Monsters and Imagination

by

Responding to the theme of Care & Repair, UCHRI is republishing select pieces from The Humanities Institute (THI) at UC Santa Cruz faculty series. Together, these scholars from different disciplines meditate on the healing capacities of memory, imagination, and travel to explore their potential for care and repair. To read the essays in their original context, see the THI series on Imagination, Travel, and Memory.

“The monster in the mirror, then, is as much an opportunity for self-reflection, awakening, and growth as it is for exclusion and marginalization.”

Devotees of the critical theoretical school known as “Monster Studies” are keenly aware of the power of imagination not only for its facility in envisioning constructive and edifying utopias that we might strive to achieve in the waking world, but also for its capacity to retrieve and magnify the darkest parts of our being. It is after all in the imagination that monsters exclusively lurk. Their domain is the bad neighborhoods of the phenomenon Jung called the “collective unconscious,” that library of images and emotions that we as a society share through storytelling, art, performance, and music. There they wait as glyphs, ideas in potentiae needing only a new story, a new piece of art, a new folktale, or a new social trope to emerge to give them cultural form to terrorize us once again. Which they do, to our horror and/or delight, depending upon our own personal relationship to the strange, and then back they go to prowl the darkness beneath our consciousness, waiting for the next time they can appear with their compelling malevolence.

But they don’t always go quietly—sometimes, imaginary monsters linger in the waking world long enough to cause real trouble. For we find that the human mind has a propensity to more or less effectively map the imaginary, cultural body of the monster onto the living bodies of real people. Whenever this happens, this process results in dehumanization, marginalization, and persecution. Indeed, this is, I observe, a precursor to atrocity, because only after the human being is reimagined as a monster does atrocity become possible—at least for human beings who consider themselves sane, and who are in the dominant majority and therefore have the power to call the imaginary into being in service of persecution.

