Reparaciones

by

Responding to Care & Repair, the annual theme set by UCHRI and the UC Humanities Network, UC Merced faculty Lorena Alvarado and Yehuda Sharim offer an intimate peek into the Huntington Park neighborhood of Southeast Los Angeles. We invite you to be transported by Sharim’s photographs as you experience Alvarado’s poetry. The introductory essay includes both English and Spanish versions.

Reparaciones (English)

Orange-hued, with an open center and a raised platform by the side, Elvi’s clothing alteration workshop is a one-room stage of possibility, a platform for metamorphosis. He and his small staff operate two sewing machines on view, behind a glass counter where sequins glisten and a helicoid tape ruler hangs from the edge, the essential tool to measure waistlines, the breadth of the back, necklines… Today, as most days, a tape ruler is suspended from his neck as he fixes his gaze on the lightning-speed stitching happening between his fingers. Outside, one is steps away from the main boulevard of Huntington Park, Pacific Blvd., or la Pacifi to my ears, a commercial corridor with a variety of stores. Clothing shops abound. For many tailors like Elvi, part of their task is to transform an outfit, perhaps make an entirely new one, or simply alter clothing. Many Spanish-speaking tailors, who often make a living as garment workers, will refer to their trade as “hacer reparaciones,” to make repairs, an evocative choice of words that conjures textiles, meticulous hands, and the machine, but also racial reparations here in the United States, campaigns to address the heinous, ongoing effects of slavery, economically and symbolically, in all areas of public/private life and in all institutions, for Black people. While Reparaciones does not directly address reparations in this latter context, it’s important to note the intersecting connotations of the term, which echo in the meaning of mending, “efforts to repair what’s torn, to create something like a whole from fragments.” 1

The images of Reparaciones by Yehuda Sharim invoke a cycle of the doing and undoing of fabrics, material and social, the threads that clothe our bodies and the relations that sustain our life, that resist the ruptures and absorb the shocks that we inevitably encounter in all stages of life: be they school lunch rejections or the chronic silence of those we love or have loved. These photographs are grounded in Huntington Park, in Southeast Los Angeles, Tongva and Chumash unceded lands. I was raised there, in a largely Spanish-speaking, immigrant city that has, and continues to be, a source of Quinceañera boutiques, stories, wounds, stitches that endure.

“Reparaciones—the term resounds a fixing of torn fabrics and inner wounds, the hemming of pants or dresses, the care that comes with injury, the undoing of thread to adjust a sleeve onto our bodies.”

On Pacific, official and unlicensed commerce flourishes. Commuters wait for buses. Puppies are sold furtively outside The Children’s Place, a relative newcomer to the boulevard. I remember, years ago in my daily walks there, the kind smile of a middle-aged man without shoes, offering me and others he passed by the chiclets he sold. Here, an art deco Warner theater has been rehabbed into a gym, and battery-operated dog toys lined along some storefronts bark incessantly at the pedestrians. Sometimes, those asking for money reveal their open wounds. Increasingly, tents are set up along intersecting streets—a sign of the acute crises befalling our communities in the early 21st century.

Reparaciones—the term resounds a fixing of torn fabrics and inner wounds, the hemming of pants or dresses, the care that comes with injury, the undoing of thread to adjust a sleeve onto our bodies. These clothing alterations have an impact beyond just making an outfit wearable. Such revisions are potentially life and world-altering, too, as they extend the life of our ensembles or enable the elation of seeing ourselves in something otherwise inaccessible. The idea of mending evokes, as well, actions of repair and disrepair unrelated to attire. The images and poetry of Reparaciones hail both acts—modifications to our clothes, and the world at large that surrounds and envelops us.

“These pictures are a meditation, and a humble dedication, to the community that traverses, plays, works, repara, in la Pacifi, in the corridors of Southeast L.A.”

