Time to Go South: Memory Work and Political Dialogues from South America

by

How do tensions between refuge and its refusals shape the nature of university labor, especially in light of recent upheavals? From the protest encampments on UC campuses to memory landscapes of Iran and trans activists in South America, UC PhD students in UCHRI’s 2023-24 professionalization program map the search for refuge from local to global.

Archives and History are not neutral devices.

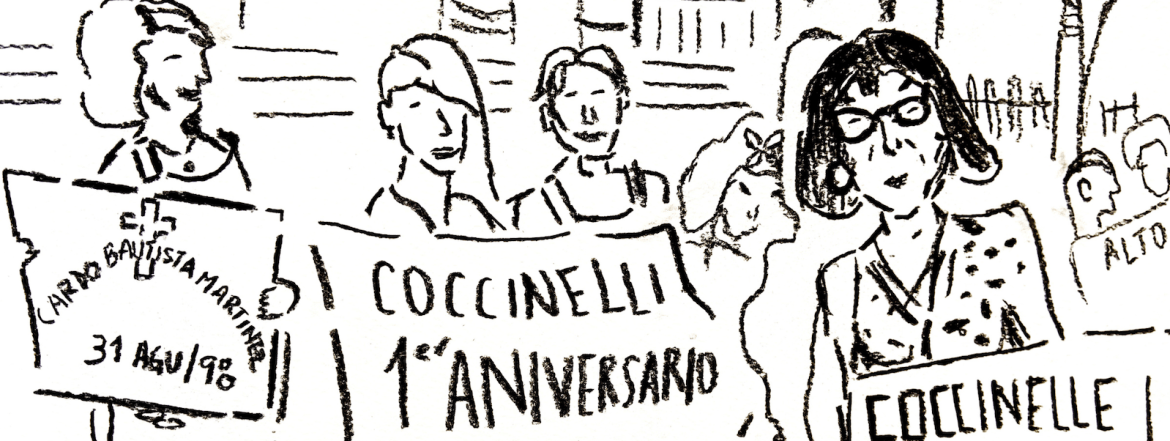

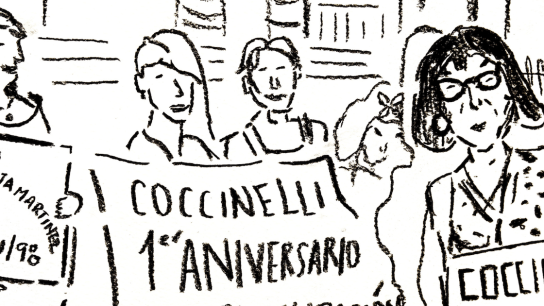

As I walk around the gathering space of La Nueva Coccinelle, a historical trans organization based in the downtown area of Quito, Ecuador, Nebraska Montenegro recounts some of her memories and her compañeras’ in the struggles against the Ecuadorian state in 1997. Until that year, homosexuality was considered a crime in Ecuador, with penalties ranging from four to eight years of imprisonment, as stipulated in the first paragraph of Article 516 of the penal code. Coccinelle played a significant role in the efforts to decriminalize homosexuality, challenging the common use of this law as a tool to control and repress dissident gender identities and expressions, particularly trans sex workers.

