Tracing Everyday Upheavals in the Middle East: An Interview with Ingy Higazy and Raed Rafei

by

Ingy Higazy and Raed Rafei (UC Santa Cruz) spoke to UCHRI Research Grants Manager, Sara Černe, about pandemic collaboration and podcast experimentation for a Foundry series highlighting the work of the Institute’s recent grantees and the methods, unorthodox approaches, and challenges they have employed and encountered.

“How can we shift the gaze to the mundane and creative ways upheaval is being lived and experienced in the Middle East? […] We approached upheaval as we would approach an artwork: each month, we produced a collection of writings and entries that straddled both creative and academic inputs.”

Tell us about your project and some of the most surprising everyday affects and hidden forms of resistance you’ve encountered in your research.

“Tracing Everyday Upheavals in the Middle East” is a multi-campus project that departs from grand totalizing narratives of upheaval by unearthing intimate histories, complex presents, and imagined futures from across the Middle East. Our main research question is: What are the different stories and narratives of upheaval that we can derive from everyday life?

We are a group of nine historians, political scientists, sociologists, anthropologists, and film and media scholars from four UC campuses that share a personal and academic engagement with the Middle East: Raed El Rafei, Ingy Higazy, Aida Mukharesh, and Lalu Esra Ozban from UC Santa Cruz; Salma Shash, Gehad Abaza, and Mary Michael from UC Santa Barbara; Yasemin Taskin-Alp from UC San Diego; and Banan Abdelrahman from UC Berkeley.

Our goal was to think together about genres and sub-cultures that are far from the mainstream, yet are embedded in structures of oppression in the Middle East. We were thrilled to make connections between mundane forms of political activism and fringe artistic movements, particularly in the aftermath of the Arab Spring a decade ago. For example, we thought about queer activism and queer artistic works in the region, particularly in Lebanon and Turkey. We connected this line of inquiry to histories and representations of other disenfranchised groups, such as revolutionary youth in Lebanon, skilled migrant laborers in the Gulf, and sex workers in colonial Egypt.

Some of the most surprising forms of resistance (to authoritarianism, patriarchy, nationalist hegemony, religious fundamentalism, etc.) we encountered in our research included hip hop music and translation. We were, for instance, impressed by the power of stand-up comedians’ incendiary social media videos commenting on government corruption. We found that these forms of daily dissidence were gradually helping to dismantle dysfunctional political systems as well as patriarchal ideologies at their root.

For one long and fruitful year, our group thought about, analyzed, and discussed different artistic genres from the Middle East. We were keen not to think of the Middle East as exclusively a region of upheaval and unrest. This directed our focus to non-mainstream art forms—from queer cinema to hip hop and rap music—that are currently flourishing in the region.

In the countries we study, formal spaces for public and political life shrink by the day. Formal political processes, like elections and polls, are usurped by state and geopolitical forces. There also exist long histories of state control of art and mainstream artists. This political context made our critical approach to alternative modes of political expression and activism (social media being the most prominent one among them) both urgent and necessary. Thinking about art in the Middle East cannot be separate from thinking politically about expression, public life, political accountability, narration, representation, and much more.

Methodologically, we centered non-state and non-tangible archives in our collective thinking and writing. We approached upheaval as we would approach an artwork: each month, we produced a collection of writings and entries that straddled both creative and academic inputs. For the past decade, various artistic media were central to our attempts to grapple with upheaval in the region and globally. Capturing upheaval through artwork—both by others and our own—felt natural and yet new and challenging. How can we communicate the importance of those immaterial archives to a broader public, some not familiar with the region? How can we shift the gaze to the mundane and creative ways upheaval is being lived and experienced in the Middle East? This led us to center upheaval as both our method—upending and decentering dominant methodologies—and our object of thinking and reflection.

“It was truly valuable to have the space and time to build community and think collectively—what we believe is the essence of academia—amidst individual and global uncertainty.”

What were some of the public-facing outcomes you created and the technological and translational challenges you encountered when trying to speak to a broader audience?

We shared some of our reflections on upheaval in the form of an online interactive map. In addition to personal diary entries, commentaries, observations, and resources, we recorded a podcast toward the end of our project to collectively discuss our thoughts around the layered meanings of upheaval.This exercise helped us shape and refine our thoughts with a broader public in mind. We began by reflecting on some of the challenges we faced in our working group. How can we contribute to ongoing conversations in academia and in the region around upheaval? How can we engage our interlocutors, inside and outside the academy, interested in untangling the many effects of upheaval on our personal and political lives?

“[Podcasting] was the least technologically-demanding, yet most rewarding of our interactive endeavors. We will definitely incorporate it in our future research and we would advise other graduate students to experiment with the medium, too!”

As scholars across the humanities and social sciences, we were aware that podcasting is becoming an increasingly important medium for creatively disseminating our research findings to the broader academic community and beyond. With this in mind, we wanted to creatively explore it (and have fun doing so!). In addition, widely sharing our findings, especially with the communities whose art and writing we thought with and drew on in our year-long working group, was a priority for us. We relied on our phones as recording devices and on online editing tools to produce our podcast. And it was the least technologically-demanding, yet most rewarding of our interactive endeavors. We will definitely incorporate it in our future research and we would advise other graduate students to experiment with the medium, too!

Have the working group and the funding you received transformed your individual research or the way you approach academia?

The UCHRI Multicampus Graduate Student Working Group funding made our meetings and collective thinking possible at a turbulent time in the world. The COVID-19 pandemic interrupted many of our individual field research plans while we were all at a critical stage in our academic careers. It was truly valuable to have the space and time to build community and think collectively—what we believe is the essence of academia—amidst individual and global uncertainty. Because of the grant, we had the support and opportunity to live and think through the upheaval of the pandemic together.

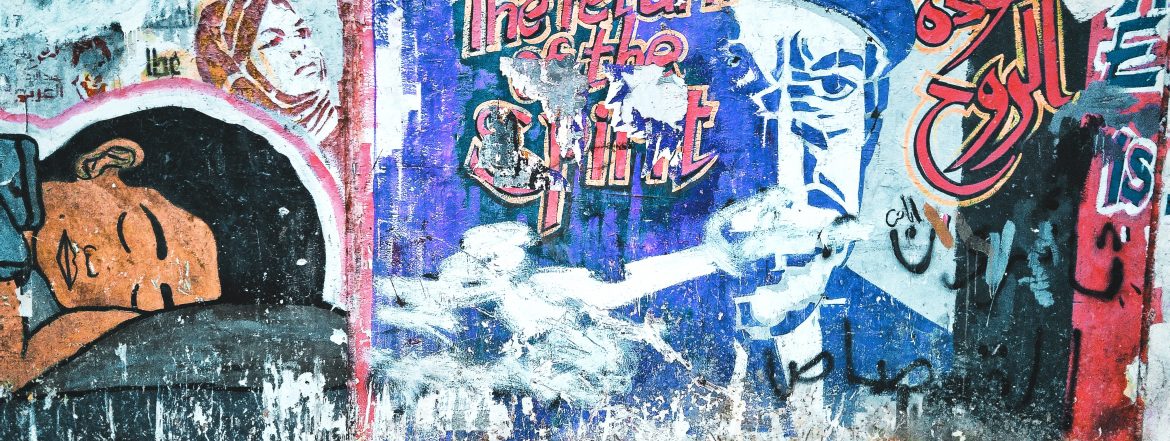

Banner image credit: Baher Khairy