Recuperating History through Community-Engaged Research in the Pajaro Valley

by

In the early hours of January 23, 1930, eight white men fired bullets into the John Murphy Ranch on San Juan Road in California’s Pajaro Valley. A single bullet from the violent assault punctured the heart of Fermin Tobera, a 22-year-old Filipino farmworker who was killed instantly as he slept in his bunk during the attack.

Known to house migrant Filipino agricultural workers, the ranch was among several establishments targeted by white rioters who, over the previous four days, had battered and harassed the valley’s Filipino residents and workers, especially those in and around the city of Watsonville. Incendiary anti-Filipino remarks by a public official, xenophobic fears of miscegenation and interracial intimacy, and wide unemployment ushered in by the Great Depression incited the mob violence that marked January 1930. Tobera’s murder, one local periodical reported, “ended” the days of terror.

Recuperating History

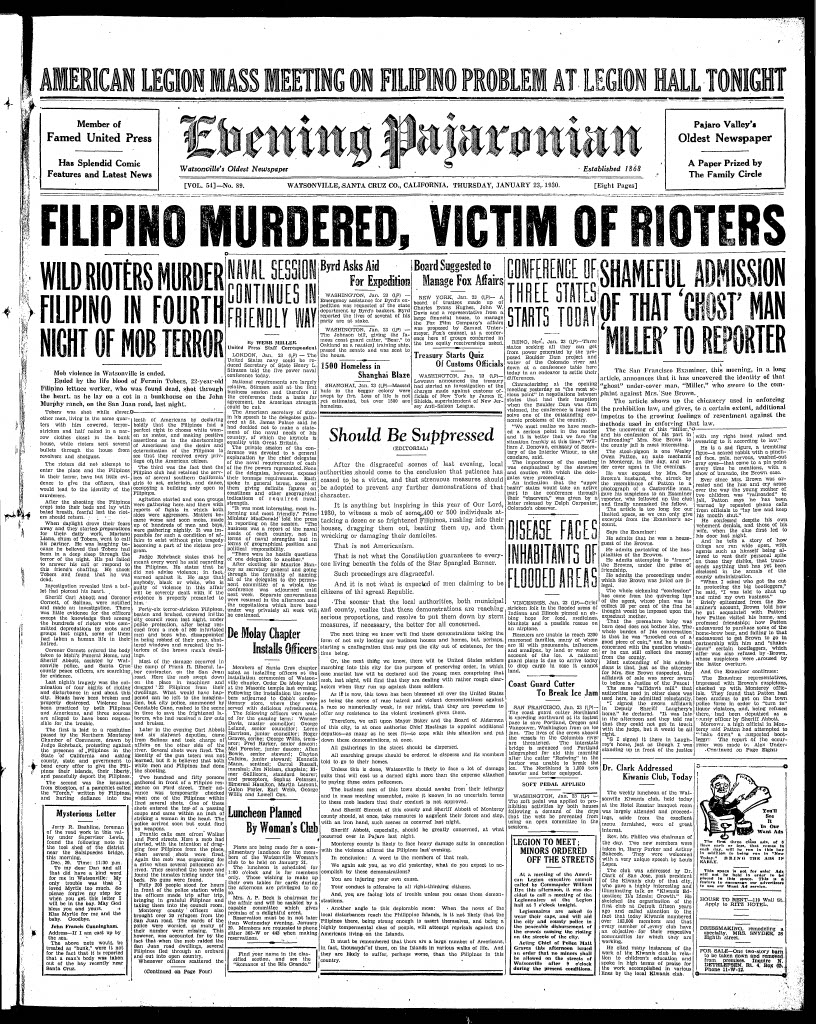

For over 90 years, nearly all we knew of what would become known as the “1930 anti-Filipino Watsonville race riots” came from a handful of journalistic accounts. Local newspapers such as the Evening Pajaronian offered the only glimpse into the events that transpired that January. References to Filipinos and their “unsanitary living habits,” terms like “goo-goo lovers,” and descriptions of “machine-loads of American youths” who participated in violent altercations paint the image of “race hatred” that overtook the Pajaro Valley. Largely faceless and unnamed, Filipinos emerge in these sources as adversaries and cowering subjects. Only on the rare occasion are they described as vocally opposed to the discrimination of the time.

