Auto-Immunity in the Age of COVID-19

by

This work-in-progress, which is extracted from a longer piece of writing, reflects on the pertinence of Derrida’s thought of the autoimmune relation to the inhuman other to the global political economy of COVID-19.

Much of the early discursive analysis of COVID-19 as an existential, social, and political-economic phenomenon is informed by the critique of the anthropocene.1 The critical analysis of the anthropocene was popularized in the social sciences and the humanities by Dipesh Chakrabarty and Donna Haraway among others. Simply put, this analysis attempts to show that the human subject is not an autonomous being that has transcended the natural world but is, as one among many biological species and geological beings, entangled with other biological and geological beings. Its ethico-political message is that we have done irreparable damage to other life forms and the environment and climate by ignoring this entanglement. Echoing the Frankfurt School’s critique of instrumental reason, it is suggested that the view of human beings as free rational agents who are superior to other beings has led us to treat other beings as objects to be exploited and dominated. With climate change, this domination has reached a point of crisis that now threatens human existence. Hence, we need to question the privileged status of the human being and rethink its relations to other beings differently. As Chakrabarty puts it, “climate change is an unintended consequence of human actions and shows, only through scientific analysis, the effects of our actions as a species. Species may indeed be the name of a placeholder for an emergent, new universal history of humans that flashes up in the moment of the danger that is climate change.” Haraway rejects the anthropocene paradigm altogether because it privileges human agency at the expense of the agency of other species and the environment on the human species. She suggests that we should begin with multispecies worlds and that we all become-with other species: “Companion species are relentlessly becoming-with…[S]pecies of all kinds are consequent upon worldly subject- and object-shaping entanglements.”

This sort of discourse has influenced the public understanding of the virus. Although the first detected case of the virus was in a live animal wet market that sold wild animals for consumption in Wuhan, the People’s Republic of China (PRC), it is argued that the larger conditions that caused the trans-species migration of the virus or zoonotic transfer (probably from bat excrement to the pangolins that were sold in the market to humans) is the damage done to the world’s ecosystems in the anthropocene era by deforestation and other disruptions to the natural environment. These disruptions have driven animal species from their natural habitats and forced them into contact with other species, thereby facilitating the transfer of micro-organisms from their natural hosts.

“This idea of what is naturally proper human conduct in relation to other species is a direct consequence of the conservative value of presence, or more precisely, co-presence that governs anthropocene and chthulucene discourses.”

Axiomatic to this argument is the moral idea of a naturally proper relationship of the human species to the environment and other animal species that we have violated in the anthropocene era. Thus, one commentator notes: “This viral outbreak is a sign that by going too far in exploiting the rest of nature, the dominant global culture has undone the planet’s capacity to sustain life and livelihoods…The current pandemic is just one aspect of the human-made planetary crisis known as the Anthropocene; runaway climate change and biodiversity loss are others—and all are connected. COVID confronts us with a civilizational crisis so immediate and so severe, that the only real strategy will be one that can reach into and heal the web of life.” Second, the consumption of exotic wild animals is another unnatural relation of humans to other biological species. It has created an artificial setting that enables the migration of the virus to human hosts. Other commentators note: “We are increasing transport of animals—for medicine, for pets, for food—at a scale that we have never done before…We are also destroying their habitats into landscapes that are more human-dominated. Animals are mixing in weird ways that have never happened before. So in a wet market you are going to have a load of animals in cages on top of each other.” “The capturing, slaughtering, selling/trading and consumption of wildlife are to blame, not the animals themselves.” The consumption of wildlife is, however, only the most extreme case of human-animal intercourse that facilitates the transmission of zoonotic disease. Research shows that “the most frequent locations of transmission were in and around human dwellings and in agricultural fields, as well as at those interfaces with occupational exposure to animals: like. [sic] hunters, laboratory workers, veterinarians, researchers, wildlife management, as well as zoo and sanctuary staff. Most of these high-risk interfaces have been driven by factors related to global animal species abundance.”

This idea of what is naturally proper human conduct in relation to other species is a direct consequence of the conservative value of presence, or more precisely, co-presence that governs anthropocene and chthulucene discourses. They detach the privilege of being and becoming from the human subject only to reattach it to non-human beings that are co-present and originally connected with human beings. For example, Chakrabarty’s attempt to undo the distinction between human history and natural history privileges nature as a present substance in which all beings subsist. Haraway’s string-game model for becoming-with is a representational figure for multiple co-presence. These discourses merely extend the privilege of original presence to non-human beings without ever posing the question of the giving of being and the radical alterity of that gift. Consequently, they also display a complacent and even self-righteous piousness in their polemical dismissal of others for not recognizing the substantial presence of nature or the co-presence of non-human life-forms.