H.P. and la Pacifi are a personal, perpetual inspiration, as are perhaps childhood imaginaries for most. But beyond its hometown mystique is also its sobering landscape, the dwindling crowds across the years, the growing ‘for lease’ signs, and my gaze into the echoes of an abandoned suite. La Pacifi, growing up, was a place some friends would rather avoid, preferring to go to Downey’s Stonewood or some other mall farther from Southeast LA. It wasn’t trendy, had no brand name stores, it was our own backyard. It taught me the stories carved onto its concrete, onto its storefront security gates, the ephemerality of the street corner, as people pass and wait, as it hosts changing offerings: Mexican wood furniture store, to TV doctor pharmacy, to Winchell’s donuts.

Sharim’s photographs of la Pacifi and its surroundings—be they commercial spaces or domestic scenes—are accompanied by my poems. The text may capture details present or absent, heard or unheard, remembered or forgotten. The title image evokes these termini: the satined curtain adjacent to the raised platform, where a mirror also stands, showing us the other side, inviting us to step in, to be seen, to reveal what we finally put on and are eager to see complete, behind the drape that provides some modesty. That lavender pink drape, or what it occludes, also reminds us of the people manufacturing our clothes, the body of the worker beyond our sight in some sweatshop in H.P., in downtown L.A., or elsewhere abroad due to offshoring. Behind that panel is the one that stitched the label, where they will never write their name. Some of these images are evocative, for me, of people we don’t see anymore—they walked by too fast before we said hello. Or, we lost them too early. These pictures are a meditation, and a humble dedication, to the community that traverses, plays, works, repara, in la Pacifi, in the corridors of Southeast L.A.

– Lorena Alvarado

Merced, CA

Prenda de mi alma: des/haciendo tejidos en Pacific Boulevard y Reparaciones (Español)

El taller de reparaciones de costura de Elvi es ámplio. Las paredes están pintadas de color anaranjado. Hay una tarima al lado izquierdo del local—su taller es un escenario de modificaciones, una plataforma para la transformación. Elvi y su pequeño personal operan dos máquinas de coser que, al entrar al taller, están a la vista detrás de una vitrina desde donde resplandecen lentejuelas. Una cinta, herramienta esencial para medir el cuerpo, cuelga de la orilla como onda suelta de bucle. Hoy, como casi siempre, otra cinta se suspende de su cuello mientras su mirada se concentra en la aguja que cose a toda velocidad. Afuera del inmueble, la calle principal de Huntington Park, Pacific Boulevard, o la Pacifi como se pronuncia seguido por acá, está a unos pasos. La Pacifi es un corredor comercial con una variedad de tiendas, especialmente tiendas de ropa. Para muchos costureros como Elvi, su trabajo consiste en transformar un traje, o hacer uno nuevo, o simplemente arreglar un detalle. Aveces, costureros, algunos de los cuales se ganan la vida como operadores en grandes fabricas, mencionan el “hacer reparaciones” al describir su labor. Esta frase evoca el arreglo de la ropa, pero también las reparaciones raciales aquí en los Estados Unidos, las campañas que exigen recompensaciones materiales, económicas y/o simbólicas por la esclavitud y sus consequencias atrozes en todas las esferas de la vida pública y privada de la comunidad afroestadounidense. La exhibición Reparaciones no se refiere directamente a este último contexto; aun así, es importante notar los significados latentes dentro del término, que hacen eco en el sentido de “remiendo”: “esfuerzos por reparar lo roto, crear un conjunto con lo fragmentado.”2

Tanto las imagenes de Reparaciones por Yehuda Sharim, y mis poemas que las acompañan, invocan el ciclo de hacer y deshacer tejidos—tanto materiales como sociales—los hilos que arropan nuestros cuerpos y los enlaces afectivos que sostienen nuestras vidas, que resisten las rupturas y amortiguan los impactos que encontramos inevitablemente en distintas etapas de la vida, ya sea rechazos en la fase estudiantil, o el silencio crónico de nuestros seres queridos. Reparaciones—en el termino resuenan las telas rotas y las heridas interiores, las bastillas por hacer de los pantalones o vestidos, el cuidado que exigen las lesiones, el descoser para rehacer una manga sobre nuestros brazos. Estas alteraciones impactan mas allá del arreglo de una pieza. Tales ajustes a las prendas de vestir, y a las prendas del alma, nos pueden cambiar la vida. Prolongan el uso del vestuario, invitan a la singular felicidad de sentir algo que de otra manera sería inacesible, facilitan, tal vez, el encuentro con álguien que nos escuchan sentires que no se pueden medir.

