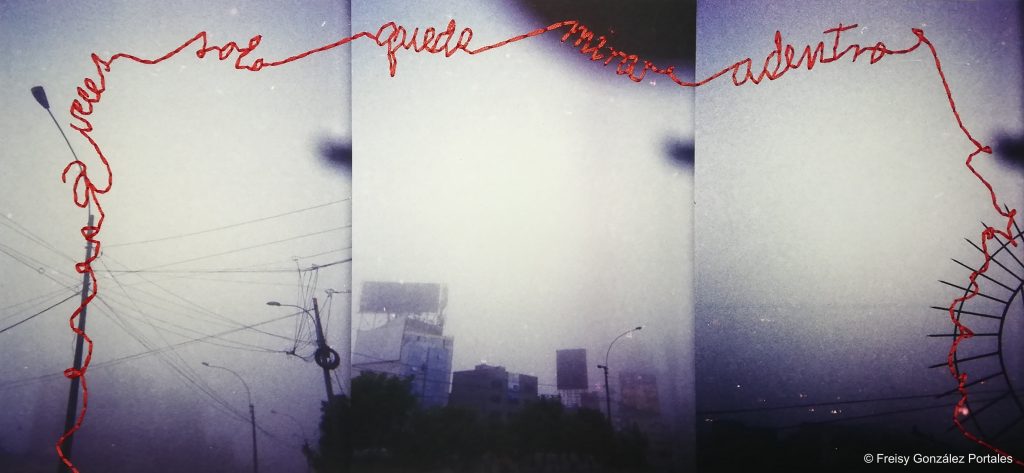

The photographs and videos collected in this exhibition summon us to translate the visible into a space of audibility where, through images, we hear a story that will not allow itself to be collected in words alone; or where the words themselves take the shape of images, “as though making waves,” as Freisy González Portales puts it, so that the image itself is now able to “expand time in words.” Here the distance seems to be something that we experience by listening, as in the verses that title Fabiola Ferrero’s work: the sounds that are no longer there appeal to us through these images, those “(in)audible measures of the distance” that “resonate in another frequency” (to quote Elena Cardona) or that interrupt and traverse the image, as in Diana Rangel Lampe’s videos, where memory breaks into the landscape. It can also split the image in two, as in Verónica Aponte’s photographs, or cause it to speak from within, as in Vilena Figueira’s postcards. Or else, as Wendy Estrella Yannarella explains, it may also occasionally give way to “a burst of pure image” in a form of photomontage that is no longer just a site for testimony, but also a site for emancipation.

This double gesture of giving testimony while also making place for resistance and emancipation runs through the works of these artists. They all find in photography the possibility of conjuring those moments of enduring latency, of getting across boundless spaces marked by the impossibility of return, and of thereby—and ultimately—lending a voice not only to their migrant memories but to the phenomenon of migration itself. In each of these images, and in the testimonies that accompany them, we find the traces of something that is woven and unwoven between them, something that both ties them together and drastically sunders them. Each of them, through an experience that is always unique, calls attention to a phenomenon whose reach and magnitude remain unheard of—because it is unprecedented in the region, because of the outrage that it should (and fails to) provoke, and because of the myriad histories that have remained unheard in the process of its speedy normalization. The migration of persons who have left Venezuela during the past five years in conditions of vulnerability is in fact the greatest displacement crisis in the world after the crisis in Syria, which it far surpasses in numbers (over seven million people have left Venezuela between 2016 and 2022, adding up to 20% of what would be the country’s current population.)

Its magnitude is only one of the features that make this such a difficult event to digest. In their photographs each of these artists reminds us that, beyond these numbers, colossal in themselves, we find the life stories that remain: the altered photo albums in Estrella Yannarella’s Illusorium, which seek to replenish familiar spaces with memories of past spaces forcefully abandoned with no possibility of return; the overlapping temporalities in Aponte’s Hiatus 2002-2020, which shows how the experience of migration can go beyond the temporality of perpetual awaiting and yield to a sense of overcrowded moments that never fully fit into the field of the visible. Similarly, in her photographs Cardona uses chiaroscuro to cut out the landscape with light and shadow and tell the story of its ghostly spectrality; and the seams that run across, tear out, and suture González Portales’s images lead us to experience return as a repetition compulsion.

