Memory Histories: I Am Not Your Data

by

Responding to the theme of Care & Repair, UCHRI is republishing select pieces from The Humanities Institute (THI) at UC Santa Cruz faculty series. Together, these scholars from different disciplines meditate on the healing capacities of memory, imagination, and travel to explore their potential for care and repair. To read the essays in their original context, see the THI series on Imagination, Travel, and Memory.

I am not your data, nor am I your vote bank,

I am not your project, or any exotic museum object,

I am not the soul waiting to be harvested,

Nor am I the lab where your theories are tested,

I am not your cannon fodder, or the invisible worker,

or your entertainment at India habitat center,

I am not your field, your crowd, your history,

your help, your guilt, medallions of your victory,

So I draw my own picture, and invent my own grammar,

I make my own tools to fight my own battle,

For me, my people, my world, and my Adivasi self!

Abhay Xaxa 1

So writes Abhay Xaxa, an Adivasi scholar, activist, and artist in an excerpt from a longer poem entitled “I am not your Data” (2011), which remains one of the most militant and poignant tracts of anti-caste aestheticism and politics. Xaxa, member of the Kurukh tribe, born and brought up in Jashpur district, Chattisgarh, India, died tragically of a heart attack in March 2020. A stalwart of Adivasi land reform, Xaxa was first and foremost an intellectual who pushed for radical imaginaries that would combat the data-fication and de-humanization of his Adivasi and Dalit/Bahujan kin.2 If one motif hums through his poem, it is the pressing, almost unbearable awareness of the privations of caste and the unction of history. As if to say, between who we are, and how we are seen, lies an unbridgeable metrics, an archive of algorithmic violence that won’t let us breathe. “So I draw my own picture, and invent my own grammar,” he writes in his limpid litany of refusals, exhorting us, his readers, to imagine vibrant historical vernaculars for Adivasi and Dalit/Bahujan presence.3

For the past decade or so, I have returned often to Xaxa’s trenchant exhortations to think through my own intellectual discomfort with the evidentiary regimes that secure pathways to histories of caste and sexuality, to think about what it means to not be data/fodder for a knowledge supply chain that sees our histories only through lineages of loss, erasure, and paucity. Instead I have turned to the concept of abundance as a heuristic to summon a non-recuperative history of sexuality that embraces presence without return, or the fear of loss. To summon a history of abundance is not to be restored to value, but rather to be set adrift upon more intrepid economies of meaning—sometimes harmonious, sometimes dissonant—that come together to upend genealogies of historical recuperation and representation.

“One’s history was not a place of capture; it was a compositional lexicon of self-making, to be continuously taught, modulated, inhabited, and shed.”

Through my research on a Dalit/Bahujan, devadasi community, the Gomantak Maratha Samaj, I have encountered archives of invention, thriving eco-systems of protest, refusal, and pleasure. The Gomantak Maratha Samaj or the Gomantak Kalavant Samaj, as it is also known, is a historical anomaly and rarity, both in its archival forms and content. The Samaj is a prominent lower-caste devadasi collectivity hailing from colonial Portuguese and British India. Devadasi is a Sanskrit term literally meaning a slave/dasi of a god/master, often falsely read as interchangeable with terms such as courtesan, sex-worker, prostitute. Gomantak speaks to geographical roots in Goa, Maratha. It is both a caste and a regional term, and Samaj translates to both society and collectivity or community. Moving between British and Portuguese India, spread across the border states of Maharashtra, Goa, and Karnataka, the Samaj is the only Devadasi collectivity (with over 50,000 registered members) that has maintained its own continuous archive since its inception in 1927 to today, embracing rather than disavowing its history of caste and sexuality. Its archives in Mumbai and Panaji are accessible and available to all that care to enter (a radical counterintuitive prospect for anyone doing archival research in India), and are full of the minutiae of subaltern life, an efflorescent and heady mélange of fact and fiction, with archival genres that corrupt and stage verifiability in the form of fake birth records, property deeds, and more. A canny archival pragmatism founds these collections where the sheer abundance of the materials is less an organizing than a disorganizing force, shot through by questions of pleasure, practice and subjectivity, agency and ethics.

“I am not your data. I am abundant.”

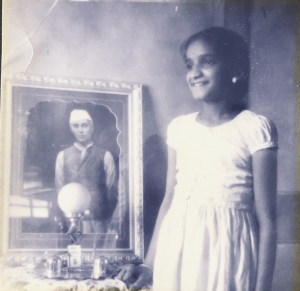

I grew up within the bawdy, colorful, and expansive lower-caste politics of the the Gomantak Maratha Samaj, and it is those familial genealogies that first opened me up to the urgencies of caste, sexuality, and politics. My deliberations thus emanate from those intimacies; they are of them, but not about them. Contravening the protocols of data collection (be they of collectivity, family, caste) was not just a familiar feature of my Samaj life, but a profoundly political matter. One’s history was not a place of capture; it was a compositional lexicon of self-making, to be continuously taught, modulated, inhabited, and shed. To return to Xaxa’s again, I can thus do no better than to tell that story.