“Reparaciones—en el termino resuenan las telas rotas y las heridas interiores, las bastillas por hacer de los pantalones o vestidos, el cuidado que exigen las lesiones, el descoser para rehacer una manga sobre nuestros brazos.”

Las imagenes y poesia de Reparaciones llaman a la acción de remendar mas allá del ajuar, tanto a las medias como al mundo. Reparaciones esta enraizado en el Sureste de Los Angeles, tierras Tongva y Chumash. Allí me crié, en una comunidad inmigrante de habla hispana. Es y ha sido destino (tan brillante como disonante), espacio vibrante de multitudes que visitan de cerca o de lejos, fuente de boutiques de vestidos de quinceañera, historias, heridas, puntadas que perduran.

Años atras, la Pacifi fue un lugar que algunas amistades, vecinas mias, evitaban, pues preferian ir a Stonewood en Downey o algun otro mall lejos de Southeast LA. La Pacifi no prometía el escape de nuestras vidas o comunidades de clase trabajadora. El comercio oficíal y el ilícito prosperan de igual manera en la Pacifi. Gente espera el autobus. Se venden cachorros bajita la mano afuera de The Children’s Place. Recuerdo hace años, en mis caminatas diarias en la calle, la gentíl sonrisa y palabras de un hombre descalzo que vendia chiclets. Aquí, el cine de Warner, construido al estilo Art Déco, lo han transformado en gimnasio, y perros pequeñitos de jugete le ladran sin parar a los transeuntes que caminan con prisa, o se pasan buen rato haciendo sus mandados entre los ladridos mecanicos. Aveces, los que piden comida o dinero exhiben sus heridas abiertas. Carpas de personas sin vivienda aparecen en las bocacalles principales con más frecuencia, otra seña de las graves crisis que nuestras comunidades enfrentan en el incipiente siglo 21.

“Esas imagenes son una meditación, una humilde dedicatoria a la comunidad que atraviesa, trabaja, repara, en la Pacifi, en los corredores del Sureste de Los Angeles.”

La Pacifi es, sin duda, una inspiración personal y perpetua, como lo puede ser el imaginario infantíl para muchxs otrxs. Pero mas allá del encanto que podría guardar la ciudad natal de cada quien, están tambien otras realidades desembriagadoras (tanto como embraigadoras): las llagas en las piernas del que tiene hambre en frente de algun local, las multitudes que ya no llegan, los letreros de arrendamiento o de renta que aparecen mas frecuentemente, y miradas fijandose en los ecos de una suite abandonada.

Las fotografías y los poemas se aproximan a detalles presentes o ausentes, audibles o inaudibles, recordados u olvidados. La imagen que acompaña al título de esta exhbición alude a estos términos opuestos: la cortina satinada que está para ocultar, justo al lado de la tarima que está para exhibir. En esa plataforma, se apoya un gran espejo para que el cliente se vea de cuerpo entero, un espejo que refleja el otro lado del espacio y nos invita a subirnos a la tarima, a ser vistos, a mostrar el traje que con ansias queremos lucír ya arreglado. Aquella cortina lavanda, y lo que oculta, nos recuerda a las personas que confeccionan nuestras prendas, al cuerpo del trabajador mas allá de la vista (un cuerpo entero que no se ve) en alguna fabrica en Huntington Park, en el centro del Los Angeles, o algun otro lugar en Bangladesh, India o Perú a causa de la deslocalización. Detras de esa cortina está la que cosió la etiqueta, la que no escribirá su nombre en ella. Algunas de estas imagenes sugieren los des/encuentros que vivios, los que vimos y ya no estan. O, a los que perdimos antes de tiempo. Esas imagenes son una meditación, una humilde dedicatoria a la comunidad que atraviesa, trabaja, repara, en la Pacifi, en los corredores del Sureste de Los Angeles.