Upon the ninetieth anniversary of the race riots, The Tobera Project, a Watsonville-based grassroots organization composed of the descendants of the first Filipino farmworkers to settle in the Pajaro Valley, partnered with faculty and students at UC Santa Cruz to form Watsonville is in the Heart (WIITH). A community-engaged research initiative, WIITH—of which the authors are a part—seeks to document, preserve, and uplift the histories of Filipino labor and migration in the Pajaro Valley. Since 2020, we have worked with The Tobera Project to conduct oral history interviews, digitally archive precious family materials, curate physical and web-based exhibitions, and design high school and college-level curricular material that focuses on a significant yet heretofore shallowly understood Asian American enclave.

While foundational to Filipino American and Asian American history writ large, the riots unfortunately cast a long shadow over other understandings of Filipino lifeways in the valley—a shadow crudely built upon sensational coverage and limited accounts of how Filipinos themselves experienced life on California’s Central Coast in the 1920s and 1930s. Among our goals, therefore, is to recuperate and share widely a more detailed history of the race riots and Filipino community formation, one hinged on the power of community-based research and the opportunities presented by public history.1

Community-Engaged Digital Mapping

In 2023, WIITH partnered with scholars at UC Berkeley to document and digitally map the violent exclusion of Filipinos and their concurrent community-building in the Pajaro Valley. We aimed to interrogate how and where Filipino migrants and their families created spaces of belonging in the face of civic ostracism and racialized non-citizenship in the Pajaro Valley.2 Against a backdrop of historical erasure of Filipino presence in the area, we chose to pursue digital mapping for the purpose of visualizing what refuge and its refusals could have looked like in 1930 and over the twentieth century.3 With digital maps, we also aimed to fulfill our community partners’ requests for interactive, accessible, portable resources to teach students and members of the public about the 1930 anti-Filipino Watsonville race riots and local Filipino American history.4

WIITH created two multimedia maps that highlight archival primary sources, including newspaper articles, photographs, documentary footage, and excerpts from our cache of oral history interviews. The maps also include contemporary photographs and “re-photographs” of archival images taken by our team that document important locations.5 These images and re-photographic comparisons mark the environmental and infrastructural changes that have occurred in the valley from the 1930s to the present, and allow map users to situate these histories in their contemporary environment.

The first map chronologically traces the events of the riots and their transpacific reverberations as news of the violent attacks and Tobera’s murder traveled throughout the Filipino diaspora in California and Hawai‘i and to the Philippines, prompting critiques of US racism and empire. To build the map, our team drew on journalistic and oral accounts of the violence that occurred in the Pajaro Valley between January 19 and January 23, 1930 and the movement of Tobera’s body from Watsonville to his hometown of Sinait, Ilocos Sur, where he arrived on March 17, 1930.6

The second map, which we refer to as a “counter-map,” marks sites of belonging for the Pajaro Valley Filipino American community. This map showcases spaces where Filipino migrants and their families found refuge despite racist acts, exclusionary laws, and their status as non-citizen US nationals. The counter-map centers WIITH oral history interviews and archival photographs to locate places that are remembered as important to the Filipino community, categorized into five themes: sites of gathering, Filipino-owned businesses, social organizations, interracial relations, and labor. When the first and second maps are compared, sites of racial violence overlap with those of belonging.

To build the maps, our team conducted fieldwork with second-generation Filipino Americans, who joined us for archival visits, geolocative mapping, photography, and re-photography in the Pajaro Valley. Seven paid community researchers led us to locations where anti-Filipino violence occurred and places where they lived and communally gathered. In the field, we used archival photographs, often originating from our community researchers’ own family collections, to elicit historical and geographic information.7 Community researchers’ knowledge of local landscapes and histories allowed us to locate sites found in archival images and textual and oral accounts as well as others not mentioned in previously collected material. They shared their own and their families’ place-based memories.

“The re-photography method spurred community researchers’ recollections, which often expanded upon information they provided during formal oral history interviews conducted with our team.”

Community researchers also assisted in our re-photography, or the re-taking of an older photo in the contemporary moment to document social and physical change over time and to elicit comparison and/or juxtaposition.8 While in the field, the re-photography method spurred community researchers’ recollections, which often expanded upon information they provided during formal oral history interviews conducted with our team. The stories told during fieldwork were recorded and are featured as audio snippets embedded within both digital maps alongside archival photos, re-photographs, and oral history excerpts.

Aligning with WIITH’s commitment to critical community-engaged research methods, we positioned community members as expert researchers.9 We found that what they knew widened and, at times, contradicted narratives told in archival sources. In the following section, we reflect on three instances of incongruence that we encountered while creating our digital maps.

