On Becoming Virushuman: Contemplating Trans-specism and Artificial Humanity during the Coronavirus Pandemic

by

You [humans] multiply until every natural resource is consumed. The only way you can survive is to spread to another area. There is another organism on this planet that follows the same pattern. Do you know what it is? A VIRUSSSSS. Human beings are a disease, a cancer of this planet. You are a plague. And we…are the cure.

—Agent Smith (Hugo Wallace) talking to Morpheus (Laurence Fishburne), The Matrix

The 1999 film The Matrix by directors Lana and Lilly Wachowski takes place in the future ruled by an omnipotent artificial intelligence (aka the Matrix) in an aftermath of an unspecified catastrophe caused by mankind that rendered most of the planet uninhabitable. Humans are blissfully unaware that their bodies have been turned into energy farms while their consciousness lives in a virtual world created by the computer. The few humans, including their leader Morpheus, who have awakened to this reality are trying to free humanity from the Matrix. In the scene quoted above, Agent Smith, who personifies the AI’s attempt to capture and destroy the insurgents, tells Morpheus with apparent disgust that humans should be classified with viruses rather than mammals because rather than “develop[ing] a natural equilibrium with the environment” as most mammals do, humans keep “multiply[ing] until every natural resource is consumed.” His statement reflects the 19th century Malthusian sentiment or the idea that the number of people will soon exceed the earth’s capacity to feed them. We can dismiss Agent Smith’s assertion by pointing out that global capitalism, not population explosion, has inflicted the most damage on the environment. We are, however, in an uncanny situation in which we are tangled up with the coronavirus, just as Neo and Morpheus are trapped in the Matrix. The current pandemic has thrusted upon us a new reality that compels us to redefine our relationship with viruses.

Our UCHRI Residential Research Group was convened under the theme Artificial Humanity. As a scholar of feminist science studies, my approach to this theme is to analyze “humanity” as a material-semiotic construct. The concept of artificial humanity reflects human exceptionalism predicated on a “human” that is separate from everything that is not human. The way “humanity” has historically been rejected for various groups of people is a testimony to how the concept also embodies white heteropatriarchal colonialism. Deconstructing the “human,” therefore is a feminist endeavor, which I try to do in this essay using the coronavirus pandemic as the launching pad.

Becoming COVID-19

The coronavirus is a material-semiotic construct of this particular moment we live in. One unique element is that the virus is becoming closer and closer to us. We are used to being told that infectious agents such as viruses and bacteria attack our bodies and that our immune system is the brave soldiers that strike our enemies and protect us. As the pandemic spreads, the public is learning more about human/virus entanglements, which is destabilizing the Western worldview founded on hierarchical dualism and individualism. The coronavirus morphs into something bigger as a result.