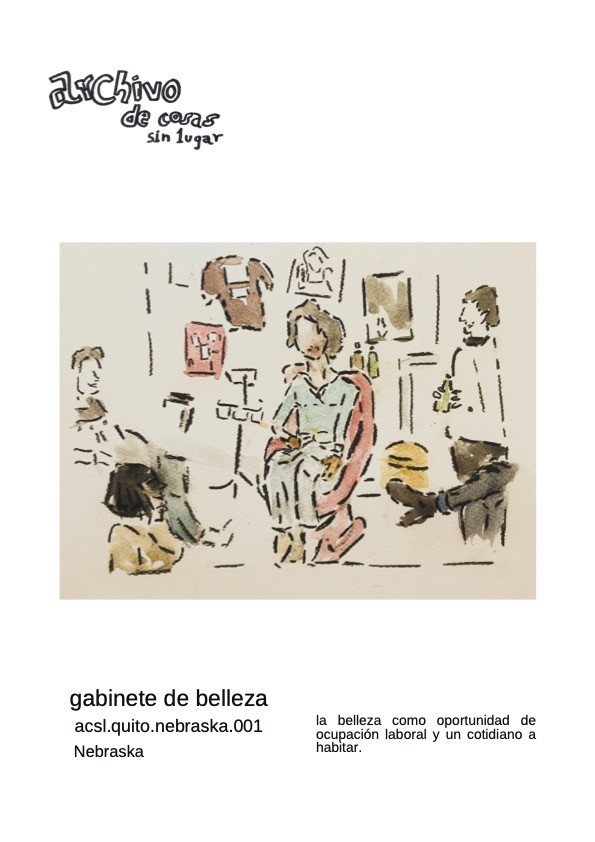

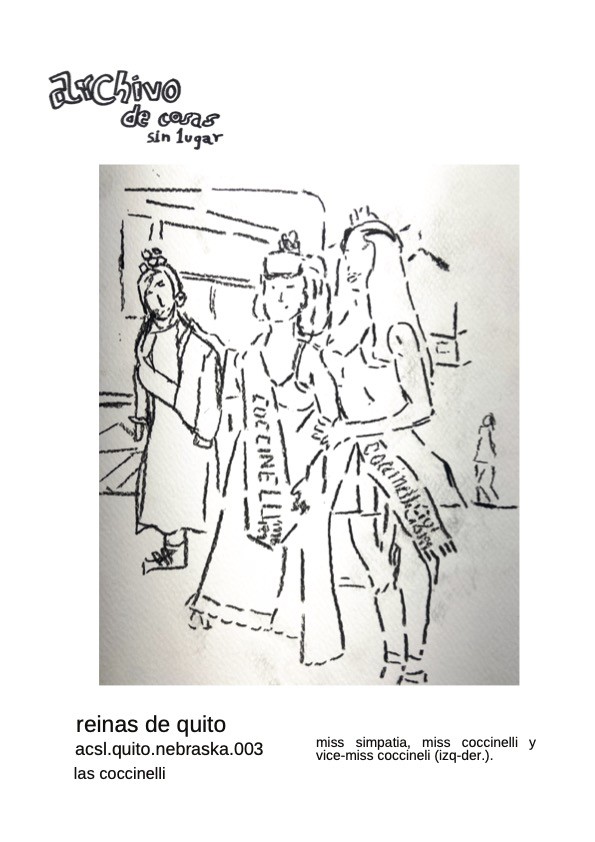

Pointing to some posters adorning the walls, I listen with attention as Nebraska recounts tales of significant public events like rallies and victories in beauty pageants. Yet, she also reminisces about everyday moments like the joy of purchasing her first car, launching a beauty salon after decriminalization, or simply reveling in a party with friends. As a researcher and community archivist myself, I find immense joy and a deep sense of respect in engaging with these memories. However, it wasn’t until I invited Nebraska Montenegro to participate in the installation-performance “archivo de cosas sin lugar” (No Lugar project, September 2023) that I came to better understand the political power of these narratives.1

In her performance, Nebraska shared her memories with local artists and a broader audience. It was not only a chance to engage with history but also to reflect on the present, as the organization and the realities of trans communities in Quito remain little known to many. Indeed, the re-establishment of Coccinelle as La Nueva Coccinelle (‘The New Coccinelle’ in English) in 2019 was a key step toward seeking legal reparation against the Ecuadorian state for crimes against humanity, considering the enduring effects of past violence, contemporary marginalization, and systemic exclusion.

