The University’s Two Bodies: Crip Labors of, and Beyond, Survival

by

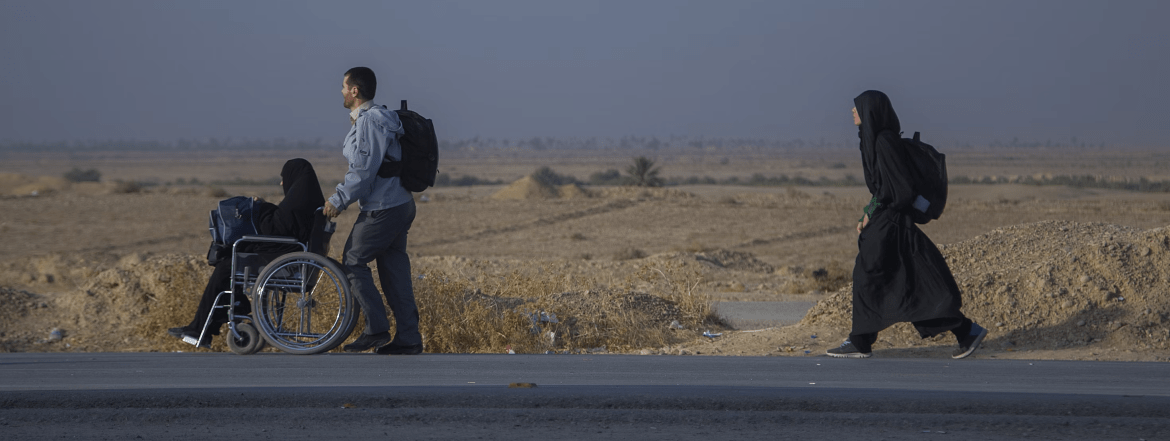

How do tensions between refuge and its refusals shape the nature of university labor, especially in light of recent upheavals? From the protest encampments on UC campuses to memory landscapes of Iran and trans activists in South America, UC PhD students in UCHRI’s 2023-24 professionalization program map the search for refuge from local to global.

To treat the question of disability justice as a question of addressing an accumulation of individual wrongs is to fail to grasp the atomizing logic by which the university, like society at large, constructs disability.

In his 1949 book The Concept of Mind, British philosopher Gilbert Ryle famously argued against what he called “the dogma of the Ghost in the Machine”—the view, associated with Descartes, that mind and body are distinct substances, with the mind “ensconced” in the machine of the body. Ryle thought this view resulted from a species of philosophical error he termed the category mistake, a blunder that occurs whenever something is placed in a logical category to which it does not, in fact, belong. Ryle’s attack on Cartesian dualism, like those of others, bears an intriguing resemblance to proposals in disability studies—including Margaret Price’s introduction of the term “bodymind”—aimed at unsettling the naïve separation of mind and matter, intellect and embodiment, in contemporary culture.1

Less obvious, however, is the connection between one of Ryle’s better-known illustrations of the phenomenon of the category mistake and questions that arise in thinking about the relation between disability, embodiment, labor, and the modern university. In the example in question, Ryle imagines someone unfamiliar with Oxford or Cambridge wandering either campus. They pass lecture halls and museums, libraries and offices. At the end of their tour, they ask, “But where is the University?” The visitor’s error, Ryle explains, lies in their thinking that the university itself must be another building, one they haven’t encountered yet. In failing to grasp that the university is an abstract organizational structure rather than an edifice or location, the visitor has made a paradigmatic category mistake.

Beyond illuminating the concept of the category mistake, Ryle’s story suggests a way of envisioning the intellectual activity of the university that obscures the disabled lives and labors that exist within and despite it—and without which it could not exist. To construe the organizing concept—and with it the core—of academic life as immaterial while acknowledging the physicality of its lesser components evokes a familiar, troubling hierarchy. That hierarchy places materiality and embodiment decidedly beneath mentality and intellection; it sees the world of matter as, at best, an instrument—a ladder to be kicked away whenever possible. The university and its signal product, knowledge, hover above the bodies that produce it.