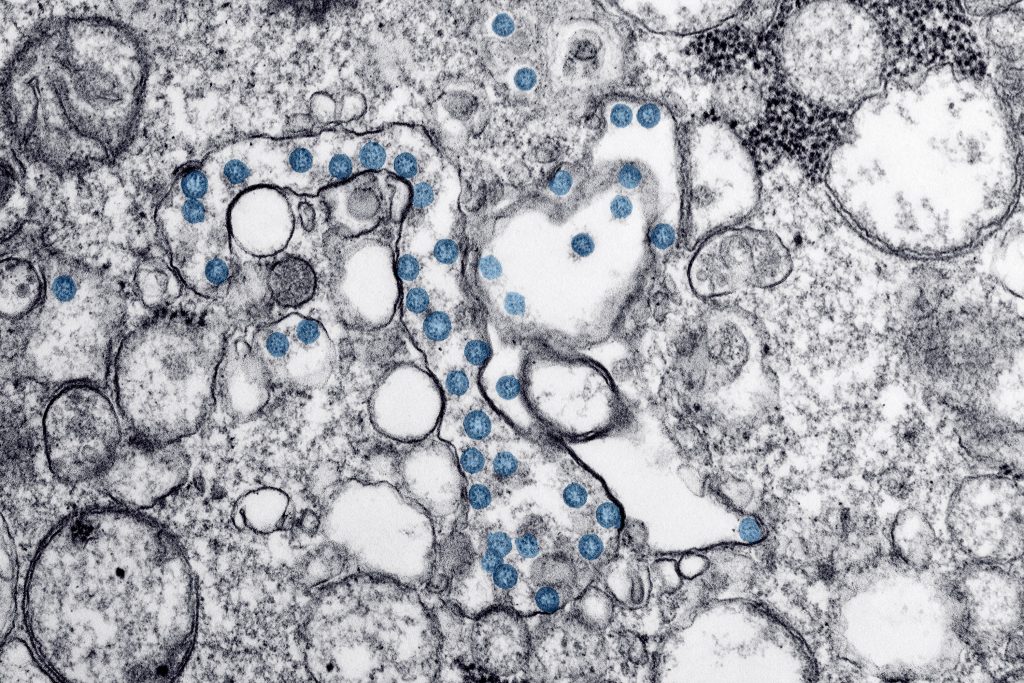

Viruses have a very simple structure made of a protein shell containing genetic information (RNA). They cannot move, metabolize, or reproduce on their own. They lay dormant until they encounter a host that has cells that can bond with that particular type of virus. In the case of Sars-COV-2, the coronavirus that is responsible for COVID-19, has a crown-shaped protein on its shell that matches the structure of a common receptor found on the surface of various types of human cells. When the coronavirus enters the human body through the respiratory system, it attaches to one of these protein receptors, upon which the host cell will bring the virus inside and by breaking it down lets it release its genetic material. The host cell’s regular biomachinary then replicates the viral RNA as well as the proteins coded in its genes including components that make up the virus’s shell. New viruses get assembled inside the host cell, from which they are secreted by the millions. Some of them will go on to be replicated in more host cells; others will be expelled out of the body through the respiratory system and enter other humans to repeat the process. As a Washington Post article suggests, Sars-CoV-2 “functions through us.” When viruses “become intertwined with” our cellular machinery, we become merged with the virus.

“As our bodies become integrated with the virus, our minds have followed. We wear facemasks and keep six feet away as a result of having learned to see other people as viruses…Materially and affectively, this is how we become the virus, and the virus us.”

Feminist theorist and disability scholar Mel Chen points out that when an environmental toxin affects humans, an inanimate material becomes a kind of a subject whilst the human, normally considered the most animate in the animacy hierarchy, falls down the ladder and become an object of toxicity. Humanness and (in)animatedness are thus not stable categories. Chen also notes that “animacy and its affects are mediated…by how holistically you are interpreted and how dynamic you are perceived to be.” To this end, many media reports animate the coronavirus by personifying it as a sneaky operative that “hijacks our cells” with a “certain evil genius” and “finds easy purchase in humans without them knowing.” The more the coronavirus is conceived as a full agent with dynamic subjectivity, the stronger our affective responses become. As “animacy hierarchies are simultaneously ontologies of affect,” the more emotional engagement we develop with the virus, the more animated it becomes. Meanwhile, the discourse of the malicious virus describes the host as unsuspecting, passive, duped and exploited, silencing human agency. Moreover, we are learning that acute symptoms and deaths in COVID-19 patients may be the result of the immune system attacking the cells of our organs. The story of the immune cells that can distinguish the “self” from the “non-self” is over.

As our bodies become integrated with the virus, our minds have followed. We wear facemasks and keep six feet away as a result of having learned to see other people as viruses. We have also come to view ourselves as latent viruses, and refrain from visiting elderly parents and people with underlying health conditions or compromised immune systems. Materially and affectively, this is how we become the virus, and the virus us. With the boundary between the virus and the human broken down, we are now virushumans.

Organismic Intelligence

One might argue that viruses and humans are still nowhere close to each other. The thing is not even alive, let alone have a brain! We tend to associate with species that appear to have brain activities that resemble humans, including apes that can learn to use tools and recognize words, dolphins that seem to have their own language, and dogs that sacrifice their lives to save their owners’ toddlers from danger. Most of us, however, feel very little affiliation with a single-cell organism like bacteria or a virus. Yet, these microorganisms and minute non-organisms play significant roles in our bodily functions including the brain.

Intelligence is typically considered something that is unique to humans. Artificial intelligence therefore was a logical place for our research group to begin our exploration of artificial humanity. We viewed Ex Machina, a 2014 film by Alex Garland about a highly advanced humanoid AI, Ava, who acts so convincingly as a young woman that Caleb becomes emotionally involved in her. Although Ava as a humanoid physically resembles humans, an AI does not have to have a body when the focus is on “intelligence.” Essentially the question behind an AI is: “can we make a machine do everything that a human brain does?”

This brain exceptionalism is another reflection of Western dualism, which defines the mind and body as opposing concepts. The mind is associated with maleness, rationality, being in control, and technology, whereas the body is seen as secondary to the mind and is linked to femaleness, emotion, being out of control, and nature. We have also been taught that the brain is an organ that is individualized in each human and works like a command center that is by far the most developed among all the species on earth. Yet as we learn more about our symbiotic relationship with the human microbiome, the notion of a uniquely intelligent human brain becomes tenuous.

To begin, a human body consists of more than 9 million bacterial genes and only 23,000 human genes. More than half of the cells in the human body belong to bacteria, who help ward off pathogens, digest complex carbohydrates, produce mucus in our nasal passage, lubricate pulmonary tissue, and more. The human body is not an independent entity, but a holobiont, or a symbiotic system consisting of complex, multiple, and evolving collaborative relationships with microorganisms. Advanced genetic sequencing is revealing more and more trans-species entanglements, blurring the human/non-human boundary.