Certain types of human sociality or conduct in relation to animals are contra nature. This is therefore an ethical discourse about the proper conduct of human beings, about the proper of humankind: how the human species ought to behave in a manner that would be appropriate to its being as one among many biological species. Human beings are regarded as social animals who also a part of nature and live with other natural species. Types of human-animal sociality or inter-species interfaces that are improper according to nature have unnatural consequences for animal species and anti-social and even anti-human repercussions for human social existence.

This discourse of the proper is unavoidable. It is structural to the concept of organic life itself. By definition, the organism is a being that can maintain the integrity of its proper self as an organized and self-organizing being in its exposure and intercourse with outside forces. At the level of global political economy, this discourse of the proper is at work when the U.S. state and society elements place the blame on China as the origin of the virus and identify its national culture with the unnatural practice of consuming wild animal species. For example, when President Trump refers to the virus as the Chinese virus, unnatural human conduct is racialized by implying that these dietary practices are Chinese and, more broadly, Asian. This is not merely the racial nationalism of the Trump administration. Bill Maher, the HBO host, noted that the virus had nothing to do with Asian Americans but “it has everything to do with China….We can’t afford the luxury anymore of nonjudginess towards a country with habits that kill millions of people everywhere because this isn’t the first time. SARS came from China and the bird flu and the Hong Kong flu, the Asian flu. Viruses come from China just like shortstops come from the Dominican Republic. If they were selling nuclear suitcases at these wet markets, would we be so nonjudgmental?” The erection of all kinds of borders such as trade barriers and immigration barriers are attempts at asserting a certain vision of the sovereign autonomy of the national organism. Social distancing goes against the sociality of humankind, but it is necessary to rectify the unnatural turn of events. And the first efforts at social distancing involve distancing from political others that are the source of threats to the national population’s biological well-being.

“Accordingly, ontological friendship is the steady support of being-there for the other and not an intrusive over-caring or intervention that hastens to influence, direct or prescribe the other’s essence.”

The fundamental status of the proper remains intact in the discourse of the chthulucene despite its bravado rhetoric of messiness and openness. For the chthulucene is all about kinship and therefore sameness with other animal species. Consequently, it enlarges the proper collective organism so that it extends beyond human beings to include all biological beings in a harmonious accord, even if or especially because this inclusion involves the mediation of biomedical technologies as in Haraway’s example of the development of Premarin from the harvesting of mare’s urine and the feminist activism. At heart, chthulucenic responsibility repeats the platitude that we are dependent on and co-implicated with other animate and inanimate beings that thereby exert an “agency” on us. This point, however, is a truism. All finite material beings qua living beings need to maintain a relation to other beings simply because breathing and the absorption of nutrients from outside the organism are necessary to the life process. As Marx already noted, the human metabolism with nature is such that nature is the inorganic body of humankind, man’s body outside his organism proper: “species-life…consists physically in the fact that man, like animals, lives from inorganic nature….Nature is man’s inorganic body [unorganische Leib], that is to say nature in so far as it is not the human body. Man lives from nature, i.e. nature is his body, and he must maintain a continuing process with it if he is not to die. To say that man’s physical and mental life is linked to nature simply means that nature is linked to itself, for man is a part of nature.” Haraway repeats the same argument with a hippie, flower-power, we-are-all-part-of-the-whole-earth elemental feelgood vibe, updated for our postmodern technological age through the motif of the cyborg: “There is no innocence in these kin stories, and the accountabilities are extensive and permanently unfinished. Indeed, responsibility in and for the worldings in play in these stories requires the cultivation of viral response-abilities, carrying meanings and materials across kinds in order to infect processes and practices that might yet ignite epidemics of multispecies recuperation and maybe even flourishing on terra in ordinary times and places.”

But these discourses take for granted the simple fact of life itself. They take for granted that we are worldly beings, that we are (in a world) at all. It seems obvious to point out that we can only become-with other beings or be entangled with them because we and they already are in such a way that we are open to and have access to each other. Indeed, the term “entanglement” presupposes the stringing together of various beings, where the string is a figure for relating or connecting separate terms. Despite Haraway’s repeated use of the term “worlding,” she completely begs the ontological question of worldliness and worlding: what propels beings into entanglement and makes relating or connecting to other beings possible? The term worlding (welten) is of Heideggerian provenance. But although Heidegger’s and Derrida’s critique of anthropologism predate the anthropocene turn by many decades, the latter has never engaged with their thought. Indeed, Haraway dismisses Heidegger with an off-the-cuff remark: “Finished once and for all with Kantian globalizing cosmopolitics and grumpy human-exceptionalist Heideggerian worlding…Never poor in world, Terrapolis exists in the SF web of always-too-much connection, where response-ability must be cobbled together not in the existentialist and bond-less, lonely, Man-making gap theorized by Heidegger and his followers.”2 This is unfortunate because the critique of the anthropocene and Haraway’s alternative discourse of the chthulucene take for granted something that Heidegger and Derrida, one of his followers, do not: that living beings and other beings first have to be before they can be entangled.