Incongruence and Corroboration

Watsonville’s Palm Beach Dance Hall, owned by the Irish American Locke-Paddon family, was the flashpoint for the violence of January 1930. Filipinos rented a space within a Locke-Paddon property to hold dances. Most of the historiography surrounding the race riots includes this location as a salient representative of the event in general. Pinpointing the location of the dance hall, however, was not as simple as we anticipated. When our team attempted to find the physical location of the establishment, we discovered that some photos of what was thought to be the hall had likely been doctored for postcards. With community insight, we located the building from the archival photographs; it was situated proximal to a former pier north of Beach Road. We were confident in this location until we conducted an oral history interview with one of the owner’s sons, Kenneth Locke-Paddon.

In his interview, Kenneth described his own memories of the location, revealing that there had been Filipinos and white migrant families from the Southwest—among others—lodging around the dance hall, making Palm Beach its own small community by the water. Upon his review of our archival findings and photographs of the dance hall’s location, he informed us that the printed materials were mistaken. The dance hall had been a multi-purpose ballroom within a hotel that his father owned. Kenneth subsequently identified the building in the archival photographs as a casino that had burned down before 1930. Following the oral history interview, he and his wife showed us maps of the area and pointed out buildings on the Locke-Paddon property, just south of Beach Road. Instead of the barren area previously thought to be the location of the Palm Beach Dance Hall, the hotel and housing that made up the Palm Beach community were in the center of what is now a gated neighborhood of vacation homes. Our team returned to photograph the area, which we now believe to be closer to the actual location of the Palm Beach Dance Hall.

Our team encountered similar challenges navigating the incongruence in memories of violence that occurred near the Pajaro River bridge. Likely the next most popular story told about the 1930 riots, both within the community and in historical works, is of rioters pushing Filipinos off of a bridge into the Pajaro River. As we examined newspaper sources, we found only one article that could be the source for this story. It included a single sentence, reporting that “several Filipinos were driven across the bridge into Pajaro.”10 Although it is possible to interpret this as if several Filipinos were thrown into the river, the township across the river from Watsonville has also changed names multiple times, and in consulting maps from 1930, we discovered it was known by the same name it holds now: Pajaro. It was uncomfortable to dispute a common refrain within the community and among scholars, but we simply did not have enough evidence to conclude that Filipinos were thrown off of the bridge. They were more likely forced across the bridge and out of Watsonville. These issues in the historical narrative speak far more to the multiple layers of historical erasure at play than to any shortcomings in community and archival knowledge; community members made educated inferences based on the evidence available to them.