***

In teasing out a thread between a seemingly innocuous idea at the center of Ryle’s example and a less-innocuous view about academic life and labor, I want to avoid saddling the philosopher with responsibility for the latter. My aim, as a disabled scholar of disability, is to underscore the pervasiveness of dematerialized conceptions of intellectual life and to point to some of the costs of these conceptions. For Ryle, this dematerialization is metaphysical and technical; to understand the concept of the university as abstract, I can imagine him insisting, has no moral or political implications on its own. My reading is not so much an assessment of Ryle as an annotation of the curious empirical adjacence of one feature of his argument to a view of academic culture that disserves the disabled, the chronically ill, and the neurodivergent.

We might call this view the “dogma of the disembodiment of intellectual life:” the idea that thought is only contingently, and regrettably, tied to living, breathing bodies. Everything done to maintain bodies that think is, according to this dogma, less valuable and interesting than their thoughts—which, it imagines, can be separated from their corporal origins. Routines of eating, sleeping, bathing, medicating, and caretaking it shunts offstage, into the shadows of the private sphere. Somatic needs and habits, it insists, fall outside the purview of intellectual life; they’re simply irrelevant. Quite a few scholarly projects besides Ryle’s have taken some version of Cartesianism as their target, but it would be misleading to imply that these endeavors, however ingenious, have succeeded in ejecting the ghost from the machine once and for all. The fact that all manner of dualisms must be rejected again and again suggests that what’s thought to have been banished still haunts us.

***

Thinking about disabled life and labor in academia through the lens of a specialist’s example may seem less effective than beginning with any of the countless real and material harms inflicted upon disabled students and academics by contemporary university culture. Why not start with a particular incident, then, or even with my own experiences of marginalization as a disabled, chronically ill, and neurodivergent doctoral student? Why not mention how, as I was writing this piece, a packet arrived in the mail to notify me that my university-sponsored health insurance had partially denied coverage for a recent hospital visit, potentially putting me in a life-changing amount of debt? Or, less spectacularly, why not discuss any of the hundreds of times I’ve attended a seminar or lecture in an unventilated, poorly-lit room while in chronic pain or withstanding a symptom flare—trying my best to play the role of an able-bodied, neurotypical graduate student while simultaneously attempting to process the conversation, take notes, and make my own contributions?

With each of these incidents, swaths of time and labor—two quantities already in short supply due to my chronic illnesses and disabilities—vanished from my life. But as major or banal as these events were for me, each represents only a sliver of the harms disabled graduate students experience with alarming regularity. From having to spend grocery money on medical bills to being ejected by their departments after seeking accommodations or protesting discrimination, the testimony of my disabled peers paints a dire picture. I could go on: there’s another version of this essay that derives from personal experience and population-level data the conclusions I’m driving at by conceptual means. It’s a version I’d never be able to finish and one that would be too long, in any case, to publish.

Part of what it is to be disabled in a capitalist society is to be deprived of a social role deemed adequately productive.

In recounting these incidents—mine and others’—the argument I’m attempting to construct threatens to dissolve into a litany of complaints. To be sure, the complaint, as Sara Ahmed reminds us, can serve as “a way of not being crushed”—a way to signal one’s willingness to fight. But to treat the question of disability justice as a question of addressing an accumulation of individual wrongs is to fail to grasp the atomizing logic by which the university, like society at large, constructs disability. Disability, according to this logic, is a property of individuals rather than a function of systems. To put things in terms of Ryle’s example, disability isn’t an organizing principle, but something one can point to, like a body interpreted as different. But despite disability’s publicness in this sense, this logic maintains that disability is at its core a private tragedy—a fact of human variation for which nothing and no one is to blame, least of all the non-disabled and the institutions they build.