– Lorena Alvarado

Merced, CA

***

Paradise is far from the freeway3

In memory of Michelle L. and Bree’Anna G., young Latinas from Lincoln Heights

Paradise is far from the freeway—Far from the highway exits and entrances, far from apartments overlooking the 5, far from the underpasses where women and men sleep, far from the CVS pharmacy at midnight, far from traffic lights beaming red, red, red; far from the hum of passing cars and catcalls. Paradise is far from the mute communicators of crisis lying on the shoulder of freeways: newspapers, empty soft drink bottles, dry shrubs.

The contents of plastic bags everywhere—Warning: keep out of the reach of children. These bags skitter along empty parking lots like purgatory souls. They hold trash and carry our lunches. Groceries. Your face, your hands, your hair do not belong there.

The different levels of justice—Justice refuses to look at our mothers. Justice refuses to clarify the crimes against their daughters. Justice does not visit our streets: Soto and State, Broadway and Lincoln, Avenue 26th. Justice loiters, looking beautiful. Where are the assemblies, the search committees, the witnesses, the closed palaces of justice? Who shall force open their doors?

Matching tattoos—the one you share with your mother. We saw Bree’Anna’s tattoos from the corner of our eye. Many of us are suspicious of young women with pierced lips, giving birth, or walking at night to the Rite Aid in Lincoln Heights. There are different levels of guilt, too.

Getting lost in the news—Among paparazzi and fashion reports, among interviews that are quiet tools of carnage, among weather reports that show more cleavage than climate, among breaking news that do not matter the next minute: I see your image.

Loves to bake—Bree’Anna was a chef at twenty-two. She meshed flour and sugar with her hands, singing along to Nicki Minaj. She decorated the finished cupcake slowly making shapes, swirls, her large brown eyes focused. Now silent.

Loves to walk—Mama, I’ll be right back. I’m going for a walk. Let me get my sweater cuz it’s a little cold. I need to unwind a little, listen to my music. Sit at the back of the bus down Figueroa, and meet my love.

Forever 21—I can see your pink bag in the background of your photograph. They have affordable accessories that hide the details of their making. Plastic bangles that last forever are the only witnesses to the crime against you.

The fur of a gentle cat—How do we hold the delicate lives around us, how close are they to our bodies? With what world did you want to share the recent webcam photograph with your cat?

She has my name—and she lives on my street. If you ask for her, you ask for all of us.