Ferrero tells us that in I Can’t Hear the Birds we see “the silent, daily struggles,” but also how “amidst the chaos, life always finds a way.” The record of everyday life holds fast to this two-faced violence that we live and deal with in the quotidian. In this exhibition we experience this everydayness from within, in Venezuela as it is now, after the greatest migration in the history of the region; and from without, in the gaze that connects from afar—from the sea depicted in Figueira’s Memory Postcards, which both is and isn’t This Sea That You See, and which “alludes to all the images that have been and will be in the world,” thus bringing together the possibility of memory (inscribed, encrypted in those postcards) and the breach of a future that unfolds with the temporality that is both encapsulated and liberated by capturing the sea. Here, as in Rangel Lampe’s Margarita, the landscape bears the history of its times, and the times of all those histories that, unheard of, are yet to be received.

Curatorial Commentary

The sound of the birds, their song that can no longer be heard; the mother’s voice on a recording; foreign voices; migrant voices; the sounds of the street; silence; the act of listening; all of these are part of a semantic field of sound that is insistently thematized in these photographic projects as part of the mourning process, linked to a double gesture of memory: oblivion (detach) and (un)oblivion (reimagine, reinvent.)

Escuchar el Sonido de la Distancia (Español)

¿Cómo escuchar aquello que rebasa toda medida, y cuya experiencia inabarcable, incalculable, reta de modos tan palpables la posibilidad de su representación? ¿Cómo dar voz a aquello que no se deja decir, pero cuya presencia obsesiva atraviesa, a veces sin alcanzar a tocarlo, el espacio de todo lo sonoro? A menudo silenciosa, aunque calle a gritos, algunas veces paciente en sus modos de esperar la llegada de la palabra o de la imagen acertadas, pero siempre abrumadora en sus maneras de tomárselo todo, la experiencia de estar lejos, de la ausencia de todo aquello que nos es familiar, de la llegada a otras vidas que ahora nos tornan en extrañas para nosotras mismas, es la experiencia de una lejanía cuya distancia queda cifrada en el lugar descrito por lo inaudito: por los sonidos que ya no están y que refuerzan la ausencia; por las palabras que ahora rebotan en lugar de resonar, recordando que el espacio, que creíamos continuo, está cortado de tajo por fronteras infranqueables; por la carencia de un lenguaje, de un idioma, de una gramática que sea capaz de relatar la ruptura del mundo que resulta de aquello que no tendría que haber sucedido.

Es a esto a lo que nos convocan las fotografías y videos reunidos en esta exposición: a traducir lo visible en un espacio de audibilidad en el que escuchamos en las imágenes un relato que no se deja recoger solo en palabras; o en el que las palabras se transforman ellas mismas en imágenes, “como creando ondas,” nos dice Freisy González Portales, para que sea la imagen misma la que logre “expandir el tiempo en palabras.” La escucha aquí, como en los versos que dan título a la obra de Fabiola Ferrero, parece ser la clave de la lejanía: son los sonidos que nos faltan los que nos interpelan desde estas imágenes; esas “(in)audibles medidas de la distancia,” escribe Elena Cardona, que “resuenan en otra frecuencia;” o que interrumpen la imagen y la atraviesan, como en los videos de Diana Rangel Lampe, interviniendo el paisaje con la memoria; cortándolo en dos, como en las fotografías de Verónica Aponte; haciéndolo hablar desde dentro, como en las postales de Vilena Figueira; o “estallar en pura imagen,” como lo describe Wendy Estrella Yannarella, para transformar el fotomontaje ya no solo en lugar del testimonio sino también, como lo dice la artista, de emancipación.

Este gesto doble, el de dar testimonio y ser a la vez lugar de resistencia y emancipación, recorre la obra de todas estas artistas. Cada una encuentra en la fotografía la posibilidad de conjurar los tiempos de una latencia que no termina, de recorrer los espacios inabarcables que marca la imposibilidad del retorno, y de dar voz, con ello, y en última instancia, no solo a sus memorias migrantes sino al fenómeno mismo de la migración. En cada una de estas imágenes, y en los testimonios que las acompañan, se encuentran los rastros de aquello que se teje y desteje de una a la otra, que las ata y a la vez las separa de maneras tajantes, y que cada una de ellas denuncia desde una experiencia, cada vez única, de un fenómeno cuyo alcance y magnitud no dejan de ser inauditos—por lo inédito para la región, por el tipo de indignación que debería ocasionar (y no ocasiona), y por todas las historias que han dejado de ser escuchadas en el proceso de su rápida normalización. La migración de personas que han salido de Venezuela en los últimos cinco años en condiciones de vulnerabilidad constituye la crisis más grande de desplazamiento en el mundo después de la crisis de Siria, a la que supera en números (más de siete millones de personas han salido de Venezuela entre 2016 y 2022, número que equivale a casi el 20% de lo que sería su población actual.)

