Migrant Labor and A Life Under Fire: A Triptych

by

From the early 1990s–2014, my father, Juan Zárate, owned a weed abatement company that was contracted by the County of Orange to create “fire breaks,” also known as defensible spaces, to protect property from fire in rural and unincorporated regions of the county.

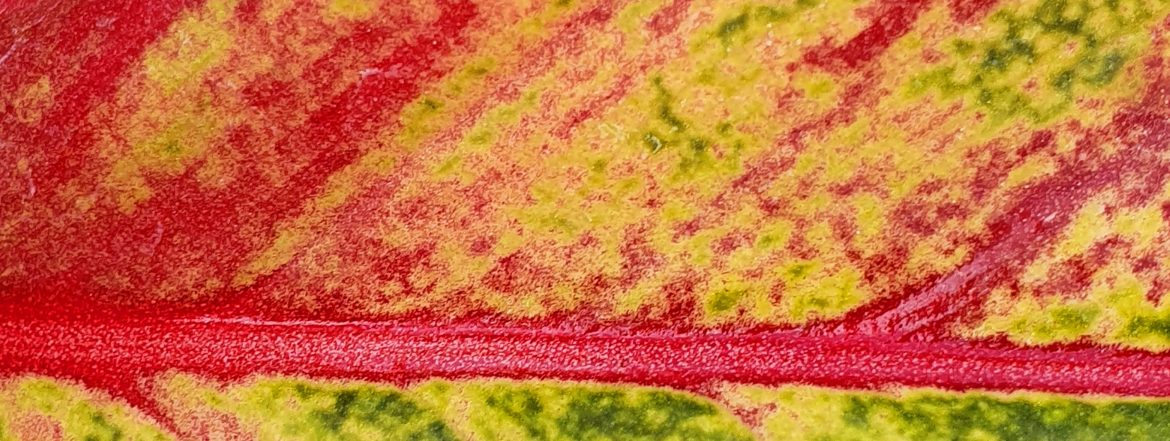

This invisible Latino, often undocumented, migrant techne clears the county’s canyons and foothills of dead and dry native chaparral plant life and destroys and hauls away non-native flora. Their work, using weed whackers, shovels, and machetes, clear the plant life that poses a fire risk by growing too close to county structures and private property.

What is the epistemological and physical labor required for preventing fires in the county? What is the social life behind this labor?

I draw on over three decades of my father’s weed abatement work as well as my own labor in the industry—I worked with his company throughout my youth and helped run it well into my PhD career—as a way to consider the physical, epistemological, and generational costs to preventing wildfires in Orange County as uniquely predicated on migrant precarity.

I write from the social, physical, and embodied memory costs that now eek into my intellectual labor as a faculty member for the University of California, Irvine, a land-grant institution on the land of the Tongva and Acjachemen people, that, for decades, my labor, as well as my father’s, protected from fire. It was protected by the expansive weed abatement work of the surrounding region: Laguna Beach, Newport Beach, Dana Point, Tustin.

That is to say, my physical labor, which protected the university and surrounding communities from fire, is a formative relationship that now captures and colors my position working within it.

What does it mean to poetically think about the long-arc of ethnographic research? How I worked for the university long before I was on its payroll. How I worked for maintaining the university even as an undergraduate student who was academically disqualified from its classrooms.

I think of the weight of memory as it sinks into and weighs down my physical, intellectual and surplus labor, as a racialized migrant, to understand how weed abatement labor quite literally and complexly reproduces settler claims over unceded native lands as the precept to a regime of knowledge production.

Clea in the Chaparral

“Clea’s parents don’t like her boyfriend. The guy in the cape, Dr. Strange.”

“Well, her parents don’t even like each other really.”

“Umar and Dormamu, Clea’s parents, they have the power to end entire worlds– dimensions– by swallowing them up in flames.”

“¿Porque no se queiren? Porque viven en otro mundo?” Miguel, a weed abatement worker for my father’s company, asked between bites of Albertson’s chicken pinched between two sweaty pieces of white bread. This was a lunch that my father’s weed abatement crew regularly ate as a special end of the work-week lunch.

I pause to think about his question for a moment and cannot come up with an answer.

Our lunch breaks were held wherever we happened to be working that day. These were locations amidst isolated chaparral spanning most of the south of Orange County, sometimes near the top of slopes in communities that dot the Santa Ana mountains, like Majeska and Silverado Canyons, on other days, like that day, we ate and rested at the bottom of foothills in exclusive planned communities. In both cases, the workday was composed of scaling steep-gradient foothills as we cut down non-native weeds that grew all the way to the backyard property line of homes.