“The idea of artificial intelligence currently does not recognize that we are a trans-species being because it assumes that there is an entity that is isolatable as a human…As for the pandemic, we cannot overcome it by thinking against the coronavirus. We need to think with it….”

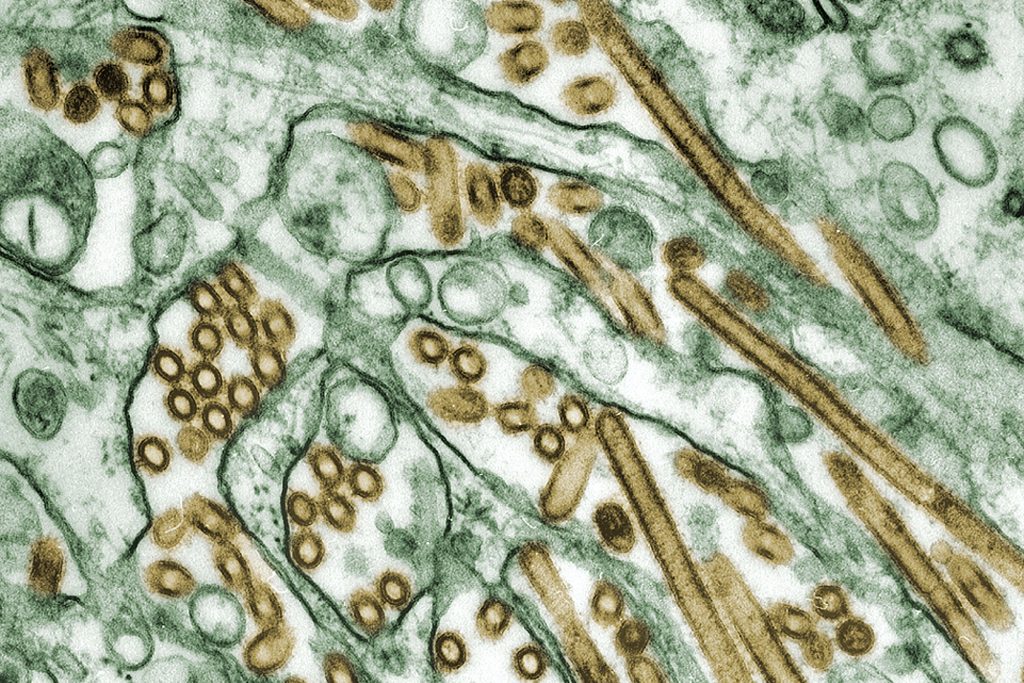

Less well known compared to the human microbiome is the human virome. Viruses are ubiquitous in the human and mammalian gut. Much is still to be learned about their specific roles. We know, however, that some bacteria need viral symbionts to perform its unique digestive function. Some viruses work directly as symbiotic bacteriophage in the stomach that blocks bacteria from moving to other parts of the body where they can cause harm. Furthermore viral genes are found in mammalian genes including ours, indicating that viral symbionts were part of the evolutionary process. An essential gene for the establishment of the placentas, for instance, shows marks of endogenized virus genes. A study has also shown that HIV-positive patients who are also infected with the hepatitis G virus shows slow disease progress. Human lives, thus, have been intertwined with viruses most likely since the evolutionary beginning.

There are also scientific grounds for arguing that the mind/body dualism cannot be upheld. Humans are born to become a holobiont. But its initial bacterial colony formed on a newborn plays an especially important role in setting our lives on its path. Bacterial symbionts affect the newborn’s development from digestive and immune to neurological systems. Our brains, in other words, were nurtured by bacterial symbionts. In adulthood, our gut bacteria produce neurotransmitters that cause changes in the brain, altering our mood, anxiety, and motivation. Researchers are beginning to consider the microbiome-gut-brain axis and how “mental health is not narrowly located in the head but is assimilated by the physical body and intermingled with the natural world.” Brain cells are only part of the total organismic “intelligence,” which is a product, not only of the entire holobiont composed of human cells genes and bacterial and viral symbionts, but also millions of years of evolutionary process.

Agent Smith was not entirely wrong about human affiliation with viruses. As for an AI being “the cure” to the problem of this planet, he may be wrong. The idea of artificial intelligence currently does not recognize that we are a trans-species being because it assumes that there is an entity that is isolatable as a human. Without recognizing our entangled relationships with “others,” be it people of different gender, race, ethnicity, and nationality or another living or non-living thing, we will probably not find a “cure” for mutual cohabitation on this planet. As for the pandemic, we cannot overcome it by thinking against the coronavirus. We need to think with it as Donna Haraway advocates in sympoiesis.

This essay is part of the focal series, VIRUSHUMANS, coordinated by UCHRI’s Spring 2020 RRG on Artificial Humanity.