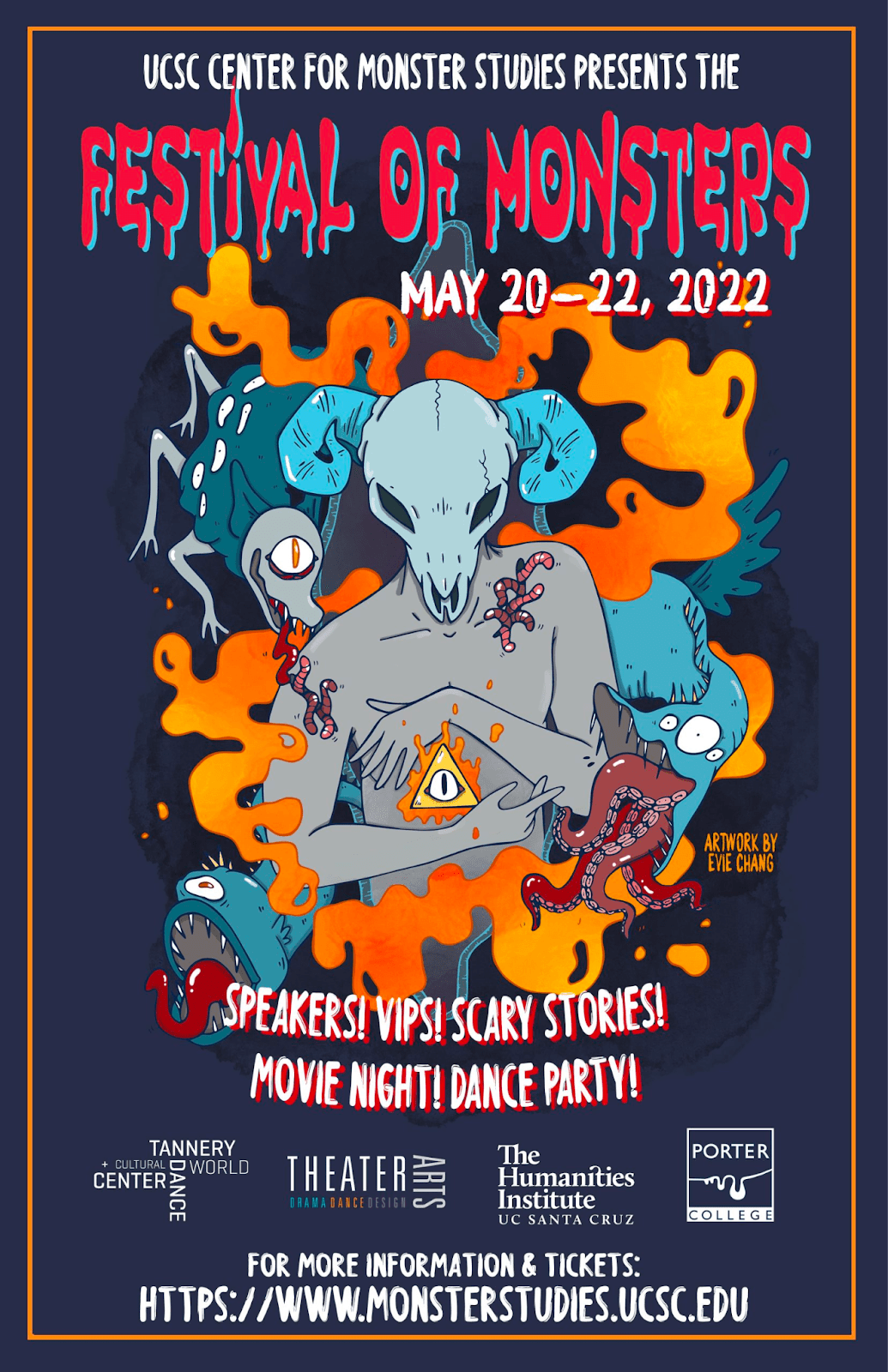

The Festival of Monsters Conference was held May 2022.

The Festival of Monsters Conference was held May 2022.I witnessed this process in my own small way growing up as the only Jewish kid—dark, pudgy, and nosed—in an environment where almost every other kid was a blond, blue-eyed, slender Mormon. My Jewishness hung like a cloud over every interaction. I was repeatedly asked by other children whether it was true that I had black blood, horns, and a tail, and whether it was true that Passover matzoh was made with the blood of Christians. These interrogations were followed, often as not, by thrown stones, punches and kicks, and eventually cries of “dirty jew” and “kike.” Adult playground monitors and teachers looked on with expressions of indifference.

I didn’t know what a kike was—I had to ask my father. The other kids didn’t know what a kike was either, it was just something they had heard their parents say, but they could imagine it very well—whatever it is, it is something dangerous, something pernicious, with a tail and horns, something subhuman that needed to be driven from the community, with violence if necessary. I distinctly remember looking into a mirror and experiencing the image it held as multiple—myself, and myself as bestial, as cadaverous, as demonic—as a kike, whatever that was. I had no idea there was any element of this that was not personal. How others imagined me was predetermined, and how I imagined myself was always yet-to-be-determined.

“The same quality of the monster that makes it so useful for persecution and atrocity also opens it up to the possibility of genuine awareness of others.“

My little story of playground bullying is not much when held up against the violence that nonwhite persons in the United States have experienced over the past five years, when imagining nonwhite Americans as monsters experienced a new surge. Crimes against people because of their race, religion, sexual orientation, gender identity, or disability have been rising steadily since 2017. But my little story is a microcosm of these events, one which, when examined, can demonstrate the awesome power of the imagination when it comes to discourses of marginalization and persecution.

But Monster Studies urges us, as critics of our culture, to recognize not only the other in the monster but also the self. The same quality of the monster that makes it so useful for persecution and atrocity also opens it up to the possibility of genuine awareness of others. Whenever we are able to imagine the self in the other and the other in the self, we expand our ability to empathize. The monster in the mirror, then, is as much an opportunity for self-reflection, awakening, and growth as it is for exclusion and marginalization. Precisely because we can see both the self and the other in the monster, monsters provide a medium in which we can experience deep compassion for one another—compassion that with any luck will lead to the adoption of social policies that are inclusive and just. At the end of the day, that is what Monster Studies is really all about—figuring out how to harness the vast and complicated power of the human imagination in the service of better realities for living people.

***

This essay is part of the Care and Repair series, exploring topics and projects in conversation with the annual theme shared by UCHRI and the UC Humanities Network.