Shifting the Horizon: An Interview with Guest Artist Rebeca Méndez

by

Rebeca Méndez spoke to UCHRI Interim Director Julia R. Lupton about her work on migration and its place within the Institute’s Refuge and Its Refusals.

“Scientists, artists, indigenous peoples, migrants from all over the world—we’re beginning to talk to each other about a problem, and we are ‘staying with the trouble,’ as Donna Haraway puts it.”

Thank you, Rebeca, for agreeing to be our guest artist for the UCHRI 2022-23 initiative, Refuge and Its Refusals. We are excited to feature images from your Circumsolar Migration series, which uses the Arctic tern to consider broader questions around human migration, environmental degradation, and the nature of refuge in a changing world. Can you tell us how that project came about?

Circumsolar Migration 1 began serendipitously. I had an artist’s residency in Skriðuklaustur, in the Fljótsdalur Valley near Egilsstaðir, in the east of Iceland, for the Gunnar Gunnarsson Institute. I began learning about the Arctic tern, which has the longest migration of any creature in the world. It goes from the Arctic to the Antarctic and back again. It’s a very tiny seabird, weighing only four ounces, and it sees the most daylight, because it’s always pursuing the sun. In 2012, ninety percent of the chicks were dying of starvation. The seas around Iceland are warming up enough for the migrations to shift. All migration shifts when just one element changes.

I’m using bird migration to understand how other species are dealing with climate change, but also as a metaphor for all the crises in migration happening today. As an immigrant myself, I’m very interested in issues of migration, whether it is of animals, people, or the currents that move our planets. The geopolitics of our time involve closing our borders and allowing people to die rather than really understanding what the health of our planet, and the health of all of our communities, really is. What will give us clarity on how we evolve as human beings? And how do we survive as a species?

In the image we’ve chosen to orient us in Refuge and Its Refusals, you decided to rotate the horizon vertically. What does that mean to you?

For Circumsolar, Migration 3, I was filming in Látrabjarg, the largest bird cliff in all of Europe, on the western end of Iceland. Puffins, northern gannets, razor bills—it’s a super highway of bird migration. I saw the birds going up and down, up and down, and I became disoriented myself as I followed the birds in flight. I turned the camera sideways and I saw the horizon line differently for the first time. There’s something about the horizon line in a landscape, a seascape—we’ve seen it so many times that we don’t see it anymore.

“Turning the horizon revealed that code, and abstracted it, making us open to the code of migration.”

I’ve always been interested in the moment where the sea and the sky meet. Blurring that line also blurs the dichotomies in our world. I not only saw the horizon line with new eyes, but I also saw migration very differently. The horizon was literally going like the Arctic tern, from north to south, from above to below. It almost felt like a code, a migratory code. I learned a lot about the different ways in which birds migrate, and how they orient themselves, whether it is through landmarks, through smell, through magnetism. And so turning the horizon revealed that code, and abstracted it, making us open to the code of migration.

I’ve always been interested in the moment where the sea and the sky meet. Blurring that line also blurs the dichotomies in our world. I not only saw the horizon line with new eyes, but I also saw migration very differently. The horizon was literally going like the Arctic tern, from north to south, from above to below. It almost felt like a code, a migratory code. I learned a lot about the different ways in which birds migrate, and how they orient themselves, whether it is through landmarks, through smell, through magnetism. And so turning the horizon revealed that code, and abstracted it, making us open to the code of migration.

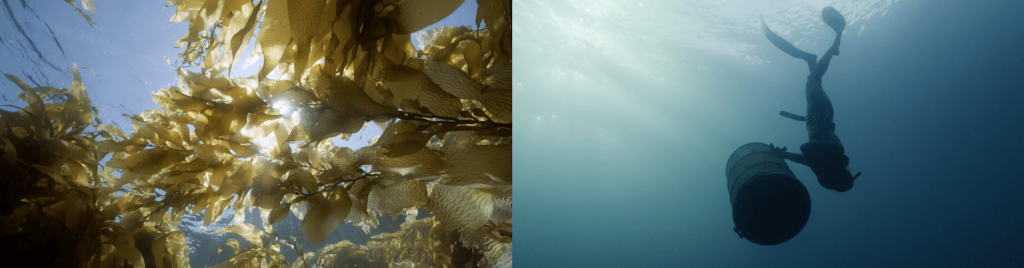

You have a beautiful and compelling exhibition, The Sea Around Us, on view at the Laguna Art Museum (Nov 4, 2022-Feb 5, 2023). This 360-degree video installation, shot underwater off the coast of Catalina, creates an immersive refuge for viewers. Sitting in the darkened room in a soundscape enriched by Tongva and Acjachemen voices, we are asked to commune with abalone and contemplate with kelp while also confronting the reality of DDT contamination off our coasts. Can you tell us about this new work?

In The Sea Around Us, I wanted to focus on the multiple voices of the Pacific Ocean, our beautiful front yard. I was struck by Rosanna Xia’s report for the LA Times about the illegal dumping of DDT barrels right off Catalina Island. The piece itself happens all underwater. I collaborated with folks from the Acjachemen and Tongva tribes; I wanted to understand how their ancestors worked with the sea, related to the sea.

Scientists, artists, indigenous peoples, migrants from all over the world—we’re beginning to talk to each other about a problem, and we are “staying with the trouble,” as Donna Haraway puts it. Staying with the trouble is the key to accepting that we are intricately connected.

What does the word refuge mean to you?

What does the word refuge mean to you?

“The best refuge we can have lies in reciprocity, where we act with respect and responsibility toward each other.”

As an artist, as a human being, I understand refuge as both exterior and interior. We’re always so lucky, so grateful, that we have a roof over our heads. But refuge really means finding a place where you can actually have the integrity of your own human rights, where nothing is violated, nothing is fragmented. Common kindness, the commons, that to me is also a refuge. Where we are in community, we are for each other. The best refuge we can have lies in reciprocity, where we act with respect and responsibility toward each other. And this reciprocity in refuge should be extended to all beings, not just humankind, but also plants and animals. Being able to express and hold refuge for all of us: that’s what being alive and being part of this living world is.