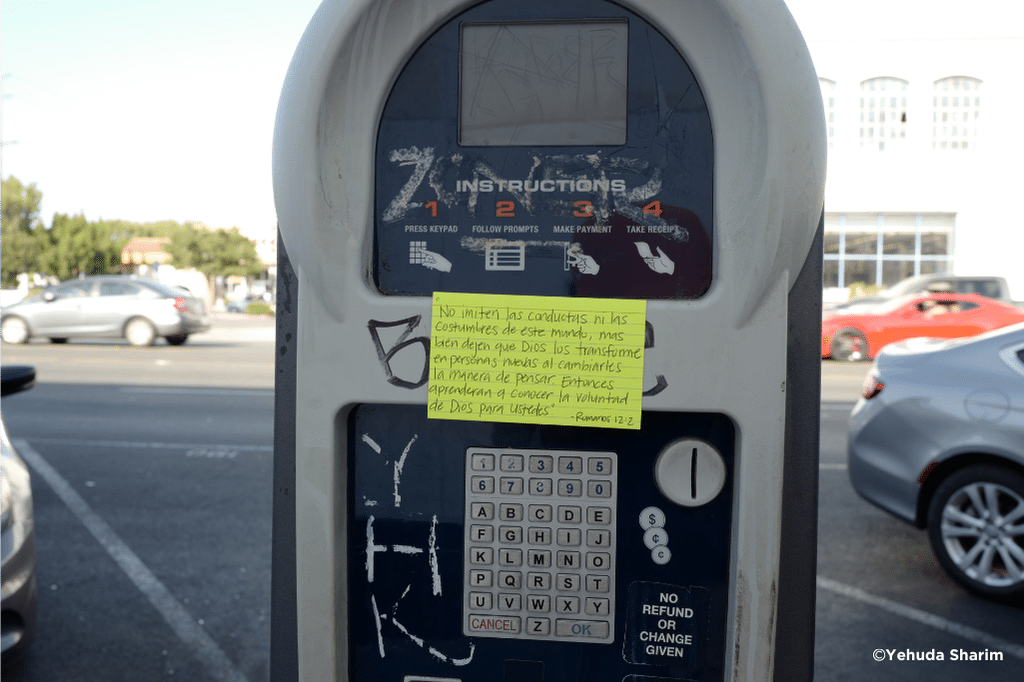

Que dice aqui, mija?/what does it say here, mija?

Que no te da cambio/that it won’t give you change.

Que cambió en mi rostro?/what changed in my face?

El arbol de tus ojos/the tree of your eyes

Se cae poco a poco/falls a little more each day

My hands hold too much

I cannot hold yours

I am in no hurry to step inside

And try

Something

Never made for me

Ya no me veo igual que antes/I don’t look like I did yesterday

Buscando mis reflejos/seeking my reflection

Sé llegar a mi casa/I know how to get home

Aunque ya no sea mi casa/even if I don’t live there anymore

En este mundo hay que buscar un lugar/you have to find your place in this world

Pa’ no andar dando vueltas/so as to avoid circling the vicious forest around

Rodando la casa que tanto quiero dejar/the house you wish to leave so badly

Someone waits, waits

For me

I haven’t taken this route before

But something waits, someone:

There he is, the singer of my angers, his hand that opens mine

And deposits in my palm

a gift of wild, untamed horses

Mija, apuntame tu direccion/write your address here, Mija

Donde, al lado de la oracion?/where, next to the prayer

Al lado de la oracion para/yes, next to the prayer

No sentir rencor/against resentment

Que es el rencor?/what is resentment?

