The Military Forms of Seaweed

by

“Holding Sway: Seaweeds and the Politics of Form” is a series of photo essays that channels a visual curiosity about seaweeds with considerations of militarization, gender, Indigenous sovereignty, extractive regimes, and climate change. Foundry guest editors Melody Jue and Maya Weeks invited participants to create or curate images that literally and figuratively “hold sway” in two senses: capturing the attention of an audience, or conveying a relationship of being in touch with seaweeds by holding their swaying botanical forms.

“…Adams’ photographs of ama maneuvered in rhythm with forces of nature, tradition, and a consuming, militarized gaze.”

In Japan, ama divers are said to have “long breath.” A diver with long breath can stay underwater for a minute or more, not once or twice, but at frequent intervals over many hours of repeated diving and surfacing. The longer an ama’s breath, the more sea-life she harvests. With little more than capacious breathing and expert technique, ama harvest seaweeds that also respire, absorbing and metabolizing nutrients directly from water. Algal cells convert the nutrients into polymers, or interconnected molecules that nourish the organism, giving seaweed its distinctively slimy texture. Holding onto the slippery and tangled seaweeds, much less harvesting great quantities, can be a daunting and messy task; but seaweed’s mucilaginous properties have long made it desirable and even profitable.

Red Gelidium, or tengusa—among the most valuable seaweeds sought by ama—form long molecular chains that are the basis of a translucent, gel-like material called agar. A remarkably mutable substance, agar has long been associated with Japanese culinary traditions.1 Later in the 19th century, agar was used as a growth medium for culturing bacteria in scientific laboratories, a precondition for producing medications, including penicillin. Although agar’s thermal and chemical stability allow it to be easily moved between kitchens and laboratories, agar is not—in a historical and political sense—neutral matter.

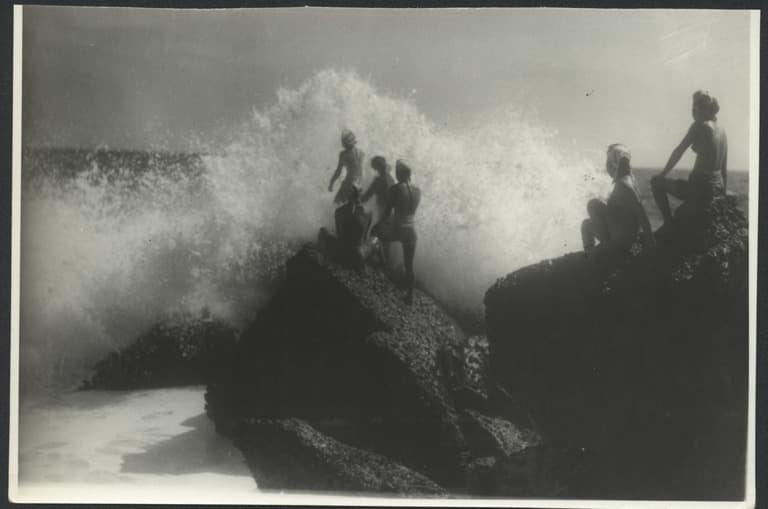

Agar-bearing Gelidium tend to thrive in rocky areas with steep underwater slopes, where rough surf conditions make diving difficult and dangerous. A circa 1947 photograph by a US military officer named Claude M. Adams shows a group of ama balanced on a sheer shoreline rock while powerful waves crash all around. With backs turned (perhaps defiantly) to the military occupier’s camera, they appear ready to harvest tengusa from the turbulent waters. Now held in the archives of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, dozens of photographs made and collected by Adams document the postwar Japanese seaweed industry and reveal how agar figured as a medium for the US military’s biopolitical power in the postwar occupation of Japan.

As early as 1942, the US military began preparing for long term occupations of Germany and Japan—a context that would shape Adams’ photography. In 1943, a Civilian Affairs Training School was launched at Stanford University to prepare soldiers in martial law, foreign languages, and culture. At Stanford, hundreds of military personnel, including Claude Adams, prepared to occupy Japan. Adams studied Japanese language, geography, history, customs, and cuisine, receiving mostly “B” grades on his final exams. In 1945 Adams was among the first military personnel to enter Japan under the command of General Headquarters for the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (GHQ SCAP). He was assigned to lead the Fisheries Division of GHQ SCAP’s Natural Resources Section (NRS) and tasked with jumpstarting commercial fisheries and the production of aquatic products in Japan. His mission focused on establishing an expeditious source of protein (whale) and the export of agar.

