Tianquiztli: Reflections on Border Markets in Times of Crisis

by

Humanizing Acts is a series of essays and artworks that examines the impact of COVID-19 on the U.S.-Mexico borderlands. Each contributor writes about the ethical quandaries of conducting research at the border, living amidst the vulnerability and violence of pandemic times, and navigating complex interpersonal relationships and responsibilities. The scholars and artists share compassionate stories of people, including friends, loved ones, and neighbors alike, ultimately asking: How can academic research be a humanizing act?

En todas partes y en ninguna a la vez… (El Cielo del Sobreruedas) [Excerpt], 2021. Courtesy of Cognate Collective.

When we look up at the constellation commonly known as the Pleiades or the “Seven Sisters,” we see what our ancestors saw: a cluster of stars gathered in close proximity, as if preparing to exchange with one another. In Nahuatl, this constellation shares its name with the term used to refer to marketplaces: tianquiztli, meaning the “place of gathering.” Open-air markets throughout Mexico and Central America are known as tianguis today because they trace their etymological origins to this term, to this semantic bridge linking the celestial and the terrestrial, the symbolic and the material, and the temporality of the cosmic with the present-ness of the everyday.

Our research and artistic production within sobreruedas in Tijuana, tianguis in Mexico City, and swap meets in Southern California is inspired by this conception of marketplaces as sites of convergence and connection. Beyond their function as places to gather for commercial/economic exchange, such markets facilitate forms of cultural and social exchange that are especially vital for marginalized/subaltern communities residing within border zones—where inclusion/exclusion, belonging/alienation, movement/confinement, and agency/restriction are contested as both historical traumas and present-day struggles. Within such terrains, we argue that markets be understood not just as a places to source objects and services, but as a web of relationships—between individuals and the spaces they inhabit—mediated through objects. The web of relationships we witness in markets incubates models of transborder relationality, or post-national citizenship aligned with what Homi Bhabha calls a vernacular cosmopolitanism, a socio-cultural position that “takes its tone from the everyday existential exigencies and political interests of displaced and diasporic people” and “manifests a political will to establish neighborly relations in traumatic and challenging conditions.”

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, spending time and developing projects with communities in/around marketplaces became unfeasible for us. As a result, our practice was forced to shift. We turned to exploring the history of markets—which is how we came to consider the etymology of the tianguis. This new line of research has shaped our subsequent thinking about the nearness and adjacency that public markets offer us, the way they humanize modes of exchange with/in communities that are confronting dehumanizing social conditions. In this moment, emerging from a context of mass death and social isolation, such spaces and opportunities to gather become nothing short of an ancestral blessing.