Disabled thinkers have striven to show that this set of beliefs, this ideology, is false. They’ve demonstrated time and time again that systems and external structures, rather than facts about bodies and minds, are key producers of disability, even if these systems don’t explain every instance of disabling.2 The success of this counter-explanation is evidenced not only by the massive, field-forming impact the “social model” has had on Anglo-American disability studies in past decades, but by the model’s uptake in popular discourse. Without disputing the model’s central insight, it not only, in my view, goes too far—neglecting cases of disability that aren’t adequately explained by social phenomena alone, as others have long pointed out—but doesn’t go far enough in clarifying the economic bases of social disabling.3 Though the social realm is often construed as encompassing the interwoven dynamics of class, labor, and productivity, both disability theory and its popular counterparts have yet more ground to cover to understand this nexus.

***

Under capitalism, theorists including Tanja N. Aho have argued, a person’s ability to sell their labor is tied not only to their literal survival but to their social worth. Aho’s concept of labor-normativity refers to the capitalist conflation of economic value with moral, ethical, and political value: what follows when bodyminds are valued as citizens and neighbors only to the extent that they produce value on the market. This conflation seems to be yet another category error, one that Ryle himself could’ve used as an example of the concept.

But erroneous beliefs can have remarkable force, even when few confess to holding them. Aho, like the late disability theorist Marta Russell, persuasively argues for an understanding of disability that centers class. The power of these theorists’ work resides in its demonstrations of the dependence of the social category of disability on class violence. Part of what it is to be disabled in a capitalist society is to be deprived of a role deemed adequately productive. The trouble isn’t, of course, that the disabled don’t labor. On the contrary, disabled folks are some of the most resourceful and hard-working people I know—a fact I cite with trepidation, given its liability to appear to defend the disabled in labor-normativity’s terms. This becomes apparent when one learns, as I did when I became disabled, to discern the various kinds of labor the disabled must undertake, labor that exceeds what’s required of their able-bodied peers but which is often obscured by ableist norms or reinterpreted as non-labor. The trouble is rather that the social determinants of what counts as productive labor—that is, labor worth remunerating—exclude them. Even worse, this exclusion is intentional rather than incidental. Just as Marx understood the “sphere of pauperism” as a necessary condition of capitalism rather than its byproduct, Russell shows how cultural and governmental constructions of disability—even those embedded in the Americans with Disabilities Act—serve the interests of the ruling classes.4

In the culture of the contemporary research university, labor-normativity and the dogma of the disembodiment of intellectual life blend together. What results is a potent version of ableism that, as Jay Timothy Dolmage explains, not only demands able-bodiedness and neurotypicality but various forms of “hyperability”—a term that suggests that the performance of these abilities may be demanding even for those who consider themselves able-bodied and neurotypical.5 While a confluence of factors may explain this tendency—the ingrained competitiveness of academic settings, administrative austerity, shrinking job markets—the belief that intellectual life and labor are fundamentally immaterial only furthers it. It’s no accident that disability collective Sins Invalid lists anticapitalism as their third principle of disability justice on a list of ten, refuting labor-normativity directly with the assertion that “[o]ur worth is not dependent on what and how much we can produce.”6

In the culture of the contemporary research university, labor-normativity and the dogma of the disembodiment of intellectual life blend together.

Examining the academy’s emphasis on hyperability brings forward an important but overlooked contention made by disability theorists and critics: that ableist culture harms everyone, disabled and non-disabled alike—with the positive corollary that disability justice pertains to all bodies and minds.7 There are several reasons for this. First, despite the frequent treatment of disability as a binary identity—something one either has or lacks—disabilities, like abilities, exist on a spectrum. One might have a disability apparent to sighted people, or a disability that remains stable day after day, or a disability that meets both criteria. One might live with an illness that allows one to pass as able-bodied on some days while unable to get out of bed due to excruciating pain on others. The question of whether a particular bodymind “counts” as disabled admits shades of gray; self-determination, or what in Simi Linton’s terminology might be called the claiming of disability identity, may be the deciding factor. Second, an accident or illness may be all that stands between a given person and their identifying, or being identified as, disabled. Hyperability’s status as standard in the contemporary academy serves to reinforce the membership of all but the luckiest and most privileged academics in what contemporary sociologists refer to as the “precariat:” that mass of laborers perennially on the verge of material and social insecurity.8

