What We’re Reading: Civil War

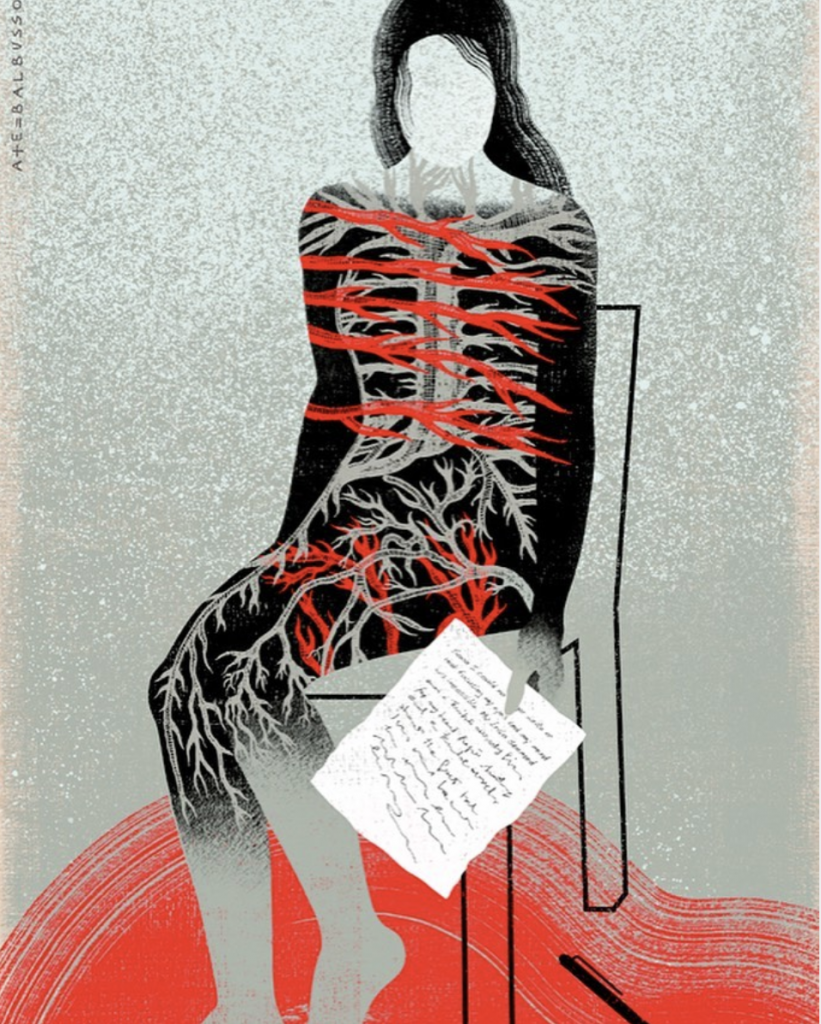

Alison Annunziata, Research Programs Manager

When I think of civil war my mind often turns to those battles invisible to the naked eye. Illustrations by Anna and Elena Balbusso, combining fantasy, futures, fixation, and failure, brings into relief these subtle wars—wars between lovers, the war each of us has with ourselves, and, in the case of their piece, “Autoimmunity,” the war inside the body, which the artists beautifully draft as asphyxiation via venous barbed wire. Autoimmunity is more than a biological metaphor for our culture at large (as Derrida once proposed); it is a predictable outcome and direct product of a culture racing towards self-destruction. A world wherein like not only determines like, but, in a perverse case of mistaken identity, like attacks like. Healthy cells are supposedly mistaken for disease and an aggressive attack is launched in error. But maybe the body’s system got it right. Like a wolf in sheep’s clothing, like a call coming from inside the house, autoimmunity plays with the unpredictability and imprecision of the line demarcating friend from foe—for me, a defining feature of any civil war.

