The Political Lives of Kelp & dAXunhyuu

by

“Holding Sway: Seaweeds and the Politics of Form” is a series of photo essays that channels a visual curiosity about seaweeds with considerations of militarization, gender, Indigenous sovereignty, extractive regimes, and climate change. Foundry guest editors Melody Jue and Maya Weeks invited participants to create or curate images that literally and figuratively “hold sway” in two senses: capturing the attention of an audience, or conveying a relationship of being in touch with seaweeds by holding their swaying botanical forms.

“Kelp is a rising star, a golden child of climate change who is said to have the potential to fix the knottiest branches of climate change issues that it did not help create. This sounds like a lot of pressure to put on one organism. We know the feeling.”

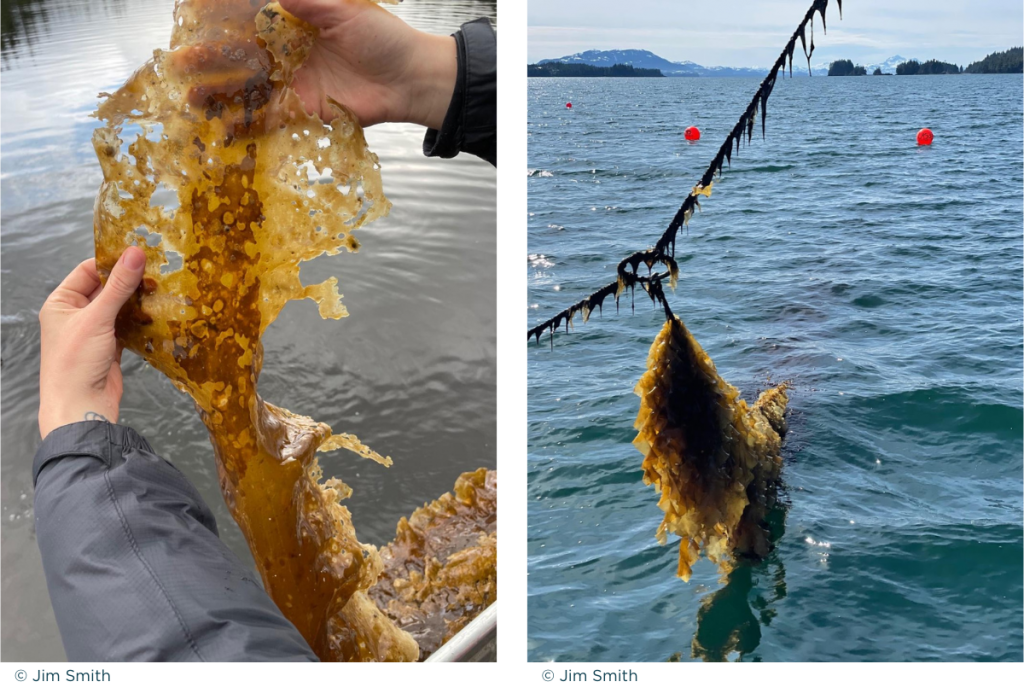

Kelp babies are fragile. To plant them, a careful process of gradual temperature exposure to cold ocean water must be followed to ensure their survival. For the last several years, Jim has been planting kelp babies in their beds and watching their growth through the seasons in our homewaters near dAXunhyuu territory.

Kelp is a beautiful creature, providing shelter and habitat, a foundation for a whole ecosystem. It is also a food stuff and can be rendered into any number of materials useful for modern human life. Kelp is a rising star, a golden child of climate change who is said to have the potential to fix the knottiest branches of climate change issues that it did not help create. This sounds like a lot of pressure to put on one organism. We know the feeling.

Just as kelp is enlisted to fix carbon problems, Native peoples, too, are hailed to answer a call for a climate-apocalypse future they did not help enact. Our ongoing and historical political systems of government, trade, and international sovereign relationships are downplayed to instead highlight our expertise about the environment—the white savior archetype is, in this moment of climate change, no match for Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK).

Yet for the devouring eyes and minds that look to us and upon us, we must narrate out a consistent story of demise and decline, resilience and revitalization—in that exact order—that operates within a settler orientation to linear time and crisis. Only then can we be deemed appropriate stewards for a planet shaped by colonial-capitalism.

To be dAXunhyuu growing up and living in one’s homelands is not a shield from the narratives of disappearance and death of Indigenous peoples that America feeds itself. This myth of disappearance is consistently maintained in American consciousness, a story birthed with the country itself, yet somehow it seems to never get old. Marketed alongside the story of disappearance is that of resilience—it presents itself as a new story, but it is actually the same narrative in cosplay.

It follows that in a world working to change itself in one part through justice and in another part through alternative, diverse forms of story, the replacement of the death narrative would be one of reclamation and revival. If all that is known of Indigenous peoples is their disappearance and destruction, the clear alternative story of progress must be their fight to not be disappeared.

We’re tired of both narratives. Resilience requires violence in an original form, and again and again in its telling and retelling. One can only be resilient if they continually experience harm.

One might sort the political history of Eyak people into discrete moments of disappearance and salvation. Punctuated moments of spectacle.1 The reality is a steady hum of life and living.

“We’re tired of [these] narratives. Resilience requires violence in an original form, and again and again in its telling and retelling. One can only be resilient if they continually experience harm.”

One of the most well-known Eyak stories is Anna Nelson Harry’s “Lament for Eyak,” recorded in 1972, which reflects on a time much earlier, on the days of disruptive non-Native settlement in Eyak lands. In that song she grieves the deaths of her aunts and uncles who have left her alone in her homelands, alone on dAXunhyuu beaches. She sings, “why, I wonder, are these things happening to me?” We strain to imagine those losses from our lives lived in the aftermath of such moments of world-changing events. Harry experienced the initial wounding that we now understand as a deep scar of change felt all across Alaska during that time.

However, we also hear Harry’s song as she remarks:

With some children I survive,

on this earth.

…

Around here,

that’s why this land,

a place to pray,

I walk around

…

alone around here I walk around on the beach at low tide.

I survive.

Kelp has been there all along, undulating near the shoreline in families bearing the names we made for it, beaching itself as an offering for food or as other, helpful material. We follow Harry’s words, “that’s why this land, a place to pray….” We walk around on the beach at low tide among the kelp with our children. We survive.

This photo essay is part of the Holding Sway: Seaweeds and the Politics of Form series, funded by UCHRI’s Recasting the Humanities: Foundry Guest Editorship grant.