Oversharing in the Academic Borderlands

by

How do tensions between refuge and its refusals shape the nature of university labor, especially in light of recent upheavals? From the protest encampments on UC campuses to memory landscapes of Iran and trans activists in South America, UC PhD students in UCHRI’s 2023-24 professionalization program map the search for refuge from local to global.

When does the personal belong?

It’s nine a.m. on a winter’s Wednesday. I am 23, a second-year in my PhD program, and I am not doing well. I demonstrate as much when, in an effort to queer the genre of the seminar paper—and by “queer,” I mean “transform into a vehicle for oversharing”—I recount walking down Ohio Avenue in Sawtelle with intrusive thoughts of stepping into traffic. I feel compelled to write this anecdote, and then I feel weird about turning it in. Anticipating a referral to the counseling center, I send a follow-up email about my assignment submission. I clarify that I am already seeing a therapist, and that I am trying to be intentional in my inclusion of the personal, although I’m not sure if it’s working—is it working? I am wondering if it could work.

It’s worked in the sense that I’ve turned something in—a few hours past the deadline, which I forgot had an hour attached to it. But has the seminar paper worked enough that I can transform it into an article, which is how my undergraduate advisor told me to look at every seminar paper in graduate school?

I wait, feeling embarrassed and exposed.

The professor responds and suggests that I think about the personal as scaffolding: something I use to create the first draft that will fall away in the revision process, that I can keep for myself, that doesn’t need to be there in the end. This feedback follows me to my final year, in struck out paragraphs and accompanying comments: Consider. Does this personal story belong here, in your dissertation, which is your scholarly contribution to the field?

When does the personal belong?

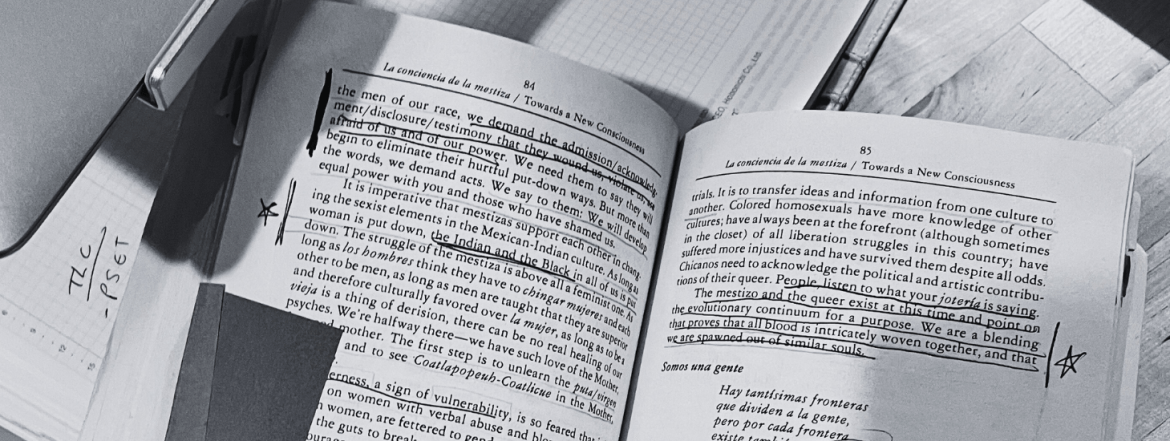

When Gloria Anzaldúa mentions writing “while sitting on the John” in “Speaking in Tongues: A Letter to 3rd World Women Writers,” I feel grateful that, for me, the need to multitask has not coincided with the call of nature. Before Gloria Anzaldúa was Gloria Anzaldúa—a Chicana feminist icon, rejected and celebrated, and rejected and celebrated again—she was a writer and a graduate student. She often missed deadlines. AnaLouise Keating—expert in US women-of-color theories, friend and colleague of Gloria Anzaldúa, and trustee of the Gloria E. Anzaldúa Literary Trust—suggests that “missing deadlines seems to have been a regular part of her writing process.”

From 1965 to 1972, during the campus agitations that led to the formation of ethnic studies departments across the US, Anzaldúa pursued a BA and then an MA in English and education from Pan American University and UT Austin. From 1974 to 1977, she enrolled in doctoral studies in comparative literature, before, as Keating narrates in The Gloria Anzaldúa Reader, deciding to drop out “to devote her life to her writing.” Anzaldúa moved to California, supporting herself through lecturer jobs and other part-time work, before eventually applying to graduate school again in 1988. Though she was rejected by the History of Consciousness program she applied to at UC Santa Cruz, she was accepted to study literature. Still, throughout the 1990s, she took on teaching positions, speaking engagements, and other work that would draw her away again. In 2003, she would return to Santa Cruz, determined to finish her dissertation. She would die of diabetes-related complications in 2004, and her degree would be conferred and her dissertation published posthumously as Light in the Dark: Luz en lo Oscuro (2015).