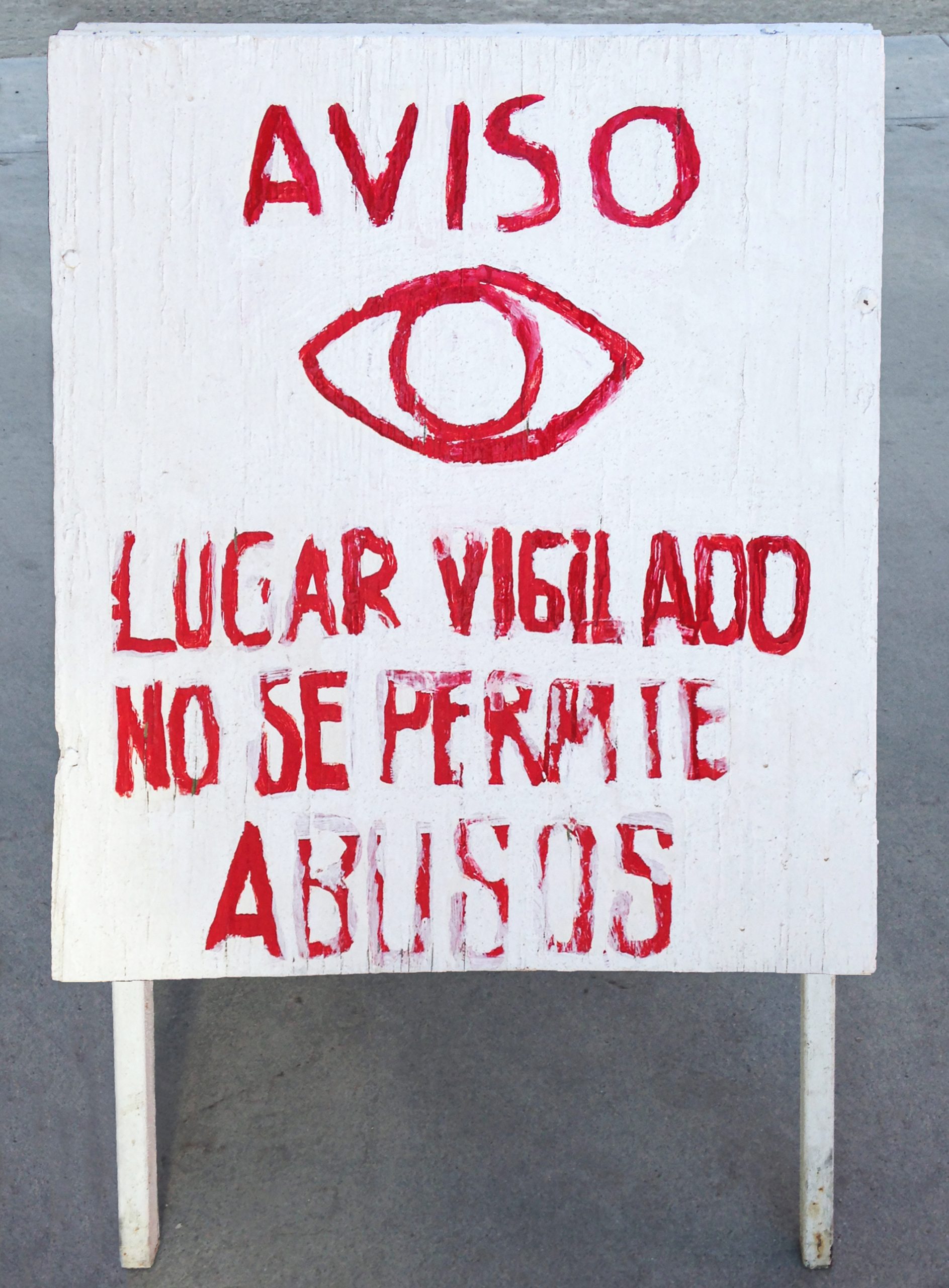

Markets were the first public place that we returned to after social distancing and quarantining for much of 2020 and 2021. We emerged from our home with excitement to the Spring Valley Swap Meet and the National City Swap Meet in San Diego, to the Santa Fe Springs Swap Meet in Los Angeles county, and of course, to our beloved Mercado Sobreruedas Pancho Villa in Tijuana. Gathered here are selected audio/visual/textual portraits resulting from these visits. They document, honor, and archive the politics, affects, individuals, and items that compose these spaces of gathering: spaces which have endured through occupations, displacements, and pandemics, spaces that become portals back to ourselves, to our history, and the fundamental human practice of exchange.

The visual components of this text capture the textures of physical, social, and economic infrastructures that amount to the aesthetics of public markets. For more than a decade we have looked to the (site)specific ways that markets allow us to contend with the macropolitical: breaking down monolithic metanarratives around borders, migration, capital, labor, and the agency of (im)migrant communities. In these textured layers of materiality, sound, and affect, we can see and feel the ways that immigrant, working class people challenge dehumanizing conditions that the U.S./Mexico border imposes upon families and communities. Crises like the COVID-19 pandemic, and the way this public health emergency was instrumentalized to further sow division (like by implementing Title 42 to criminalize migrant communities and deny them the right to move across the border in search of asylum,) have led to our alienation from one another. We find ourselves called to and inspired by the aesthetic and (nascent) political forms of resistance and resilience present within border marketplaces, recognizing that it as at the seams where we must learn how to sew ourselves back together.

I.

“¿Han ido al sobres?”

We pose the question on a Zoom call to our friend Christian Zúñiga, a Tijuana-based researcher, educator and artist. It is the height of the pandemic. He says no because he and his partner, artist and writer Mariana Chavez, are taking precautions with their baby, who was born in the Spring of 2020.

Together we reminisce about visiting mercados sobreruedas or “markets on-wheels,” itinerant markets which set up on different days of the week in varying neighborhoods throughout the city of Tijuana. We talk about how we’re hoping that one day we will be able to once again look through records, peruse toys, eat tacos, and have ice cream on a Sunday afternoon.