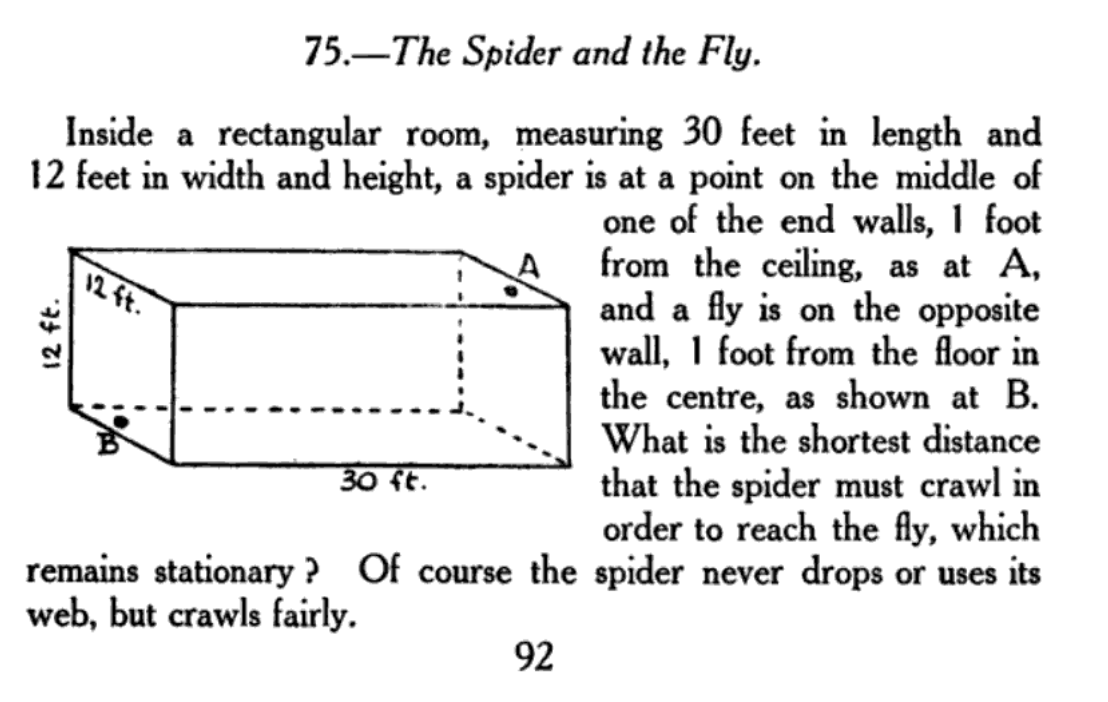

Anirban Gupta-Nigam, Postdoctoral Scholar

One of the two images above is from a book, The Canterbury Puzzles and Other Problems, published in 1919 by English mathematician Henry Dudeney. The second, a photograph I took after a swim one summer morning in 2019. (No prizes for guessing which is which.) For some time now, I’ve been quietly preoccupied by the problem of the spider and the fly as a question of incommensurability and world-building. What Dudeney poses as a mathematical question of measure, others have theorized as a systems problem. So, John Holloway begins Change the World without Taking Power by reflecting on the unfairness of a spider asking a fly to dispense with its negativity: “… there is no way the fly can be objective, however much she may want to be: ‘to look at the web objectively from the outside—what a dream,’ muses the fly.” The web is capitalism. Giorgio Agamben approaches the matter from another direction, suggesting: “The two perceptual worlds of the spider and the fly are absolutely uncommunicating, and yet so perfectly in tune that we might say that the original score of the fly … acts on the spider in such a way that the web the spider weaves can be described as ‘fly-like.’”

Where Holloway envisions the spider’s web as a trap, Agamben positions it as an expression of “the paradoxical coincidence of this reciprocal blindness.” In this latter view, the web is an articulation of heterogeneous worlds intimately worlded by creatures not fully aware of the worlds they are worlding. As our world spins into near-oblivion, I can think of no better descriptions of civil war than these two radically distinct interpretations of the same relation. And as aware as I am of the incessant, enthusiastic brutality of webs spun in capitalist dreamworlds, I lean, nonetheless, into an image of the web as a world built on “reciprocal blindness,” with all the precarities such a world gives form to.