***

In touching on a few recent incidents in which my own disabilities and illnesses led to my clashing with institutions, I meant to highlight how disabled graduate students and academics are faced with various additional “taxes”—to generalize Annie Lowrey’s discussion of the “time tax”—of time, labor, effort, and suffering. We pay these “disability taxes” as a matter of survival. We may pay them in a monetary sense, by ultimately earning less than our non-disabled peers despite needing substantially more funds simply to reach their standard of living. And we may pay them by a variety of maneuvers—seeking accommodations and resources, coping, masking, and too many others to list here—that amount to what I want to call crip labor, a term I’ll elaborate on in what follows.9 Because these labors aren’t deemed intellectual or remunerable, however, they count for nothing in the university’s tallying of productivity. This happens despite the fact that these labors often require hyperabilities of their own.

But the claim I want to put forward is not just that disabled graduate students and academics must work overtime to survive in the contemporary university. Nor is the claim that, in paying what I’ve referred to as “disability taxes,” labor-normativity ensures that the disabled effectively pay twice: once when they do the work, spend the time and money, and undergo pain for the privilege of simply sharing a classroom with their non-disabled peers, and again when this labor goes unacknowledged or even disparaged. Following the work of Russell and others, the suggestion is further that the situation of the disabled in academia, seen through the lenses of labor and value, illuminates the situation of the precariat, including academic workers more generally. The situations that disabled students, faculty, and staff face are not niche issues, not “minority” concerns. They intersect not only with concerns about racism, sexism, and classism in the academy, but with the concerns raised by those who, understanding themselves as non-disabled, think they have no direct investment (a term I use with consideration) in disability justice.

The situation of the disabled in academia… illuminates the situation of the precariat, including academic workers more generally.

“The business of American education has always been business,” writes Elizabeth Tandy Shermer. It may have, but more so now than ever. As Wendy Brown argues in Undoing the Demos, higher education has transitioned from the attempt to cultivate an aristocracy, through an egalitarian phase, and into a neoliberal phase obsessed with the production of “human capital.” Those employed or studying in universities operating on corporate management principles find themselves on the inside of what Sandy Sufian terms the “regime of productivity,” an ideological counterpart to labor-normativity.10 Because both the disabled and non-disabled alike are valued in terms of their productivity in academia—administratively, but also at the level of academic culture itself—the situation of disabled academics is an image of what, in principle, this regime produces at its most cruel. This image reveals a logic that governs all academic workers, a logic that remains fundamentally economic despite its overtures to humanist values. The dogma of the disembodiment of intellectual life not only obscures the significance of the interplay of mental and physical life for what we might consider “strictly” intellectual labor. It obscures, too, the economic prerogatives of this erased physicality—prerogatives that affect, however much we wish this weren’t so, what the life of the mind looks like when not merely dreamt about but lived.

***

Disability’s social consequences might help to explain why only 13.4% of surveyed American adults identified themselves as disabled to the US Census Bureau in 2022 despite the CDC’s estimation that at least 27.8% of American adults have some type of disability.11 When merely being perceived as disabled exacts high costs, strategic underidentification and denial are predictable outcomes. This is all the more so in contemporary academic culture, which, as Dolmage notes, stigmatizes anything perceived as weak. Consider that while the National Center for College Students with Disabilities reportedly estimates that only four percent of American faculty members are disabled—hardly proportional to the near-third of disabled Americans reported by the CDC—only 1.5% of faculty at my university, UC Berkeley, identified as disabled in 2016. Even if genuine underrepresentation in part explains these numbers, it’s worth asking what might be motivating some faculty to disavow or mask their disabilities.

When merely being perceived as disabled exacts high costs, strategic underidentification and denial are predictable outcomes.