In the “sobres” (an abbreviation of sobreruedas) you can find everything from fresh produce to electronics, from home furnishings to vintage records, toys, and collectibles, and all kinds of second-hand items sourced across the border from thrift stores, swap meets, and yard sales in San Diego and other Southern CA cities. Alongside these items traditional street foods like birria, carnitas, and sopes are prepared in all manner of regionally specific styles, to cater to patrons who have migrated north, “al norte,” to the border city of Tijuana from the interior of Mexico. Increasingly, you also see international foods from throughout Latin America, like Salvadoran pupusas and Haitian chicken, a result of recent waves of migration from the global south to the border. Markets in our local border region continue to serve as a landing mat for those far from home, as they create new enclaves of belonging in our region while awaiting legislative decisions that will determine their fates—a limbo that many migrants have had to endure because of cruel and unjust restrictions imposed around seeking asylum as a result of the implementation of Title 42 at the onset of the pandemic. In recent months, community members have shared that they have even seen the emergence of culturally specific markets within markets that sell products from the Caribbean and Central and South America. The resulting brunch-time fusion of dishes and flavors made possible by markets is something that we and the other visitors to the sobres relish and look forward to, making the fugitivity of migrant gestures palpable and tastable as part of the everyday.

Christian speaks about the mercado sobreruedas as a hybrid of two other market forms: the tianguis, which has Mexica/Aztec origins, and swap meets in Southern California. In our work it has been important to explore the similarities between public markets in Southern California and Northern Baja California as well as to consider the differences in organization, how they are activated and used by their constituent communities, and the different forms of agencies which emerge as a result of such distinctions. We have undertaken this work with students and community collaborators, and invited shoppers and visitors to the markets to participate in the workshops, performances, and events that we have facilitated in these different marketplaces.

Through this work, we have witnessed the critical role markets play as sites to (re)connect with one another, with one’s (sub)culture, and with hometowns near and far. For (im)migrant families who refuse to assimilate, like our own, such spaces are vital, as they facilitate (re)building a sense of self, a sense of community, and a sense of home.

In 2020 in an effort to mitigate the spread of COVID-19, the municipal government limited the number of stalls that could remain operational to those selling “essential” goods and services: fruits and vegetables, tools and hardware, food products and services, natural medicines, groceries, cleaning products, diapers, cellphones, and pet food.

Unsurprisingly, the announcement that the sobreruedas would be restricted was met with resistance not just from vendors whose livelihoods depend on selling there, but from shoppers who frequent these markets. During the early days of the pandemic, shoppers and vendors were depicted as careless, stubborn individuals who did not care about the health of their community. Reports framed their use of public space as frivolous, often using classist language to insinuate that these spaces were not only “nonessential,” but a public health menace of the proletariat.

As the pandemic progressed and we learned more about the nature of viral transmission, these discourses in relation to the sobreruedas were reassessed, given their outdoor setting, the fact that they would travel directly to communities and neighborhoods (decreasing the need for people to leave their home/immediate surroundings in search of groceries and basic needs), the access that they provided to essential goods and services at prices that were relatively affordable, as well as the fact that they allowed for maintaining community morale during this moment of public health crisis.

Today—in our collective emergence from social distancing and isolation—more people are returning to marketplaces to gather, to find themselves among others once again. As we’ve rejoined our communities in returning to markets after the collective experience of mass trauma and death that is the COVID-19 pandemic, we’ve experienced joy and exhilaration as we share space with others. And, as we’ve experienced so frequently in this time of transition from life circumscribed by conscious confinement and social distance to life lived in conscious proximity to others again, we also find ourselves reflecting on the fact that we should not take such opportunities for collective gathering and social exchange for granted.

The sobres, the swap meet, and the tianguis are made up of physical and social infrastructure. The way that forms of materiality are displayed, stewarded, and used as pretext of sociality, dialogue, and connection by people is what makes these spaces so special and unlike commercial spaces of malls and big box stores. The most palpable loss during the COVID-19 pandemic has been the loss of individuals who were fixtures of markets: some who were innovators of display, others who had keen curatorial eyes or a penchant for storytelling, or who were perhaps the only remaining vendor that sold a certain tool, variety of fruit, or genre of music. Some of these vendors and regular visitors to the market were on the verge of retirement and decided to sell their inventory and take a slightly earlier leave from their often decades-long job. Others succumbed to the virus, or to other ailments, during our collective retreat from public life. So we found ourselves returning to contexts that were familiar and bubbling with energy and excitement, while also holding deep melancholy, longing, and a sense of nostalgia for how and with whom we had experienced these spaces before. “The man that sold the oldies CDs passed away,” comments the young man at the front gate of the National City Swap Meet; “I don’t know if it was COVID or if he was sick for a long time, but it’s weird not to hear his stand anymore.” As we walk through the sobreruedas Pancho Villa on a Sunday afternoon, we learn that a respected tacos de canasta vendor has retired from her business. “Ya te chingaste,” says a middle aged man teasing a disappointed friend who walks the market with a caguama disguised (but not really) in a paper bag that would have contained his tender basket-taco lunch.