I would think about Miguel’s question all week and decided I would have an answer for him the following Saturday. Perhaps I could even snag his attention on some weekday when my dad and his crew arrive at our home in Santa Ana for a brief period of time, just long enough to unload equipment.

I couldn’t hear it then, but Miguel’s inquiries were deep contemplations more than they were queries about the over-sized Steve Ditko Dr. Strange comics that my brother and I read and shared with him on lunch break during the spring of 1995.

As fires grow in scale and frequency in recent years, my focus on answering his question has been dwarfed by a consideration of the valences behind his interest in engaging with the text in the first place.

I think about resonances not answers.

I think about how my memories are colored by our work in the isolated chaparral estates and the way we enacted a kind of power all our own: a kind of labor that wove protective wards into the ecology.

Our work, I imagine myself continuing our conversations with Miguel, created protective cyphers on the earth floor, composed of broken up soil, redirected plants, and mathematical divisions, as a way to create a “defensible space” of cleared vegetation and biofuel. Our wards sealed, at least momentarily, propertied worlds from conflagration.

Not quite Umar and Dormamu and not exactly Dr. Strange and Clea in the chaparral, the worlds we upheld through our labor were neither ours to inhabit nor ours to do away with. We were between the panels, between worlds, functioning as if suspended on some sort of invisible overlay, doing the migrant work of maintaining the very division between safety and risk, flames and propertied futures.

That I never had the chance to give Miguel an answer has stayed with me for decades. I have held onto my thoughts and given up on an answer because in the following week, Miguel was deported– moved from our world to another, slipped away, violently.

I wasn’t able to get back to him with an answer but I imagine that a part of what he might have heard in those tales about clashing worlds was always already inscribed by the ecological wards of protection left in his wake on Orange County canyons. These chaparral manipulations carried like spells, formidable and stalwart even as they failed to secure ground on which we could safely walk.

How to Restring a Weed Whacker: Santiago Canyon

“Fuck Prop 187”

the People of California declare their intention to provide for cooperation between their agencies of state and local government with the federal government

I tagged it with orange-color marking spray shot out of a canister onto a dry cluster of mustard grass. With the sounds of a marble bouncing off of the walls of the cylinder, I continued to mark native chaparral plants so that they would not be cut by the crew of weed abatement workers.

I figured we were tucked away into the Santa Ana mountains, who would notice my tag? Here, hidden by an oak canopy, shin deep in dry grass?

and to establish a system of required notification by and between such agencies to prevent illegal aliens in the United States from receiving benefits or public service in the State of California.

Later, in high school, I would learn that this area of Santiago Canyon that I had cleared for many years was also known as Black Star Canyon.

You might know Black Star Canyon, if you grew up in Orange County, as the site of local urban legends. Some would say that it was the hunting grounds of the Orange County KKK. Others said that it was haunted.

These are anti-Native retellings that continually relegate Native Tongva peoples and their relationships to the land to the past.

Black Star Canyon was the site of a massacre of Tongva peoples in 1831 by white settler ranchers and trappers.

Orange County remains the unceded lands of the Acjachemen and Tongva peoples.

I had seen “Fuck Prop 187” tagged with a silver chromatic permanent marker on the exterior wall of my Junior High’s sixth grade English classroom in Santa Ana just days prior.

Feeling proud of my handiwork, I return to my father’s truck and begin restringing some weed whacker heads so that his workers do not have to spend time doing it themselves.

I hold their heads open and remove their face by pinching their edges.

I unspool and cut plastic wire and feed it through the head and loop it into circles.

Over and over until the knot tightens.

I then seal it all up.

“I got the weed abatement contract with the county,” my father said. “It’s for four years. We’ll be here to work it.”

As a youth I’m filled with a feeling that my life is being unspooled by anti-immigrant legislation overwhelmingly supported by the xenophobic nativist population of the state.

At the same time, I hope that in some way my father’s contract, our work, might protect us.

Goats on Turtle Rock

I’m running errands in my car and hear on news radio, in one of those general interest make-you-feel-good kind of piece, that “there is a new tool in the fight against wildfires.”

Listeners, the radio host noted, could go see these “new workers on the front line of fire protection in action, gobbling up their lunch as they work on the bluffs of Newport Beach.”

A week earlier, a childhood friend, whose family was one of the many Black families in our historically Black neighborhood in Santa Ana, sent me a picture of the goats as they worked in the Turtle Rock neighborhood above her home, an affluent community just down the street from UC Irvine.

She told me that it made her think of my dad and his work.

She could see my dad, where others could not. Even when he actually wasn’t there.

Since my father’s passing, I think of his weed abatement work on those hills overlooking Turtle Rock, UCI, unceded land of the Acjachemen and Tongva peoples.

Maybe you see him?