Es el puño de garrero/it’s the bunch of clothes here

Que tengo que reparar/I still need to get fixed

Apuntame tu direccion/write your address

Alli, al lado/there next to

De la eternidad/ eternity

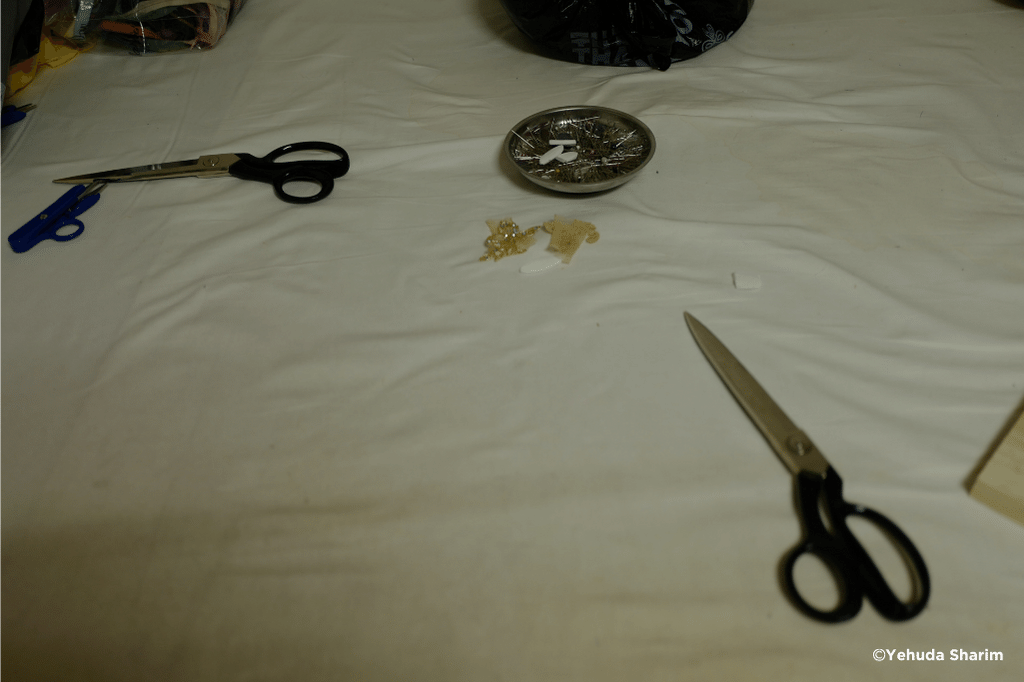

El cuerpo de la tijera/anatomy of a shear

Without it, how could you

Snip the hunger for revenge?

Your faith accompanies you everywhere,

Like the scissors you clip ribbons with,

Those blades that trim your solitude

That protect you like swords

Against the breath of alcoholic dragons.

The wasps of summer

Invading your studio garage

Could not stop you from staying there,

Fixing others’ too-long pants,

Listening to psychologists or lawyers or priests

Or scissors, making them sing,

As you praise, with each precise cleave,

The name of god you engraved onto each cutting edge

Las reparaciones

When it’s shredded, when it doesn’t fit, when it doesn’t exist, we go to her.

A surgeon of cotton, engineer of the bodice, velvet mechanic,

her eyes always skimming

damage to repair.

The needle between her lips.

The eye of the needle,

a gate of secrets.

Her listening also pricks, penetrates as she measures the bodies of tattered spirits that confess the size of their headache, the stench under the sheets, the times they escaped through a window, and were dragged home by parental wrath…

How high must the slip be? In another session, this question brings about bedlam, then compromise between mother and daughter as they negotiate dimensions for a prom dress. How high should the split be, a question evoking the murmurs and the secret places—la cocina—that should remain unseen and pristine. Cocina—another name for the vulva, another attempt to save what cannot ever be lost, but in this chamber of possibility, the costurera can be an accomplice. I’ve found someone to reproduce, if not myself, what I want to be. So yes, half an inch higher.

When it doesn’t exist, we go to her.

The world is in formation here, beside the mist of the machine, anytime someone finds themselves before her, arms up Christ-like, euphoric and shedding, like an exoskeleton, what doesn’t fit anymore.

History of my wardrobe

I build my wardrobe, my assemblage of basic colors and accents. I examine the labels, the instructions on how to wash. I prepare for the day, select an outfit, a ring for protection, a pair of shoes to meet with you afterwards. The shirt I wore to go to the doctor, to talk to lawyers, to kick my father out of the house. The shirt I wore the day we realized your diagnosis, the sheet my grandmother left as a gift, linen with the magenta blood of a murdered man she loved.

1994. That was the beginning of my parents’ credit cards. That marked the growth of my breasts. That was the start of our payments. It was not the beginning of desire: we had always wanted more. And more was coming to us. My parents signed their names on a credit application, while the mannequins stood, silent witnesses to an eternal loan. All my clothes were bought without money. Frustrated shoppers in line waited for their turn. We got home with comforters and catalogues thick like bibles. Browsing them, smiling models convinced me that happiness and new dresses go together.