At times a practical necessity, masking—working to appear non-disabled, non-ill, and neurotypical—is a form of what I want to call, with others, crip labor.12 Following queer theory’s reclamation and verbing of the term “queer,” the word “crip” has several meanings in contemporary disability studies and critique. Though it can function like a noun or proper noun, it most often appears in disability theory as an adjective or verb: theories and people can be crip, and theories and people can crip their objects of inquiry. While not uncontroversial, and while differing in other ways from the term “queer,” crip has become a de facto part of the field’s vocabulary.13 In their verbal senses, both queering and cripping, according to Carrie Sandahl, work as forms of “wry critique” that reveal the arbitrariness of distinctions between normalcy and deviance, nuancing objects, institutions, ideas, and norms that culture situates clearly on either side of that divide. Along with the suggestion that we think of the intersection of disability and class as a bellwether for issues of labor in general, I want to suggest that crip labor can include not just the extra work with which the academy burdens its disabled members, but any necessary labor of care for self or others performed by a member of the underclass. Crip labor, then, is a form of social reproduction, part of the labor workers must perform to ensure that they can continue to labor in the future.14 Specifying this labor as crip picks out the work of social reproduction that takes place in a context where neither one’s existence nor survival as a bodymind is valued or guaranteed.

This suggestion follows Robert McRuer’s search for a critical space where we might counterintuitively imagine the intersection of cripness and nondisability. Academic crip labor, in my view, is not just taking time you don’t have to apply for accommodations or to visit a doctor; it’s what transpires among a group of friends sharing notes with each other when one is sick or has to miss class to care for an aging parent. It’s not only the labor of masking one’s disability, or of confronting unsanitary or inaccessible classrooms; it’s the labor entailed by the refusal to perform ability, whether on principle or because it simply isn’t possible any longer. It may be the labor of deliberating about whether one can afford to answer a university survey about disability truthfully, or the labor of advocating for COVID-safe policies to protect one’s immunocompromised peers. If, following Alison Kafer, one of the most powerful aspects of the term crip is its expansiveness, perhaps this suggestion can be received in that spirit: not as decentering disabled labor, but as emphasizing how disabled labor shines a light on the precariousness of all labor performed in the neoliberal university.

Crip labor can include not just the extra work with which the academy burdens its disabled members, but any necessary labor of care for self or others performed by a member of the underclass.

The examples in the preceding paragraph highlight the ways that crip labor, taking the everyday labor of the disabled as its model, can be used to describe the work that members of the academy’s precariat—grad students, adjuncts, those without security of employment—must perform to survive and stay employed, whether these efforts are recognized by the university or not. But crip labor goes beyond survival when it attempts to imagine and actualize embodied flourishing—flourishing that accounts for the desires as well as needs of disabled and non-disabled bodyminds, and which may stand in tension with commodified ideals of “wellness” and the medical establishment’s criteria of health. The difficulty of imagining such flourishing for each of the academy’s disabled members or would-be members attests to the extent of labor-normativity’s embeddedness. From the hope-impoverished present, what else could this flourishing look like but that of the hyperabled academic “overcoming” disability, even if crip labor served as their engine?

***

In 1957, the historian Ernst Kantorowicz published The King’s Two Bodies, an excavation of the theological roots of certain European conceptions of monarchic rule. Central to Kantorowicz’s argument was the titular fiction of the king’s two bodies, elaborated in a collection of reports written by the English lawyer Sir Edmund Plowden in the late Tudor period. Abstracting from the historical context of Kantorowicz’s magnum opus—which Giorgio Agamben would later describe as “one of our century’s great critical texts on the state and techniques of power”—this fiction, like Ryle’s example of the category mistake, provides a useful heuristic for thinking about institutions and ideology. The monarch’s two bodies are the “Body natural” and the “Body politic,” with the former “subject to all Infirmities that come by Nature or Accident, to the Imbecility of Infancy or old Age, and to the like Defects that happen to the natural Bodies of other People.”15 In going to great lengths to spell out the ways in which the king’s body, like those of lesser mortals, might experience variance and imperfection, Plowden situates disability as characteristic of human embodiment. Mysteriously, the body politic purifies the king’s human body, with which it forms an indivisible whole.16