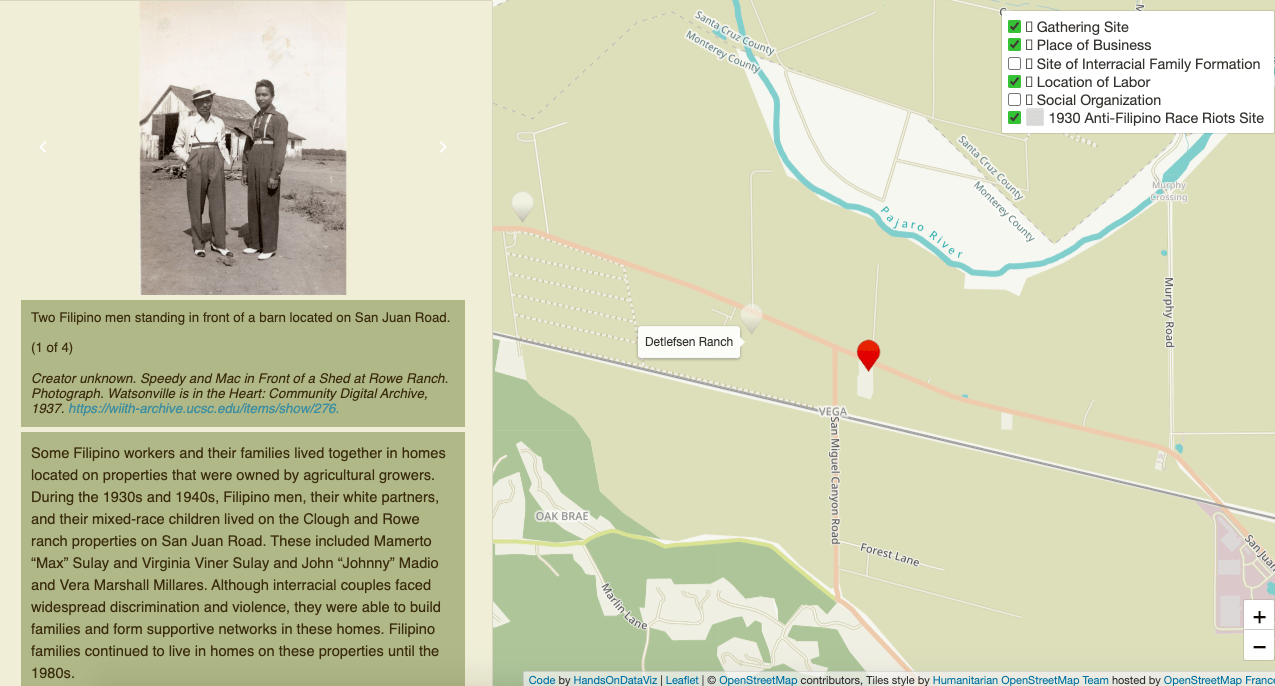

Between January 19 and 23, 1930, groups of white rioters attacked communal labor camps or bunkhouses where Filipinos were known to live. According to reports published in the Evening Pajaronian, a mob raided Filipino residents at Detlefsen Ranch during the late hours of the night on January 22.11 Writing for local audiences, the paper did not provide exact locations for the camps or the ranch. While addresses for laborers’ residencies were often not recorded in city directories, our team consulted maps held at the Pajaro Valley Historical Association (PVHA) and other local repositories to locate the ranch.

During our research, we encountered two challenges: first, many of the ranches where Filipinos lived and worked in 1930, including the property owned by the Detlefsen family, were located on a rural stretch of San Juan Road that straddles Santa Cruz and Monterey counties. Few of the maps we accessed recorded this peripheral region. Second, the PVHA and other repositories do not have maps dated to the 1930s that include Detlefsen Ranch. As such, we had to rely on maps created during the 1940s and 1950s to roughly ascertain what the property lines for Detlefsen Ranch would have been in 1930.

To corroborate the location, we enlisted the help of Antoinette DeOcampo-Lechtenberg, a descendant of a Filipino farm worker who grew up and was a longtime resident of the rural region of the Pajaro Valley. Prior to our fieldwork, we shared the names of multiple ranches mentioned by the Evening Pajaronian. Antoinette guided our team to what she suspected to be the site of Detlefsen Ranch, located immediately adjacent to the Rosser-Lazo-DeOcampo Ranch, property that was purchased by her aunt, May Rosser. Although Antoinette did not have written records, stories passed through her family and her familiarity with the land made her confident in the location of Detlefsen Ranch. We subsequently finalized the geolocation marker for the map based on her knowledge.

For Antoinette, our day in the fields brought forth memories of how her own family circumvented exclusionary laws targeting Filipinos and instead made lives in the Pajaro Valley. Remembering an uncle’s home located behind her family’s ranch, Antoinette shared:

So this is my uncle’s house and in the backyard he’d have all his fishing gear. And you’d walk in and it’d smell very typically like a Filipino’s house—fish, cigars, and dirt—you know, it’s like you live in the dirt. . . . But my uncle’s house back there was a three-bedroom house and that’s where all the barbecues, all the raising of the goats, the pigs, the slaughters. . . He was very important because he was the hub. I mean the big—the real Filipino parties happened over here.

In conversations with Antoinette and other descendants, we heard stories of many other Filipinos and mixed-race families who lived and worked in the area around San Juan Road in close proximity to Detlefsen Ranch. One such place was a farmhouse that had been converted into a communal bunkhouse for workers known to many as the “Rowe Ranch House.” The WIITH digital archive includes sixteen photographs depicting Filipino workers and their families living at what is thought to be Rowe Ranch. These photographs were contributed by Juanita Sulay Wilson, a mixed-race Pajaro Valley Filipina who lived in the camp with her parents, relatives, and family friends during the 1940s.

As in the case of Detlefsen, we were unable to locate the 1930 property lines and addresses for Rowe Ranch using sources in local repositories. Again, we turned to community-based memories to acquire geolocative data. During our fieldwork with Antoinette, she led us to a Victorian-style farmhouse and barn on the corner of San Juan and San Miguel Canyon roads, across from the sites of Detlefsen and her own family’s ranches. Based on personal memories and those elicited by archival photographs, she suspected the house to be Rowe Ranch. To investigate further, our team was able to gain access to the property and building, which, at the time, was under construction. We returned with Antoinette, Juanita, and copies of the archival photographs in the hopes of confirming the location as the Rowe Ranch house. Using the landscape and architecture pictured in the images, we attempted to find similarities.