I want denim shorts. Mom helped look for them in a now extinct department store. She can’t make them herself; denim is hard to sew on her machine. She is the same person that put together your shorts, years ago, before the factory was moved to Bangladesh. At the store, she examined the faulty stitches on some clothes I picked, her lips pressed in with an invisible needle between them. Absorbed, she was back in the factory, scrutinizing clothes unfit for us, inspecting the mistakes others had made in a hurry and in protest. Reading defective patterns and rushed afternoon hours along the hems before telling me this was not a good option: “mira, esta damaged.” Damaged was one of the first words she learned in the English language.

A dollar: for a dollar, what do we get? A trafficked parakeet, the elotes sold on the street, hidden from the police inside a stroller, fifteen minute parking. For a dollar, how much should we work? Roberto makes a dollar a day from selling chiclets, a colorful gum wrapped into squares on transparent plastic. He is five feet tall, has hazel eyes, dark skin and no teeth. He asked for my name once as I walked in Pacific Blvd. Remember this: we don’t know who feels hope when they see us. Years later, he sits on the asphalt, unable to walk. His calloused feet are now swollen. They don’t fit on his soiled, laceless tennis shoes.

Women hawk customers into the store—a dolar a dolar a dolar!!—their voices hoarse at the end of the day and at the end of their life. It’s a sale weekend, and all merchandise is outside on display. They lean on a rack full of clothes as mothers, fathers, grandmothers walk by. Choose: the lycra brown shirt with plastic diamonds, the ultra tight low cut blouse, the 9-11 commemorative t-shirt. Do they fit our bodies? Is it useless to think that the destiny of a pair of pants is linked to the destiny of the one who wears it, the one who made it? These clothes smell like new and soon will smell like someone’s perfume, the one we create with our secrets and secretions, always at a high cost.

Do not ask how my mother is doing

Do not ask how my mother is doing.

She took two buses to get to Target

to replace her shoes.

She went shopping for a phone

from people that will soon

be fired.

She’s home, waiting for someone

Sleeping in front of a television

that broadcasts

prolonged debates about the new members of the national soccer team the best exercises to lift your ass the real reasons of the divorce the the the the………

Do not ask how she’s doing.

She

sewing, trimming, ironing

for ABS and Splendid.

I ain’t going to sleep

until I finish this dress

me and my Jesus

will be up through the night.

they pay her 15 an hour

and good benefits.

The bus is

a motel

a mirror

to see our tired faces

in others’ visages,

where we

re-encounter our hands

and massage the unseen marks of overtime.

The bus is a phone booth

to discuss jail releases

and what’s for dinner.

The bus is

a cradle

That puts us all to sleep.

Do not ask me. If you do, you and I will have to sit with our cold drinks

And miss our deadlines.

I’ll have to visit her and give up my routine of absence in her street. I’ll have to call her, and hear her voice that does not lie, even if her words do.

Petition

Mirror of Justice

Desk of eternity

Street that leads me home

Street of public punishment

Tower of Retired Seniors

Angel of Public Transportation

Voice Mail of Absent Brothers

Lord of Corn and Mayonnaise

Queen of Bus Drivers

Designer of Security Uniforms

Scissors that cut through hard days

Gate of Barking Dogs

Burger specials to eat alone

Stitches that bind our skins together

Glasses not covered by insurance

Sewing Machine of Creation

Summons for Spanish-Speaking workers

with some English Ability

Frames with Missing Photographs

Reasons for my hard breathing

Cure for guilt

Happiness after new shoes

Wings of Courage

Coin purse of foul nickel and dimes

Protect those that walk at night to the store, clutching you tightly.

Arthritic hands holding coin purses

Protect those that sell oranges and wipe the table clear.

Public lamp of boulevards, illuminate those that walk beneath you at night—day-time belongs not to them, but to someone else.

***

This essay is part of the Care and Repair series, exploring topics and projects in conversation with the annual theme shared by UCHRI and the UC Humanities Network.

- (Sweeney, Megan. Mendings. Duke University Press, 2023.)

- (Sweeney, Megan. Mendings. Duke University Press, 2023.)

- This poem originally appeared in Cultural Weekly as one of the 2016 Jack Grapes Poetry Prize winners.