Setting aside the doctrine’s more esoteric details, parallels emerge between the fiction of the king’s two bodies and the view of intellectual life I associated with Ryle’s example. Both locate institutional power in immaterial constructions that exceed the particular living, breathing bodies that circulate in them. The nature of the relationship between the immaterial and material differs in each case: if the mystical body politic negates the king’s private disabilities in order to guarantee the continuity of the state, the abstracted university ignores and conceals the bodily existences of its members in order to sustain what an emphasis on hyperability allows it to produce. In both cases, however, absent theological explanations, it’s the bodyminds that live and move within these institutions—whether they belong to monarchs, politicians, or students—that sustain the edifices, abstract or otherwise, that loom over them.

One might, however, find something liberatory in the purported indivisibility of these two bodies—the university as immaterial, on the one hand, and the embodied labor that sustains it. If the indivisibility of the king’s two bodies served the goals of sovereign power and institutional longevity, the indivisibility of the university’s two bodies, in an optimistic retelling, might serve instead as a reminder of the indispensability of embodied life for intellectual labor. Might it be possible to make this counter-narrative-in-miniature the dominant narrative, so that academic culture not only welcomes but includes in its self-conception bodies and minds besides those of the hyperabled? Might it be possible for the university to acknowledge and even compensate the crip labors that its members—some more than others—must perform? More radically, can we imagine the university as a space where intellectual activity remains open-ended and ongoing, rather than production-oriented?17

I hope so. But from my standpoint as a disabled graduate student, things seem grim. Indeed, one of the reasons crip labor, as I imagine it, takes so many forms—from coping and survival to, perhaps, flourishing—is due to the felt impossibility of directly breaking out of the contemporary academy’s regime of productivity. If, as has been said, it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism, it seems easier to imagine the abolition of the university altogether than a form of it that instantiates disability justice.18 As Dolmage points out, a typical response to claims about the academy’s ableism is concession: the quietistic acceptance of ableism as the consequence of an otherwise-desirable elitism.19 Unchallenged by images of how things might be otherwise, this quietism—a strategy for coping with the reality of injustice—prevents would-be allies from grasping the powerful questions that disability studies poses about the project of the university.

It’s more necessary than ever, I believe, to supplement critique with this imaginative work. And as we do so, it’s worth noting that the university may in fact be a crucial site for disability reform, rather than a contingent or special-interest one. The history of the university is intertwined with that of the asylum; both institutions have served as tools of social management, as sites of the development and proliferation of eugenics, and as organs for the manufacture of orderly, productive citizens at opposite ends of the spectrum of perceived ability.20 The eugenic legacy of the Western university, and the outsized influence this legacy exerts on contemporary concepts of disability, suggests that the university is not only a historically appropriate location from which to reframe our understandings of intellectual and embodied labor, but a socially efficacious one—a site where new generations can begin to undo the catastrophic effects of this history.21

Can we imagine the university as a space where intellectual activity remains open-ended and ongoing, rather than oriented towards production?

This reframing will require flexibility of a sort not often ascribed to disabled bodyminds by ableist culture. In forcing the university to face up to the bodies that make it what it is, acknowledging that disability endlessly “sprawls, shapeshifts, [and] resists definition even as institutions continually seek to define it” will serve as an antidote to a rigidified, constraining picture of disability and its possible futures. We’ll have to think beyond institutional “inclusionism”—the toleration of difference so long as it doesn’t demand too much change—and toward what Mia Mingus describes as liberatory access, or access in the service of “justice, liberation and interdependence.”22 We can only hope to substitute the damaging image of intellectual life that we’ve inherited with a broader, more open landscape—one where a community of embodied intellects works to ensure that living and thinking beyond survival is not only imaginable, but obtainable, for everyone.