Refusing what some feminist scholars label “progress narratives,” Nebraska’s account brought me a feeling of disorientation and displacement. Like the story of Dana in Octavia Butler’s Kindred, a character who is caught between two times, there is a feeling of continuity that complicates any clearer division between the experienced present and the “overcome” past, as suggested by Denise Ferreira da Silva in Unpayable Debt. In that same frame, La Nueva Coccinelle denounces a significant disparity between the commemorations of the 1997 legal victory, pride celebrations, and other disconnected and institutional allusions to their historical trajectory, and the harsh realities of their current circumstances, which remain neglected.

There’s a fixation on the past that fails to acknowledge those who lived through it and still embody its memories in the present.

This incongruence reflects the adverse conditions faced by many elder members of the community, who deal with various limitations in regard to access to education, employment, healthcare, and social services. In a few words, this disparity underscores the disregard for the contemporary challenges still faced by trans communities. It also confronts an obsession with their past that does not address what is still present from it and affects their current lives. It is as if there’s a fixation on the past that fails to acknowledge those who lived through it and still embody its memories in the present. It’s akin to throwing a party that the celebrated guest can’t attend, or if they do, they’re merely ghosts of their former selves.

Instead of relying on clichés (though they can sometimes be useful) like “remembering the past to avoid repeating it in the future,” what Nebraska and her audience taught me was that an embodied LGBTQIA+ memory is a powerful political action as it queers notions of social progress, democracy, and time. It is not about avoiding something that will happen; it’s about recognizing what is both already and still here. This memory does not fit into a linear history of progress, in which social and political rights necessarily culminate in a better present. Nor is it about creating narratives that stabilize the present, rendering the non-democratic and violent past as something no longer present. It is about acknowledging the limits of a progress narrative and offering a sharp critique of neoliberal narratives of LGBTQIA+ rights and democracy. And from this very material perspective, perhaps we can envision other futures. In a few words, memory work as a grounded activity is premised upon material conditions and concerned both with practical actions and utopian desires. This type of critical position can also challenge the way we understand and organize history, as it is also a strong call to critically reflect on the limits of legal reforms and inquire as to who can access rights and how those same rights are composed.

This resonates with the bold and creative political activism of the Brazilian Black and trans activist Neon Cunha. Neon made history in Brazil in 2014 when she petitioned the Brazilian justice system for a name and sex change without the need of medical or psychiatric reports. At that time, the options for Brazilian trans and travesti individuals to change their documents were either to demand a sex change—based on “biological” or psychiatric evidence, attested by doctors—or opt for the “social name,” a limited and precarious right allowing the use of the name by which the person self-identifies and is socially identified. The “social name” was a sort of a “legal kludge” or “gambiarra legal” in Portuguese, a term coined by the sociologist Berenice Bento.

In light of repeated negative responses from the Brazilian state to recognize her name and gender in non-pathological terms, Neon petitioned the Organization of American States for assisted death in the event of a permanent refusal from the Brazilian justice system. She eventually succeeded, establishing a legal precedent that paved the way for other trans individuals to gain recognition of their identities by the state without being subjected to medical or psychological pathologization.

An embodied LGBTQIA+ memory is a powerful political action as it queers notions of social progress, democracy, and time.

But what I want to particularly reflect on is a powerful historical argument Neon Cunha made during her testimony to the Memorial da Resistência, a museum in São Paulo focused on the history of the Brazilian civil-military dictatorship (1964-1985). As part of a curatorial project produced by Acervo Bajubá, a Brazilian LGBTQIA+ community archive also based in São Paulo, Neon’s testimony contributed to a critical initiative aimed at challenging the limits of the democratic and resistance narratives of the dictatorship. This initiative sought to expand these narratives by incorporating perspectives on gender, sexuality, migration, and identity.