Anzaldúa was a bold writer and remains a polarizing figure. Her death haunts present-day discussions of her work, particularly since she was so grounded in community with other scholars, some of whom have expressed frustration with what they see as harsh or unfair reactions to her work today. For example, writing about the Gloria Evangelina Anzaldúa papers—the vast archive assembled at UT Austin—Keating asserts her hopes that the archive might serve as a corrective to “sloppy scholarship, unfair judgements, and a narrowed focus” on Borderlands/La Frontera over Anzaldúa’s more contemporary writings. Keating further suggests that the canonical status of Borderlands tempts “scholars to use the text selectively, criticizing a single aspect” to “develop their own careers”—this, despite the fact that “[Anzaldúa] did not power down her computer and stop writing” after Borderlands was published in 1987. Likewise, Emma Pérez—Anzaldúa’s queer Chicana feminist contemporary and friend—laments in an open letter that “little critics” rely on the same José Vasconcelos reference from Borderlands to label Anzaldúa as anti-Indigenous and anti-Black. She expresses anger and sadness over hearing someone characterize Anzaldúa’s work as “‘chains’ for an up-and-coming population of critics”—Anzaldúa’s theories, in other words, dismissed as burdens, limitations, outdated impositions. Pérez continues to address Anzaldúa in her letter: “You said to me once, ‘I wish I’d known not to use Vasconcelos in Borderlands/La Frontera.’ And then you explained that you had only wanted to publish the poetry in that book but your editors insisted you go home and write essays to elucidate the poetry. It was the mid-1980s, after all.”

As a gay, woman of color feminist, Anzaldúa embodies the “minoritarian”—yet her legacy also lays bare…those places where solidarity breaks down.

As Pérez narrates, Anzaldúa was pressured by the labor of explaining herself to reading audiences without the critical infrastructure and context by which scholars are able to dismiss her work today. Anzaldúa read Vasconcelos “too quickly” to notice his racism: “A whole new feminist and queer and Brown era was starting to be conceptualized… There was so little that came before our own writings, and often what existed was intensely problematic.” Pérez returns to Anzaldúa’s training, and the ironies that time has wrought as the field has grown and changed: “Your work, your nonformal training, is criticized by those with class privileges, with PhDs from premier universities, with race/gender/heteronormative privileges—all these privileges that allow for intellectual critique and engagement—things you didn’t have.” Pérez’s blanket characterization of Anzaldúa’s critics as privileged reveals how neoliberal multiculturalism has shaped how we discuss power dynamics in academia. As a gay, woman of color feminist, Anzaldúa embodies the “minoritarian”—yet her legacy also lays bare those fractures within minoritarian scholarship, those places where solidarity breaks down as we (and by “we,” I mean Chicano studies) become defensive.

I get a taste of this generational divide at the 2024 National Association for Chicana and Chicano Studies Conference, when I attend a panel of senior scholars recounting histories of the field. One professor says that she gets angry that junior faculty are so critical toward their colleagues, adding that they came up after the Chicano Movement and never had to fight for a seat at the table. The personal is political is personal, I think. I wonder about respect—about the ways that tone plays into our reactions to each other, and the ways that policing tone can distract us from engaging with critique. I like to think that I’m not sentimental about Anzaldúa—that I know better, because I’m not calling Borderlands “the Bible” like my friend did that one time in seminar, because I’ve read the critiques—but my work on Anzaldúa thrives on sentimentality, because I can’t help but love her drive towards mess, towards hoarding, towards hybridizing. I can’t help but love writing that is bad, that doesn’t cohere but gets circulated anyway because that’s how you think in community.

I wonder about…the ways that policing tone can distract us from engaging with critique.

Before I was a graduate student, I was an undergraduate student trying to get accepted into a PhD program. I name-dropped Borderlands in my application without having read it—it was the only Chicana feminist text I’d really heard of. A Chicana from Northern California who I met in England had recommended it to me. This is how, despite having no background in Chicano studies—no background, really, in any critical theory, given my undergrad alma mater’s commitment to a liberal arts education grounded in the Catholic intellectual tradition—I tried to gesture to the work I wanted to do, iconizing Anzaldúa without really engaging her.