Japan was the world’s primary source for agar prior to World War II, but as the war unfolded, it became scarce in the West. In 1941, the US War Production Board designated agar as a “critical war material” and restricted its use to the war effort. Absent a sufficient stockpile of agar, Allied forces could be left without antibiotics and other medically necessary cellular cultures. The urgency of the shortage rose with the tide of war, and scientists at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography were charged with developing US domestic sources of algal war materials.2 Seaweed scientists and a dormant kelp-potash manufacturing industry in California helped—just in time—to avoid a wartime agar supply crisis, but fell far short of replacing pre-war supply levels.3 After the war, the US military’s appetite for agar and related marine products would continue to grow during the occupation of Japan.

Japanese agriculture and domestic manufacturing had come to a virtual halt by the time of the 1945 surrender. Food and fuel were desperately short throughout the country, and millions suffered from malnutrition. Allied nations were clamoring for economic reparations, and in response to the mounting political and economic crisis, GHQ SCAP’s attention turned (controversially) to the sea. Japan’s coastal waters were an obvious source of food and resources, yet the Japanese coastal stocks of fish had been decimated during the war and the nation’s fishing fleets banned from neighboring countries’ territorialized waters.4

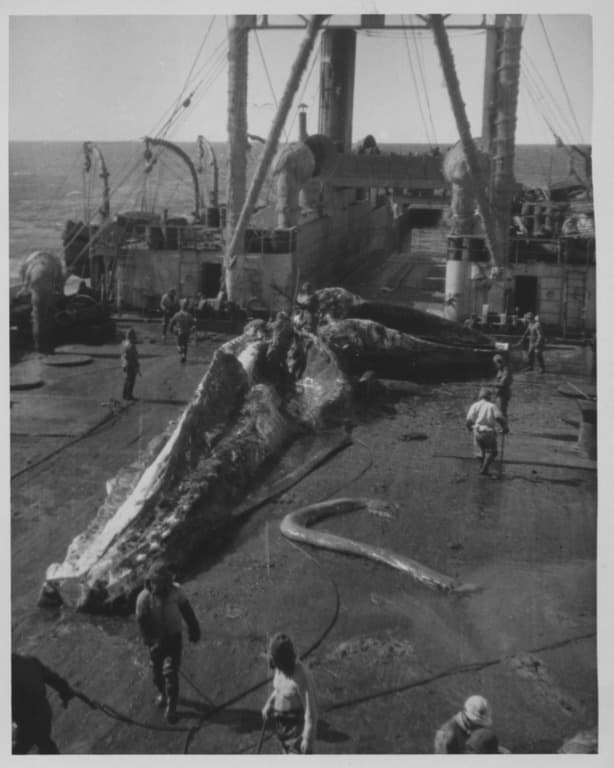

Seeking a quick fix to a compounding food crisis, the NRS initiated a program to expand Japanese whaling, for the first time, into the waters of Antarctica. The new whaling industry, however, was hindered by shortages of vessels and fishing gear. A former US oil tanker ship had to be refitted as a whaling factory. Although whale meat promised to eventually stock shelves and supply school cafeterias across Japan, its prospects for profitable export as a commodity remained dim. So, Adams and the NRS turned toward the intertidal zone for a solution, and the occupation became pre-occupied with seaweeds.

Compared to other fisheries, there were considerably fewer barriers to designating seaweed as a major commercial resource. Seaweeds were already central to Japanese cuisine, maritime cultural practices, and industries that remained largely intact throughout World War II. During the war, ama who traditionally worked in seasonally active cooperatives to harvest seaweeds and shellfish had been pressed into collecting vast amounts of kelp for the production of potash, an essential material for manufacturing gunpowder and fertilizers. In the postwar era, seaweed became critical to peacetime business and trade. By 1947 the agar industry had made a tremendous rebound, with nearly 600 agar producing plants operational in Japan. The first postwar Antarctic whaling expedition, by contrast, would not return with its desired catch until 1948.

“Adams channeled an occupier’s gaze that sought the satisfaction of touristic fantasies, and fixed on the exploitation of seaweed as a moldable material for the benefit of economic growth and US geopolitical interests.”