In her testimony, Neon offered a robust critique of the traditional historical approach to defining the duration of the dictatorship and, by extension, of ongoing discussions of LGBTQIA+ issues in Brazilian official history and collective memory:

The [Brazilian] dictatorship didn’t end in 1985; we still feel its remnants today because it didn’t concede defeat. It’s the opposite. Because everyone says, ‘It ended in 1985.’ Ended for whom? Who reformed the military police in 1986? Did that happen? The 1988 Constitution was led by white men who saw themselves as saviors of the nation. And many who survived by making deals during the dictatorship, because it’s not the exiles who will cause trouble. Let’s stop with this nonsense. Because I am a daughter of the dictatorship until the 2000s. I know the dictatorship until the 2000s, which includes the extermination operations, which still carry remnants and practices of the dictatorship […] So, to say that it ended in 1985, for whom? I remained Black, poor, and trans. The dictatorship lingered; even today, we still suffer its consequences. With the current political landscape, can we truly say the dictatorship ended? […] Has democracy truly taken hold?2

Neon Cunha certainly acknowledges the significance of formal political regime shifts in Brazil. However, her central argument delves into the limitations of legal and institutional frameworks, highlighting how they can obscure other realities, experiences, and perspectives on time and history. As an example, this is why she speaks of “survival” rather than “resistance,” a term frequently used in the hegemonic collective memories of that historical period and often adopted by the gay memory of the dictatorship. Similar to Nebraska Montenegro, her critique suggests a flaw in assuming that legal rights or institutional reforms inevitably lead to social change. They both emphasize that critical political action doesn’t always entail outright rejection of the State but can involve contestation and dispute. This is a lesson that could hold particular relevance in the context of the US. As bell hooks once noted, reform alone doesn’t dismantle systems of domination. However, actions such as those mentioned may be crucial to directly addressing systemic oppression and challenging the structures and domains of the State.

Her critique suggests a flaw in assuming that legal rights or institutional reforms inevitably lead to social change.

By invoking her right to refuse living under terms that were not hers, preferring death, she disputed the State’s power not only over name and gender recognition but also its foundational prerogative to govern life itself. The remarkable move she makes is to bring this power into question, exposing its limits and asserting her autonomy in the most profound way. Her concerns are not merely about inclusion, expansion, or change of rights; they are also about disputing the State’s power and authority itself.

Archives and History are not neutral devices. When politically mobilized, they can become valuable tools for social change, as they engage with many of the ideologies that naturalize our status quo—including the notion of subject/being and time. Nation states, in their development, assume a certain type of citizen as the ideal subject and promote a linear narrative of progress, with political transitions and milestones serving to reinforce this trajectory. It is no coincidence that States maintain archives, libraries, and museums to craft and preserve their own historical narrative, often referred to by historians as “official history.” Revolutionaries also grasp this, which is why archives, libraries, and museums are common targets during revolutions.

Dissident memory initiatives are not exempt from this process. Even when guided by notions like plurality or diversity, documenting experiences or assembling archival ephemera can lead to crystallization and stabilization. In other words, the very act of invoking a certain representation can lead to a flattening of experiences. Even disruptive archives run the risk of reproducing these dynamics, as they are far from neutral in their processes of inclusion, exclusion, record preservation, and the construction of the political subjectivity they represent and advocate for. However, this does not diminish their political significance, which extends beyond academic critique to actively challenge dominant structures and open possibilities for new narratives, forms of resistance, and existence itself.

The Argentine Archivo de La Memoria Trans (AMT) in Buenos Aires is an inspiring example of how counter-history and archives can be generative and deployed as powerful tools for radical politics. The archive emerges from a previous virtual space in which Argentine trans women and travestis would share their photographs, letters, chronicles, and testimonies. In 2014, this group led to a formalization of an archive that now holds more than 25,000 documents and engages with exhibitions, political rallies, audiovisual content, and legislative activism. Notably, it was officialized two years after Argentina became the first country in the world to approve a Gender Identity Law that did not pathologize trans identities, serving as a clear reminder that legal reform alone is not enough.