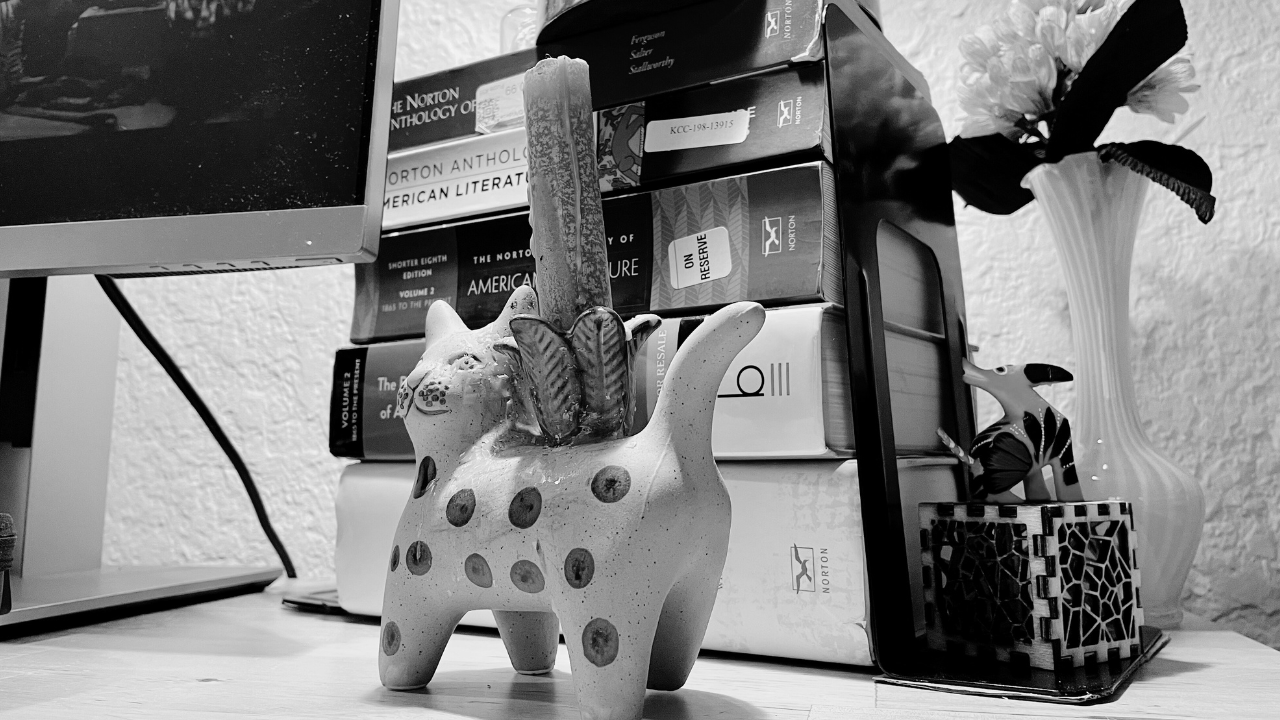

I didn’t have time to read Borderlands because I had to work on a new writing sample, so that I could get into graduate school, so that I could understand Borderlands. Anzaldúa recognized her tokenization as it was happening, noting in an email dialogue from 2002 (“written at the request of her good friend, Inés Hernández-Avila”) how her work was being excerpted in various anthologies—the Norton, the Heath—which coincided with increasingly rote citations of Borderlands and the radical feminist anthology This Bridge Called My Back (1981), signaling a process of containment via depoliticized institutional inclusion. In the email, she writes: “I am cited by ‘whites’ mostly for my work in Borderlands and This Bridge Called My Back, but often it’s a mere referencing and not a deep exploration.” I am given the opportunity to engage in a deep exploration of Anzaldúa’s work when my dissertation committee asks me to add a chapter about her to the beginning of my project, to ground it in the 1980s. I find, when I write about Anzaldúa, that I also write with her process.

The time Anzaldúa spends documenting her writing practice makes me document my own: I write about the candle that I light whenever I work on the dissertation, a candle which I fear and hope conjures her ghost. I write about the 2022 UAW strike, about sitting in Sawtelle coffee shops with A, a friend from my cohort. I vent to her that I can’t get a chapter draft done and also go to the pickets, but I really need to get a chapter draft done because I need to have something to show for my first year on fellowship. I quote A in the epigraph of the first draft of the first dissertation chapter I eventually produce: What kind of writing are you going to do on $24,000 a year? I also quote Anzaldúa talking about needing time and not having it: about time as a commodity. I wonder if I end my chapter drafts with personal tangents because I am an underwriter and will always be an underwriter, or if it’s because I’m running out of time and will always be running out of time in this profession.

What kind of writing are you going to do on $24,000 a year?

What does it mean to hybridize genres with intent? Have I done it here? Has it worked? The first draft of this article curls with self-consciousness. I worry the structure is weak because I missed the retreat where I was meant to workshop a pitch of this article with an editor. This retreat would’ve been—was, for my colleagues who attended—the culmination of the UC Humanities Research Institute’s Work & Refuge: The Future of Graduate Student Professionalization program, which funded 10 graduate students to develop articles for publication and meet for professional development workshops and networking opportunities across the 2023-2024 academic year.

I miss the retreat in May 2024 because it comes around at the end of the week that the UC Los Angeles Palestinian solidarity encampment has been attacked by counter-protestors and then violently swept by the LAPD, the California Highway Patrol, and the LA Sheriff’s Department, and I want to be with my friends. I also have to work on my final dissertation chapter, which I need to finish as soon as possible in order to send a completed manuscript to my committee before the end of May. I write about the encampment sweep in my last chapter, calling Israel’s war what it is: a genocide of Palestinian people. This writing exposes personal and professional fractures I am scared to address. I don’t have a job, but I need to get out. I need to stop being a student and start being an employee, though my advisor has always told me to think about graduate school as a job, as a performance.

What performance is this?

It is a performance of my reticence as a job-seeking, recent PhD, writing about the power dynamics I experienced in graduate school. Has it worked? Do I work, here? As I write this, nearly five months after graduating, I am still trying to figure that out.

Banner Image Credit: Sammy Solis

This publication was supported in part by the University of California Office of the President MRPI funding M22PS5863. UCHRI thanks editor and writer Michelle Chihara for her developmental work with the series contributors.