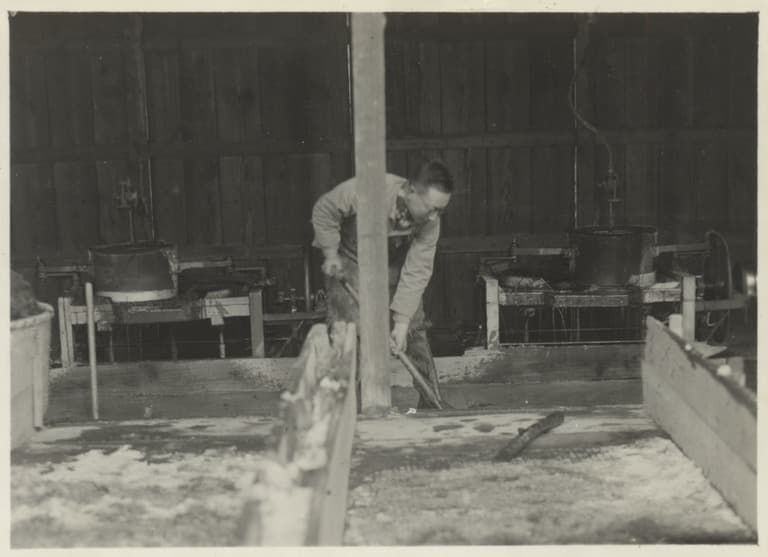

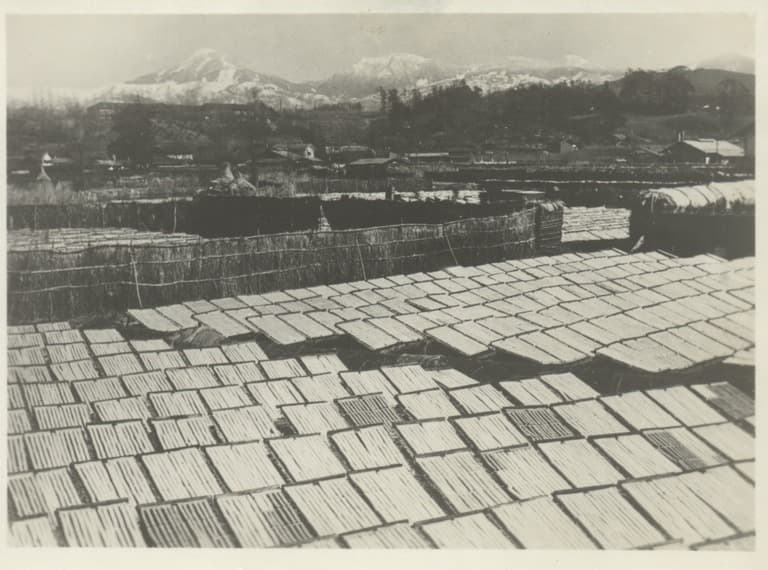

From 1946 to 1947, Adams toured Japan and surveyed the re-emergent agar industry, taking photographs that trace the seasonal patterns of agar production. The process typically began in late summer and fall, when lingering warm weather helped to dry out the Gelidium harvested by ama. Workers spread layers of the collected wet matter over raised platforms, carefully turning and slowly desiccating the seaweeds in choreography with the sun. Drying seaweeds is an initial step in the agar manufacturing process, during which rocks, shell, sand, and other matter are separated from the algal material. Once dried and cleaned, the seaweeds were brought inside a processing plant and boiled multiple times with water and small amounts of chemical additives, eventually thickening the Gelidium into a jelly. The coagulate was sifted, strained, and loaded into cooling tubs where the algae’s long-chain polymers underwent crystallization, forming into the ordered molecular structure that underwrites agar’s versatile materiality.

Adams tracked the semi-processed agar from the coast up to the mountains, where it was refined and dehydrated during winter months through cycles of freezing overnight and thawing during the day. His photographs from this stage of the process show workers wearing the winter caps and coats of the Imperial Japanese Army uniform while they remove the final product from wood-form molds and pack it for shipment. Much like Adams’ photographs of ama—maneuvered in rhythm with forces of nature, tradition, and a consuming, militarized gaze—the worker’s clothes and careful handling of agar bring into relief the coalescence of form between the residues of conflict and the production of premium seaweed product.5 Adams captured uniformed workers producing a cheap, abundant, and uniform commodity that suited GHP SCAP’s agenda for demilitarization and reindustrialization of the Japanese economy.6