Also committed to an idea of political reparation, AMT’s testimonies and other documents played a vital role in a recent federal judicial decision wherein 10 agents of repression (ministers, policemen, and military agents) were condemned for violence motivated by gender identity during the last dictatorship (1976-1983). These reparations include the provision of a non-contributory monthly pension for transgender individuals who experienced deprivation of liberty following the military dictatorship.

[Disruptive archives] challenge dominant structures and open possibilities for new narratives, forms of resistance, and existence itself.

Through memory work within these “battles of memory,” a term coined by Austrian historian Michael Pollak, the sovereignty over time and history is contested not only against the State but also from within it. History, especially official History, serves as an instance of symbolic production, a site of constant political dispute where narratives are constructed and contested. A place where both present and past are negotiated, reimagined, and instrumentalized to shape collective memory and future possibilities. These ideas can be further understood through a metaphor proposed by the Brazilian trans activist Helena Vieira: “memory as an infiltration.” I really like this metaphor because it effectively points to the power of memory in different national contexts in Latin America. The metaphor allows us to envision different walls with varying degrees of concreteness and porosity. Infiltrations are particularly powerful because they can seep through even the smallest of cracks, gradually eroding the very foundations of the most solid and concrete structures. Even the most resistant materials may not withstand the power of water.

This metaphor also compels us to consider how memory infiltrates and contests the frameworks imposed by the State. Certainly, the incommensurable violence faced by trans and queer subjects must be acknowledged, alongside the essential need to critique the terms set by the State, as Eric Stanley powerfully argues in Atmospheres of Violence. However, it is equally important to recognize the varying porosities of States and their responsiveness to social demands and political claims, which shape distinct opportunities for tactical disobediences and subversions.3 These actions not only challenge the State’s authority but also reveal its fragile and fictive attempts to dictate reality, creating openings to engage with and reconfigure the political terrain. This variability in States’ responsiveness cautions against universalizing the US experience as emblematic of the State and its potential relationships with LGBTQ+ politics, activism, and resistance.

Failing to account for this variability risks assuming that all States function like the US, or that thinking about queer politics and envisioning liberation can proceed without considering these crucial contextual differences. Moreover, it can also close off possible dialogues about practices and imaginaries from the South that can inspire and expand the horizon of possibilities for rethinking resistance against the State and crafting alternative futures, particularly in times when notions of returning to the past fuel conservative and regressive political agendas, shaping not only the present but also the narratives of what is possible.

What if the Queer North goes South?

Although situated in a different historical context and shaped by a different structure of the State, experiences from the South could offer valuable insights for the US context. With these differences in mind, we might ask: What can happen if US queer and LGBTQIA+ politics, academia, and activism cast their glance southward, considering some of the examples I highlighted here? Put plainly: what happens if they go South?

In everyday English, when things go south, it means they take a turn for the worse.4 I choose to play with this ambiguity because discussions of sex and gender politics in the South often grapple with the challenges of translating and displacing theories created in different languages and contexts, particularly those originating in the US. This situation frequently raises questions about the limits of translation and the possibilities for adapting theories across diverse linguistic and cultural landscapes.5 It also prompts inquiries into the conditions and requirements necessary for such adaptations, highlighting the imperialism and colonialism that shape the geopolitics of knowledge.

However, despite these acknowledged limitations and their potential implications, such as the risk of recolonization, imperialism, or the perpetuation of coloniality, numerous generative and critical dialogues have emerged. For instance, in Brazil, with the establishment of LGBTQIA+ rights, queer perspectives assisted Brazilian scholars in inquiring about the limits of representation and citizenship. By considering the different access to social services and rights, scholars like Bruna Irineu and Berenice Bento made insightful uses of theories from the Global North to think of the different possibilities of citizenship in Brazil for sex/gender dissidents. Similarly, one cannot deny that the effects of the US Civil Rights Movement and ongoing diasporic discourses have significantly shaped productive political action within LGBTQIA+ social movements, women’s rights movements, and Black rights movements in the South.