This publication was supported in part by the University of California Office of the President MRPI funding M22PS5863. UCHRI thanks editor and writer Michelle Chihara for her developmental work with the series contributors.

Notes

- Sami Schalk, Bodyminds Reimagined: (Dis)Ability, Race, and Gender in Black Women’s Speculative Fiction (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018), 5; Abby Wilkerson, “Embodiment,” in Keywords for Disability Studies, ed. Rachel Adams, Benjamin Reiss, and David Serlin (New York, NY: New York University Press, 2015), 67–70; Margaret Price, “The Bodymind Problem and the Possibilities of Pain,” Hypatia 30, no. 1 (2015): 268–84.

- Michael Oliver, The Politics of Disablement, Critical Texts in Social Work and the Welfare State (Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan Education, 1990); Dan Goodley, Dis/Ability Studies: Theorising Disablism and Ableism (London, UK: Routledge, 2014).

- Susan Wendell, “Unhealthy Disabled: Treating Chronic Illnesses as Disabilities,” Hypatia 16, no. 4 (2001): 17–33.

- Marta Russell, “The New Reserve Army of Labor?,” in Capitalism & Disability: Selected Writings, by Marta Russell, ed. Keith Rosenthal (Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books, 2019), 23–32; Karl Marx, Capital, trans. Ben Fowkes, vol. 1 (London, UK: Penguin Books, 1990), 797.

- Jay Timothy Dolmage, Academic Ableism: Disability and Higher Education (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2017), 70.

- Sins Invalid, Skin, Tooth, and Bone: The Basis of Movement Is Our People, 2nd ed. (Berkeley, CA, 2019), 24.

- Sins Invalid, 68.

- Guy Standing, The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class (New York, NY: Bloomsbury Academic, 2011), vii.

- Elisabeth Kutscher, Lauren Naples, and Maxine Freund, “Students with Disabilities and Post-College Employment: How Much Do We Know?” (National Center for College Students with Disabilities, February 2019); Nanette Goodman et al., “The Extra Costs of Living with a Disability in the U.S. — Resetting the Policy Table” (National Disability Institute, October 2020).

- Sandy Sufian, “The Prejudicial Logic of Productivity,” Inside Higher Ed, April 11, 2023; Marc Bousquet, How the University Works: Higher Education and the Low-Wage Nation, Cultural Front (New York, NY: New York University Press, 2008).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Disability Impacts All of Us: Infographic” (Disability and Health Data System (DHDS), July 2024); U.S. Census Bureau, “Disability Characteristics,” 2022, ACS 1-Year Estimates Subject Tables, Table S1810, American Community Survey.

- For a recent use of the term, see J. Logan Smilges, Crip Negativity (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2023).

- Mark Sherry, “Crip Politics? Just … No,” The Feminist Wire, accessed June 27, 2024; Price, “The Bodymind Problem and the Possibilities of Pain.”

- Karl Marx, Capital, trans. Ben Fowkes, vol. 1 (London, UK: Penguin Books, 1990), 274–76.

- Edmund Plowden, cited in Ernst H. Kantorowicz, The King’s Two Bodies: A Study in Mediaeval Political Theology, Princeton Classics (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016), 9.

- Plowden, cited in Kantorowicz, 9.

- David I. Backer and Tyson E. Lewis, “The Studious University,” Cultural Politics 11, no. 3 (November 1, 2015): 329–45.

- Fredric Jameson and Slavoj Žižek, quoted in Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? (Portland, OR: Zero Books, 2009), 2.

- Dolmage, Academic Ableism, 39.

- Dolmage, 3–19.

- Dolmage, 11–12.

- David T. Mitchell and Sharon L. Snyder, The Biopolitics of Disability: Neoliberalism, Ablenationalism, and Peripheral Embodiment, Corporealities (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2015), 14; Mia Mingus, “Access Intimacy, Interdependence and Disability Justice,” Leaving Evidence (blog), April 12, 2017.