Lo masivo de este evento es solo uno de los aspectos que lo hacen tan indigerible. Lo que nos cuentan cada una de estas artistas en sus fotografías nos recuerda que, más allá de estos números, ya de por sí descomunales, se encuentran las historias de vida que quedan atrás: los álbumes de fotos intervenidos en Illusorium de Estrella Yannarella, que buscan llenar los espacios familiares con los recuerdos de un pasado cuya espacialidad ha tenido que ser dejada atrás sin posibilidad de retorno; la superposición de temporalidades en Hiatus 2002-2020 de Aponte, que nos habla de cómo, más que una temporalidad siempre en espera, la migración se experimenta, también, como tiempos apiñados que no logran casar del todo en el campo de lo visible. Así sucede también con los claroscuros de las fotografías de Cardona, donde luz y sombra recortan el paisaje de la memoria para relatar su espectralidad fantasmal; o en las costuras que recorren, desgarran y suturan las imágenes de González Portales, en las que el regreso se experimenta como compulsión de repetición.

No Oigo los Pájaros, nos dice Ferrero “muestra las luchas silenciosas de la vida cotidiana, pero también que, en medio del caos, la vida siempre encuentra un camino.” El registro de lo cotidiano insiste en esta doble cara de la violencia que se habita y se tramita desde el interior de la cotidianidad. Una cotidianidad que esta exposición muestra desde adentro, en la Venezuela que queda después de la migración más grande de la historia de la región, y desde afuera, en la mirada que se conecta desde la distancia, desde el mar en las Postales de la Memoria de Figueira, que es y no es ya El Mar Que Ves, y que “alude a todas las imágenes habidas y por haber,” recogiendo con ello la posibilidad de la memoria (inscrita, encriptada en esas postales), pero también la apertura de un futuro que se abre con la temporalidad que la captura del mar encapsula y libera. El paisaje aquí, como en Margarita de Rangel Lampe, carga consigo la historia de sus tiempos, y los tiempos de todas esas historias que, inauditas, están aún a la espera de ser recibidas.

Comentario de las Curadoras

El sonido de los pájaros, su canto que ya no se puede oír; la voz de la madre en una grabación; las voces extranjeras; las voces migrantes; los sonidos de la calle; el silencio; el acto de escuchar; son parte de un campo semántico de lo sonoro que es tematizado insistentemente en estos proyectos fotográficos como parte del proceso de duelo, en vínculo con un doble gesto de la memoria: olvidar (desprender) y desolvidar (reimaginar, reinventar.)

“Inauditas: Tracing the Sound of Migrant Memories in Venezuelan Women Photographers” photo essay series

“Hiatus 2002-2020,” Verónica Aponte

“Measures of the Distance,” Elena Cardona

“Illusorium,” Wendy Estrella Yannarella

“I Can’t Hear the Birds,” Fabiola Ferrero

“This Sea That You See. Memory Postcards,” Vilena Figueira

“Where You Are No Longer Anything + Back to the Blue,” Freisy González Portales

“Margarita,” Diana Rangel Lampe

This series is published in conjunction with the exhibition, Inauditas: Tracing the Sound of Migrant Memories in Venezuelan Women Photographers, curated by María del Rosario Acosta & Elena Cardona, and organized by Eastside Arthouse, from February 11, 2023 through March 4, 2023. Materials in this series were previously published in the Inauditas exhibition catalogue, made possible by the contributions of the following: María del Rosario Acosta López & Elena Cardona (Introductory essay and curatorial commentary texts); Elisa Cardona (video editing and animation); Jaime Cruz (catalogue designer); Lara Boyero Agudo and Gwendolen Pare (copyeditors); Tupac Cruz (translator); Gelimas Chilliprinting, Inc. (Printer).