Eric Newman, Research Communications Manager

I noticed over the holiday break and in the many weeks since that I keep returning to The Atlantic’s special issue How To Stop A Civil War (December 2019). It’s one of the few magazines I’d physically marked up as I was reading last year, noting passages to return to later as well as those with which I disagreed, my marginalia attempting to assess why. Two pieces stuck out to me, both for the way in which they spoke so immediately to our present moment, but also for how they point to the larger, systemic conflicts that underpin my thinking about “civil war.” The first was Jonathan Haidt and Tobias Rose-Stockwell’s The Dark Psychology of Social Networks, which argues that the extreme compression of time and information on social media, as well as the prioritization of attention-generating content (usually in the form of appeals to extremism and outrage), fuse to create an ideal environment for fomenting rancor, misunderstanding, and harm. The second was Megan Garber’s Sorry, Not Sorry: Why Public Figures Stopped Apologizing, which gets at the ways in which a humble apology has been weaponized by today’s politicos, suggesting that their reticence to reconciliation has trickled down to the granular relationships between the masses and their everyday engagements with one another online and IRL. If our media and the social environment that it shapes have warped the logics of social relation, perhaps only by restoring the basic humanity of our bonds with others can we truly stop a civil war.

June Ke, Graduate Student Researcher

Be strong like ice.

Be fluid like water.

Gather like dew.

Scatter like mist.

These four principles, poetic and evocative, drive the Water Revolution, better known as the Hong Kong protests of 2019-2020. Deriving inspiration from Bruce Lee’s martial arts dictum for movement, “be like water” is a metaphor for fluidity and responsiveness in combat. It doubles as an organizing strategy for the protestors, who adopted a leaderless structure and remained on the move to evade capture by the police. In the midst of the movement, Daniel Tsang, librarian emeritus of UCI, has been archiving and sharing pictures from his time as a visiting scholar at The Chinese University of Hong Kong. One of the most heartening pictures of the protests was taken at an improvised canteen set up by the protestors at CUHK. The food was donated by the public and cooked by volunteers for everyone barricaded inside the campus. Food is a mundane blessing, but even in the midst of civil antagonism, one needs nourishment for the body and soul.

Kelly Anne Brown, Associate Director

Jogging through the civil war battle lines of my working class Costa Mesa neighborhood. Just after the 2016 elections “Bash Fascists” appeared on the sign for the local residential-esque motel. This is the motel—unremarkably similar to many across the nation—that offers rooms and extended stays at a rate that the newly homeless can afford. STAY SMART: at least for the moment. But just two blocks away, etched into the cement, is the trio: KKK, 666, and a swastika. For a neighborhood with surprisingly little gang graffiti, these marks stand out. A mixed neighborhood, there is a contestation among those who belong, and those who don’t. But while the “Bash Fascists” was cleaned away, the marks of white supremacy remain, part of the sidewalk I jog on almost every day, and prompt me to regard my neighbors with suspicion.

Shana Melnysyn, Research Grants Manager

The freeways, roads, and parking lots of Southern California are warzones. I have orchestrated my life here as carefully as possible to try and avoid the madness, but it still consumes me: cortisol still pumps into my veins; carbon dioxide still pumps into the air. I sit in traffic just to leave my place of work, to make it 7 miles to my home. I fight for a parking spot at the yoga studio where I go to decompress from the monotonous lifestyle that allows me to pay off my debts, because I have to pay them. I grasp for meaning. Collectively, we pay what we owe, all the while incurring much more serious debts. We pay them with our souls, our health, our vitality. The time for refusal, for deprogramming, and for breaking chains is upon on us. Clogged freeways full of angry, miserable, lonely worker bees are its harbinger. The war seethes within us, swirling in our suffocating car interiors, rising off the pavement in waves. Images replay in millions of minds—what we must do, and what we could be doing; what we believe, and what we gawk at in disbelief. Nervous thoughts ricochet off metal and concrete on the 405, in the mounting heat. They murmur cacophonously but do not cohere.