“With our pursuit of community-engaged research, we have a more developed snapshot of the time period, the ripple effects of the riots themselves, and the community formation that happened in spite of such a painful marker in history.”

While our team felt it was likely that the location pictured in archival photographs matched the house, we became uncertain if it was indeed owned by the Rowe family. Further discussions with local community members, however, revealed alternative names for the house on the corner of San Juan and San Miguel Canyon roads and suggested another farmhouse known as the Rowe House had existed several miles to the south. Although the identity and original owner of the buildings pictured in Juanita’s photographs remains ambiguous, community-based memories indicate that the house and other labor camps and residences that stood in the surrounding area were important sites of belonging for interracial couples and mixed-race families who lived and worked in the rural Pajaro Valley. Due to the significance of the site in the community’s collective memory, we decided to include it on the counter-map alongside markers for the ranch and homes that belonged to the Rosser, Lazo, and DeOcampo families.

First impressions of Watsonville’s Main Street in the downtown area reveal no clues as to an “urban renewal” project of the 1980s sanctioned by the city that took away a host of Filipino and other minority-owned businesses and places of leisure. There are no markers to remember community institutions like Philippine Gardens or Daylite Market; no indications as to the bustle that used to prevail in this part of town also known as “Lower Main,” historically frequented by communities of color. In the early stages of our project, it was difficult for our team to locate the sites of businesses that were relevant to the Filipino community because street widening confused the system of addresses.

“Through [participants’] memory and resources shared by other community members, we were able to finally see the 200 block as the thriving site of belonging it was before redevelopment.”

Dana Sales, the son of a Watsonville Filipino migrant, was our guide to the 200 block neighborhood. His father Florendo Macadangdang Sales was a barber in Watsonville’s downtown from the late 1940s until redevelopment forced him out of the shopfront he bought on Main Street. Dana recalled a time when his father told him, as he looked out of his shop window, that his business was finally safe now that he was on Main Street, in plain view of the city hall. Florendo only found out that his store was to be demolished when reading the newspaper. As a member of the city planning commission when the push for “urban renewal” began, Dana became deeply involved in the fight to preserve Watsonville’s downtown community. Through his memory and resources shared by other community members, we were able to finally see the 200 block as the thriving site of belonging it was before redevelopment.

Strengths of Community-Based Knowledge

The 1930 race riots have been a touchpoint for many scholars of Filipino America. Our research has not necessarily produced a new timeline of events or uncovered other reasons behind the senseless violence that shook the Pajaro Valley. Yet, with our pursuit of community-engaged research, we have a more developed snapshot of the time period, the ripple effects of the riots themselves, and the community formation that happened in spite of such a painful marker in history. We consider these as manifesting in both our research product and research process.

“With [our community partners], we saw the Pajaro Valley through different angles of vision not afforded by typical archival material. For them, remembering community formation was just as, if not more, meaningful than mapping the riots.”

The outcome of our project has worked to make history of Pajaro Valley Filipino Americans more accessible. The digital format of the maps meets the expectations of our community partners and local educators, who can more readily visualize and ascertain histories of racial exclusion and belonging at home, in the classroom, and out in the field. We contribute to existing written and creative renderings of the riots, offering a more visualized version of refusal.12 This spatial approach gives local community members in particular the chance to envision changes over almost a century of different erasures, some under the guise of urban renewal. Our contemporary photographs and re-photographs alongside archival materials and moving images activate the historical textures of places since replaced by gas stations, fast food establishments, and parking lots.

In terms of process, our community partners drove our project. The re-photographs we took were elicited from archival work and community engagement: Our partners brought us to the sites that mattered to them and that resonated with the archival material we were able to unearth. They clarified to us the necessity of the counter-map. With them, we saw the Pajaro Valley through different angles of vision not afforded by typical archival material. For them, remembering community formation was just as, if not more, meaningful than mapping the riots. With their collaboration, we were also able to more accurately identify points on our map of the riots and not just those reiterated by other scholars. Indeed, the community-engaged element of our work made the spatial approach possible, helping us recognize how Filipino communities stayed if not thrived in places where extreme exclusion had occurred just years or decades prior, revealing the imbricated layers of historical refuge and its refusals.