I Remember You

I remember you, my mother always tenderly says to my partner Lucy, as she glimpses her across oceans virtual and real every week. My mother is 85, her memory faded and folded into crevices of stories told and untold. In the pixelated landscape of my video screen, Aai’s words linger, a translated rendering of how she manifests absence. “I remember you” is her English condensation of our shared Marathi phrase—mala tujhi aathvan yete—which makes aathvan/memory an act of personal conjuring, a poignant tethering of past and present. I remember you too, Auntie, Lucy always responds, sealing a treasured ritual of long-distance love that sutures affect to a history of memory. To remember is not to grasp a lost form or surrender to the nostalgia of a less violent past (if there ever was one) but more an aspiration of belonging. To fashion a world, or at least a version of a world that brings joy, succor, and the possibility of a reunion.

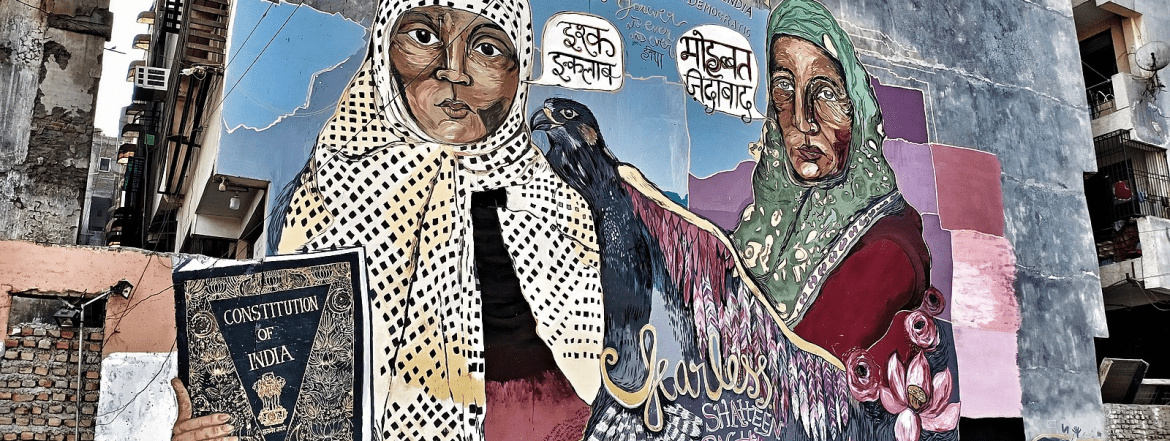

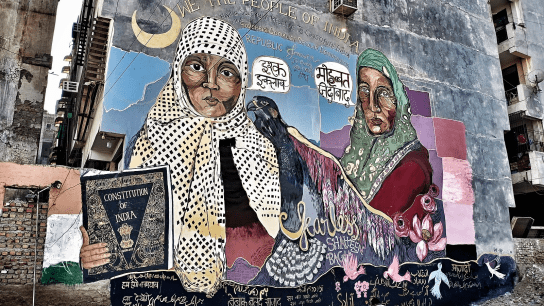

I have thought often of Aai’s phrase during the pandemic year as I’ve travelled several times to Mumbai to see her, without her beloved Lucy (whose US passport makes it impossible for her to enter a virus-stricken India). I have thought of what it means to remember a history lost and/or unseen in a country besieged by memory disputes, where little separates the factional from the functional. Even as India buckles under the weight of rampant authoritarianism, communalism, casteism, and a general disregard for human life, I remember you. I remember the promises of liberation, the mandate to agitate, organize, and educate. I remember the farmers’ protests, the words of Nodeep Kaur, the joyous rhythms of Shaheen Bagh, and the refusals of Bhima Koregaon.

“To summon a history of abundance is not to be restored to value, but rather to be set adrift upon more intrepid economies of meaning—sometimes harmonious, sometimes dissonant–that come together to upend genealogies of historical recuperation and representation.”

As I write this essay and heartbreak stretches across India, where more fires are lit to cremate than to create, there are more memories to be made. From the searing faces of my Dalit/Bahujan kin who tend the dead in the crematoriums of Hindutva making, to the oxygen-lungar that provides breath to the as-yet living, we remember. A cremator in Delhi “at the Center of India’s Covid Hell,” the byline reads, weeps; he is, after all, the only witness, the only record of the living dead. Ashu Rai is his name, always a Dalit, yet now the bearer of last rites, of data un/processed, of bodies un/spoken. “Almost everyone asks about my caste because everyone wants a Brahmin to do the rituals and not the Dalits, but they aren’t available,” Rai says. “We are.” Drenched in sweat, bearing wood, he takes one remaining piece of cloth, covering his face and head, and whispers laughingly: “This cloth … absorbs [my] sweat and …when I hang it on my shoulder, people think that I am a Brahmin priest.”4 I am a Dalit, I am the record of your loss, I am, I am, I am not your data. I am abundant.

***

This piece is an excerpt from Arondekar’s book Abundance (Duke University Press 2023). This republishing is part of the Care and Repair series, exploring topics and projects in conversation with the annual theme shared by UCHRI and the UC Humanities Network.

- https://roundtableindia.co.in/lit-blogs/?tag=abhay-xaxa

- https://roundtableindia.co.in/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=9953:i-am-not-your-data-nor-am-i-your-vote-bank-in-memoriam-sociologist-and-activist-abhay-xaxa-2&catid=119:feature&Itemid=132

- Xaxa’s words are a clear tribute to the pioneering work of Dr. B. R. Ambedkar and his insistence on caste as an enduring theoretical calculus and vocabulary.

- https://www.vice.com/en/article/y3dggy/we-spoke-to-a-cremator-at-the-center-of-indias-covid-hell