But what if we shift the relation between North and South? That is: what if the Queer North goes South? This does not imply a straightforward translation or adaptation from the South to the US. However, akin to the reappropriations, discussions, and displacements of “queer” in Southern contexts, there is much to be gleaned from the tensions and critical engagements that a queer and racial consideration of LGBTQIA+ memory work, in particular against the State, in the South might provoke.

What kind of “global” are we discussing, and from which perspectives and cosmologies do we define concepts like South and North?

It is a path that promises more productive political insights than the current trend of moving to the South with a predefined agenda, frequently based on concepts alien to that context, such as the much evoked “Global South,” or preconceived notions of gender and sexuality, or the reiteration of the “Other” that solidifies certain models of sex/gender knowledge as if they are not geographically marked as well.6 As Łukasz Szulc observes, subordinated cultures are often treated as ‘particular,’ confined to area specificity in ways that implicitly position American culture as universal (hence not marked). For the author, this dynamic becomes evident in academic settings, such as conferences, where there are often separate panels for “queer” and “global queer,” the latter signaling an othering of non-American contexts. Meanwhile, American culture is implicitly universalized, requiring naming only when it is the explicit focus of study.

What kind of “global” are we discussing, and from which perspectives and cosmologies do we define concepts like South and North? The premise of “global” flows often assumes the privilege of unrestricted academic mobility, enabling some to travel and theorize across contexts even amidst ecological crises—an opportunity that is unequally distributed and often unattainable for many. This mobility shapes who has the power to envision and define the “global,” privileging certain voices while marginalizing others. Rather than reinforcing existing terms, power dynamics, and the division between theory and “ethnographic data,” it is essential to challenge these naturalized frameworks. This is especially crucial when addressing queer and trans politics, where such structures risk perpetuating inequalities under the guise of inclusivity.

In my everyday experiences in the US, I am constantly called upon to give accounts on the state of gender and sexuality experiences in Brazil. From an imperial position, it is always assumed that the US is a safer (and more Modern) place than Brazil. What this simplistic take does not account for is how in both countries, social class, race, gender identity, formal education, and geographic position interfere in the perception of safety and the experiences of violence one may be exposed to for being sex and/or gender dissident. That’s definitely not a new fact for racialized queer communities in the US, including queer and trans migrants. Indeed, there is an already well-established and critical position against the so-called “transgender tipping point.”

Even the most disruptive and critical academic work relies on unequal relations of power.

On a conclusive note, I am not arguing for a romanticized vision of the archival and memory work that is done in the Global South. An easy and disembodied critique can certainly be formulated on how State-focused and inherently exclusive of other experiences these initiatives and their representations may be. From a postcolonial perspective, it is clear that political representations are not neutral, and I am in accordance with the argument that the terms of demands for reparation and inclusion are tied to discursive patterns that can reify some of the “colonial hierarchies of difference now metamorphosed in tropes of citizenship, equality and rights,” as suggested by Mario Rufer. In fact, it is within these tensions and contradictory terms that political actions are conceived and certainly acknowledged by many social activists and the community archivists I have talked about.

Yet one cannot lose sight of how the grounded political action of these collectives and their critical engagements with the State may respond to the urgent material conditions of the present. It is crucial to assess the effectiveness of these actions for individuals and collectives within contexts of extreme violence. I am talking about a present time in which police and State violence toward sex and gender dissidents is still here. I am pointing to a context in which utopia is definitely a goal but the material conditions require an engagement with the contradictory terms of the here and now. As Charles Hale has noted: “[The] utopian image lies on a distant horizon, and the path to get there confronts harsh constraints and immediate needs that must be met with whatever contradictory means we have on hand.”

From the privileged site of academia, the easiest thing to do is to enact a cultural and political critique of such initiatives. They might be theoretically interesting, but what are the material effects of such work? Beyond the cultural critique one can make about these collectives, how can academic work, particularly in the Global North, make use of its privileged position while also being critical of its own contradictory conditions of possibility? What I am saying is that even the most disruptive and critical academic work relies on unequal relations of power.