We cannot help but think of the grief that is invisible and accumulated in these crowds of people, the loss of sounds, tastes, texts, greetings, and rituals that amount to a loss of people and many elders. Yet we tell the story of the man and his music, we hope that the recipe of the tacos is preserved somewhere, and we continue to gather to keep their memory alive, to sustain what is, and to welcome what is yet to come.

II.

After nearly a decade of artistic production around and within public markets in the U.S./Mexico border region, arriving at the Tianguis de la Lagunilla in Mexico City in the summer of 2022 felt like a pilgrimage. It is one of the oldest markets in Mexico and Latin America more broadly, setting up continuously in one form or another for at least the last 400 years. We go there interested in the spatial and speculative connections it has to the great Mercado de Tlatelolco, a central hub for exchange of the Mexica/Aztec empire.

The market feels incredibly familiar even though we’ve never been there. It is a space that we feel grateful to and that we’ve known as a kind of foundational space to our life practice, before it ever became central to our artistic practice.

Venimos a dominguear—”we came to Sunday.” Mexico City is hot, in the middle of a heat wave, and the air smells like humidity, traffic, ripe fruit, and grilled meat—like street market deliciousness. We’re both sweating profusely under our face-coverings which about half of the people in the market have on.

We squeeze through pasillos (aisles) of the mercado, sometimes inches from other people with the anonymous intimacy that bodies take on in public spaces where we are squished together by circumstance. It feels precarious and frankly anxiety-inducing after years of isolation and concerted distance. At the next opportunity we seek out parts of the market that feel more open, airy, but are still characterized by a visual environment full of signage, merchandise, people, carts, and infrastructure, all moving in a choreography of proximity that makes exchange possible.

III.

Later that summer, we find ourselves in the National City Swap Meet, on a day warm enough that misshapen squiggle-mirages blur patches into the asphalt pavement of the market grounds. It is just after midday; most visitors came early to evade the heat, so vendors are beginning to break down their stalls. We are among the few customers that remain.

We look through the bolts of fabric of numerous textile vendors, then head to the secondhand section of the market looking for mirrors for a project we will undertake in this very swap meet in about a month’s time. As we dig through a box—which contains a dirty blue care bear, a dish rack, some fancy dinner napkins, a treat puzzle for cats, lots of boxes of paper clips, a vibrator, shoes that are probably too worn to be resold, and numerous other oddities—the man in charge of the stall yells from the back: “¡Ya vamonos! ¡Que pinche calor!” He lets us all know that everything on the table beside us—mostly clothing and home goods like blankets, curtains and pillows—is now free. He would rather not pack everything up and take it back to Tijuana, he says it’s too much effort. He is jubilant in this announcement, like he knows how delighted this makes all the patrons. Immediately we gather around the table and begin hunting for our treasures.

A pair of sisters who look in their 70s ask us for help finding the matching pair of pants for a silky pajama top, as they begin to hold items up to us because they say that we’re about the size of their grandchildren. They ask us about the camera we’re carrying—a medium format camera from the 80s—and we tell them that we’re artists and that we make work in and about markets. They congratulate us and tell us how they’ve been coming to the National City Swap Meet for decades, how it used to be a drive-in, and how they remember coming with their young children. Now they visit every now and then for the deals, and to get exercise, since they live within walking distance. They are both wearing impeccably clean tenis—kept pristine in the fashion of Latinx elders of our grandparents’ generation.

“Have you seen that this is where the Amazon vans sleep?” one of them asks us, with a kind of suspicion and foreboding in her voice. “The admission used to be 25 cents, it’s a dollar now! And now the vans. A ver que pasa,” she says with a sigh and a certain degree of resignation.

We say goodbye to them. “Que dios los bendiga, muchachos,” they say with a smile, but without looking up from their shopping. With their blessing we walk to our car, carrying our bounty.

This essay is part of the series Humanizing Acts: Resisting the Historical Erasures of the COVID-19 Pandemic across the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands, funded by UCHRI’s Recasting the Humanities: Foundry Guest Editorship grant. Listen to the collaborative podcast, in which series contributors discuss the gifts of resisting the historical erasure of the COVID-19 pandemic with community and research.

This publication was partially funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.