Banner Image Credit: Pajaro Valley Historical Association

Notes

- Margo Shea, “Participatory Methods and Community-Engaged Practices for Collecting, Presenting, and Representing Cultural Memory,” in Danielle Drozdzewski and Carolyn Birdsall, eds. Doing Memory Research: New Methods and Approaches (Singapore: Palgrave Macmilian, 2019); Michelle Fine and María Elena Torre, Critical Participatory Action Research (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2021).

- Claire Jean Kim, “The Racial Triangulation of Asian Americans,” Politics & Society 27, no. 1 (1999): 105-138.

- Our project was developed in response to UCHRI’s initiative to examine “Refuge and Its Refusals” in 2023. Following scholars of critical refugee students, we define “refugee” as a complex subject shaped by forces of displacement, colonialism, and who is only partially accepted in their new land of relocation. Early twentieth century Filipino migrants, classified as “US nationals,” occupy a similar liminal position as the refugee as they were only extended partial legal rights in the US. See Yen Lê Espiritu, “Toward a Critical Refugee Study: The Vietnamese Refugee Subject in US Scholarship,” Journal of Vietnamese Studies 1, no. 1-2 (2006): 410-33.

- One of the major hurdles in this project was bridging the gap between our imagined outcomes for the maps and what was actually possible to create using readily available digital mapping platforms. We settled on Leaflet, an open-source project that provides the necessities for digital mapping and offers much in the way of customization. We used templates provided by Hands-On Data Visualization that served as a springboard for designing our maps. We code-customized these templates for audience accessibility. The physical mapping process consisted of plotting points gathered during fieldwork outings in a preliminary space utilizing Google MyMaps. We were able to mark the majority of map locations before moving into the Leaflet template to tell a more cohesive story. As points and their respective media were added, the design of the maps began to come together as visual aids and teaching tools.

- On re-photography, see I.R. Berson and M.J. Berson, “A slippage of time: Using rephotography to promote community-based historical inquiry,” Social Education 80, no. 2: 113-117. See also Bretton A. Varga, “Posthuman figurations and hauntological graspings of historical consciousness/thinking through (re)photography,” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 37, no. 3 (2022): 785-815.

- To create the first map, our team conducted archival research that consisted of re-evaluating extant journalistic sources and incorporating new material. We expanded our view of the historical landscape by including Filipino and Filipino American publications held at the Bancroft and University of Washington libraries that have been previously unused in most scholarly treatments of the riots. These included stateside publications such as The Three Stars and The Philippines Herald which was published in Manila. Our undergraduates conducted close readings of the Evening Pajaronian, completed research trips to the Pajaro Valley Historical Association (PVHA) archive, and analyzed approximately seven hours of rare documentary footage held at the National Pinoy Archives (NPA) in Seattle. At the PVHA, students made use of maps, town registries, and photographs to find sites of violence.

- Douglass Harper, “Talking about Pictures: A Case for Photo Elicitation,” Visual Studies 17, no. 1 (2002): 13-26; Joshua Bell, “Losing the Forest but not the Stories in the Trees: Contemporary Understandings of F. E. Williams’s 1922 Photographs of the Purari Delta,” Journal of Pacific History 41, no. 2 (2006): 191-206; Analyn Salvador-Amores, “Afterlives of Dean C. Worcester’s Colonial Photographs: Visualizing Igorot Material Culture, from Archives to Anthropological Fieldwork in Northern Luzon,” Visual Anthropology 29 (2016): 54-80.

- Vergara Camilo José, American Ruins, New York: The Monacelli Press, 1999.

- Steve McKay, “Critical Engagement: Deepening Partnerships for Justice,”Footnotes: A Magazine of the American Sociological Association 50, no. 1 (2022), accessed September 3, 2024.

- Evening Pajaronian, January 20, 1930.

- Evening Pajaronian, January 27, 1930 and February 24, 1930.

- Rick Baldoz, The Third Asiatic Invasion: Empire and Migration in Filipino America, 1898-1946 (New York: New York University Press, 2012); Howard De Witt, The Watsonville Anti-Filipino Riot of 1930 : A Case Study of the Great Depression and Ethnic Conflict in California (Los Angeles: Historical Society of Southern California, 1979); No Dogs, directed by Randal Kamradt, 2021, film; Conrad Panganiban, Standing Above Pajaro, 2024, play; Randy Ribay, Everything We Never Had (New York: Kokila, 2024); Karen Yamashita, Dark Soil: Fiction and Mythographies, ed. Angie Sinjun Lou (Minneapolis: Coffee House Press, 2024).