Many social movements in South America have drawn inspiration from the Civil Rights Movement in the US, despite the historical and political differences between both contexts. My main argument is that there is also value in considering the grounded memory work and critical engagements with the State that have emerged from the Southern hemisphere. I am not suggesting that the conditions for action are identical in the US. As I mentioned, the emergence and conceptualization of queer politics were markedly different in South America, yet these differences have engendered productive tensions in their circulation.

Paraphrasing Charles Hale, utopia is definitely a goal but the material conditions require an engagement with the contradictory terms of the here and now.

In the face of rising political instability, concerns about the fragility of democracy in the United States are increasing. Yet, as Black political thought has long emphasized, true democracy has never been fully realized in the US. A dialogue with memory work in the South contributes to this understanding by offering a critical repertoire for political action. It underscores how the vision of democracy has been shaped by exclusion and systemic inequalities, while also providing tools to imagine and work toward a society that is more just and inclusive. As Cole Rizki asserts about travesti/trans memory work in Argentine:

[The] persistent afterlife of fascism creates conditions of possibility for activists to mobilize the language of anti-fascism and shared memories of fascist violence—namely dictatorship, genocide, and disappearance—in the service of contemporary rights claims. Activists are working against and working with the memory and afterlife of fascism as a shifting ideology and set of material practices that persist into the present [emphasis mine].

By engaging with shared memories of dictatorship, violence, and disappearance, these activists transform the persistence of fascist ideologies into opportunities for contemporary rights claims. This approach calls for intertemporal political action, blending practical initiatives with speculative imaginaries. The embodied queer past, in this context, becomes not only a site of resilience but also a creative refuge for reimagining and striving for transformative political and social change. Especially, and perhaps most powerfully, in the worst of times.

Banner Image Credit: Memoria del futuro (Memory of the Future), charcoal drawing based on a photo from the Nueva Coccinelle archive. This image, along with the other two, was created by the author as part of the installation archivo de cosas sin lugar, presented during the open studio of the residency program at No Lugar gallery, Quito, Ecuador, in September 2023. The author expresses their gratitude to Gledys Anael Macías (Museo de la Memoria, Ecuador) and Nebraska Montenegro for facilitating access to the digitized versions of the originals.

This publication was supported in part by the University of California Office of the President MRPI funding M22PS5863. UCHRI thanks editor and writer Michelle Chihara for her developmental work with the series contributors.

Notes

- I am grateful to the UCHRI Work and Refuge grant for funding my stay and research in Quito, Ecuador. Visit my Instagram for pictures and more information on “archivo de cosas sin lugar.”

- Translation by Yuri Fraccaroli.

- Referring to Michel de Certeau’s distinction between strategy and tactic, tactics involve the transformation of ‘events’ into ‘occasions,’ while strategy entails calculations from the domain of an isolable place within an environment. This place can be circumscribed as a self, thereby serving as a basis for managing its relations with a distinct exteriority.

- I encountered this expression in the syllabus of ‘Becoming-South: Latin American and Latine Performance Studies,’ prepared by Prof. Leo Cabranes-Grant (Department of Theater and Dance, UC Santa Barbara) for Winter 2024. I am grateful to Prof. Cabranes-Grant for providing this insightful material.

- Here I am thinking of the important work of Queer/Cuir Américas and scholars: writers and thinkers like Cole Rizki, Joseph M. Pierce, Patricio Simonetto, Suzy Shock, Marlene Wayar, and Hija de Perra, among others.

- I am inspired by the reflections Robert McKee Irwin proposes around Roger N. Lancaster’s “caveats.” In particular, I point to the (implied) risks of overgeneralization/overspecification and the quote: “Binary models of difference ignore not only historical cultural interchange but also the diversity of beliefs, practices, and identities within the arbitrary boundaries of national culture.”