As much as Adams’ images of agar and ama underscore GHQ SCAP’s maritime-industrial interests, the cache of photographs also features touristic snapshots that speak to the wider visual-cultural force of the occupation. One striking example is a full-length, self-portrait of Adams in Nagasaki at the atomic bomb detonation site. He stands in front of a large sign shaped like a broken arrow, emblazoned with Japanese characters, that marks the location of ground zero. The photograph is a souvenir of bombsite tourism, a rapidly developing industry that shuttled occupying soldiers to the militarily restricted sites of atomic destruction in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Adams’s visits to Nagasaki and other sites punctuate his tour of duty surveys of whaling and agar production. Their inclusion within the collection betrays a mutating relationship between militarism and tourism—what Teresia Teaiwa and others have called militourism—through which the Pacific was politically and environmentally reshaped in the postwar 20th century. The surge of militourism in occupied Japan was both documented and staged through photographic media—visual souvenirs, propaganda, and surveillance rendering a seamless amalgamation of military tours with leisure tourism.7 The Adams photographs reach much the same conclusion through a conflation of sightseeing and sea life.

Adams channeled an occupier’s gaze that sought the satisfaction of touristic fantasies, and fixed on the exploitation of seaweed as a moldable material for the benefit of economic growth and US geopolitical interests. In high demand for the supply of kitchens, factories, and laboratories the world over, agar seemed destined to be an essential ingredient for the postwar boom in biotechnological science and manufacturing.8 The force of a military occupation assured that seaweeds were commodified and transformed into growth media filling countless petri dishes. It is in this historical moment that algae began to take shape as a panacea for postwar macroeconomic and microscopic growth. A practically neutral substance that had been sent to war, agar continued to serve as a vital medium of mass (re)production. Ama’s long breath and Gelidium’s long chain polymers were thus mobilized in the making of a long twentieth century.

This photo essay is part of the Holding Sway: Seaweeds and the Politics of Form series, funded by UCHRI’s Recasting the Humanities: Foundry Guest Editorship grant.

Notes

- Agar’s discovery in Japan is typically described as an accidental invention by a 17th century innkeeper named Minoya Tarozaemon who threw some boiled seaweed outside on a cold winter night. After the rejected seaweed had frozen and thawed in the sun the next day, it was transformed into a reduced, spongy material. Minoya Tarozaemon boiled the stuff again and found that it congealed into a translucent, homogenous substance that could be easily shaped and molded and incorporated into dishes.

- Seaweed research on behalf of the US and Allied forces was led by C.K. Tseng, a Chinese marine scientist who worked at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography for the duration of the war. Tseng discovered local Gelidium substitutes for making laboratory-grade agar, and his research became the basis for local manufacture of 90% of the Allied wartime agar supply. See Norman W. Durrant, “The West Coast’s Seaweed Industry.”

- At its wartime peak, US domestic production of agar amounted to about 75 metric tons. By contrast, Japan’s pre-war annual export of agar had reached a total of 2,476 metric tons. See: Claude M. Adams, The Japanese Agar-Agar Industry.

- For an in-depth study of GHQ SCAP policies on fisheries during the occupation, and the role of Japanese fisheries in the emergence of the US Cold War posture in the Pacific region, see Harry N. Scheiber, Inter-Allied Conflicts and Ocean Law, 1945-1953: The Occupation Command’s Revival of Japanese Whaling and Fisheries.

- The agar worker’s surplus military attire indexes GHQ SCAP’s widespread conversion of former Japanese military assets into postwar factories, infrastructure, schools, housing, etc. The whaling ships that Adams oversaw are a similar case. Those flagships of the postwar whaling fleet were converted vessels that had been mainstays of the Japanese Imperial Navy.

- In a report detailing his close observation of the Japanese agar industry, Adams remarked that little to no mechanical equipment or expensive ingredients are used in the production process. He also suggested that this industry was resistant to mechanization or modernization because of a plentiful and low-wage labor supply. Adams, The Japanese Agar-Agar Industry.

- As a visitor to the restricted zone around Nagasaki in 1946, Adams could be considered an early adopter of militourism. Daniel Milne’s study of US soldiers’ touristic photographic practices during this period finds that “after the initial year or two of the Occupation, soldiers and other personnel increasingly took up photography as a pastime…an American abroad would appear ‘out-of-uniform’ without a camera.” Daniel Milne, “From Decoy to Cultural Mediator: The Changing Uses of Tourism in Allied Troop Education about Japan, 1945–1949.”

- A detailed account of agar’s material role in postwar biotechnical research and industry exceeds the scope of this essay and the contents of the Claude M. Adams photographs collection. For more on the historical development of biotech, see Hannah Landecker, Culturing Life: How Cells Became Technologies.