The exploration of this question led Heidegger to develop an account of the ontological friendship of phúsis for all beings as part of his larger critique of anthropologism. Discourses of the anthropocene and the chthlucune are either ignorant of this critique of anthropologism or have repressed it despite its obvious relevance to their concerns. In his 1943-1944 seminar on Heraclitus, Heidegger argues that phúsis itself is philía, which he translates as the giving of favor (Gunst) and friendship (Freundschaft). Phúsis is conventionally translated as “nature” because of its interpretation in Roman thought as natura (birth or origin) on the basis that the coming into being of all beings is like the generation and course of natural phenomena such as the genesis and growth of plants from seed to flower and fruit or the rising of the sun. Heidegger argues that this interpretation obscures the true character of phúsis.3 It generalizes the naïve experience of natural phenomena to describe the fundamental ground of such experience: the coming-forth into presence and phenomenality such that there is something instead of nothing. This coming-forth is the condition of there being anything like nature: “phúsis names that prior emerging within which earth and sky, sea and mountain, tree and animal, human and god emerge and thereby show themselves as what emerge, so that they, in light of this emerging are known as ‘beings’. What we call ‘natural processes’ first became visible to the Greeks in the way of their emerging within the light of phúsis.”4 The translation of phúsis as natura is a metalepsis that substitutes a dynamic process of giving with a pre-given substance (nature) that is generated by the giving.

Accordingly, Heidegger rejects the conventional translation of Heraclitus’ Fragment 123, phúsis kruptesthai philei as “nature likes to hide itself” because the characterization of philei as the predilection of nature qua subject in the sense of “children like to snack” turns phúsis into a metaphysical subject. He argues that we should understand philei as the affordance of a favor in that something is brought into being where there was previously nothing. He translates the fragment as “emerging to self-concealing gives favor [das Aufgehen dem Sichverbergen schenkt’s die Gunst].” For Heidegger, this relation of generation and withdrawal between phúsis and all beings, where phúsis distances and withholds influence is best characterized by friendship. Let us quote at length:

We now translate the philein in Heraclitus’s saying as “to give favor [die Gunst schenken]”. In doing so, we understand favor in the sense of the originary granting and bestowal [des ursprünglichen Gönnens und Gewährens], and therefore not in the secondary meaning of ‘benefit’ and ‘patronage’. This originary granting is the bestowing of what is owed to the other because it belongs to the other’s essence, insofar as it bears that essence. Accordingly, friendship, philía, is the favor that grants to the other the essence that the other already has [die Gunst, die dem anderen das Wesen gönnt, das er hat], and in such a way that through this granting the granted essence blossoms into its proper freedom. In ‘friendship,’ the essence that is reciprocally granted is freed to itself. Neither excessive solicitude nor even ‘jumping in’ to help in emergencies and dangerous situations is the defining characteristic of friendship: rather it consists in being-there for another [sondern das füreinander Dasein], which does not require any kind of event or proof, and which works by abstaining from exerting influence.

It would be a mistake to believe that such bestowal of essence comes about all by itself, as though ‘being-there [Dasein]’ were here nothing other than something present-to-hand [ein Vorhandensein]. The bestowing of essence requires knowledge and patience, and granting is the ability to wait [ein Wartenkönnen] until the other finds itself in the unfolding of its essence and for its part does not make a big fuss about this discovery of essence. Philía is the granting of favor that gives something that does not at bottom belong to it; this favor, however, must give a guarantee of the other being so that it can remain in its own essence [was ihr im Grunde nicht gehört und die doch Gewähr geben muß, damit des anderen Wesen im eigenen verbleiben kann].5

Ontological friendship is the support of phúsis for all beings in the sense that phúsis enables their being-there. Being-there, that is, being something as opposed to nothing or, better yet, being as opposed to not being, should not be taken for granted the way we take the mere presence of objects for granted. But although phúsis gives every being essence insofar as every being has its own essence, phúsis does not dictate that essence because as a process of emergence that immediately withdraws, it releases and frees every being. Put another way, the essence of the beings that phúsis grants is not originally found in phúsis and does not belong to it and beings are left alone to find and develop their own essence. Accordingly, ontological friendship is the steady support of being-there for the other and not an intrusive over-caring or intervention that hastens to influence, direct or prescribe the other’s essence.

Ontological friendship is not the anthropomorphic imposition of a human subject’s personal lived experiences of friendship onto phúsis. Heidegger rejects the suggestion that Heraclitus attributed a subjective human attitude to objective nature by noting that this argument not only dogmatically assumes that favor and bestowal are the special right and property of the subject but also anachronistically projects the modern ontological determination of the human as “subject” onto early Greek thought. Friendship in the Heraclitean sense is important precisely because it points to an original ground that precedes and exceeds the subject. To the extent that lived experiences and, indeed, life as such originate from phúsis, ontological friendship is the thought of the fundamental foreignness or alterity of human experience. Heidegger observes that because every aspect of experience from the experiencing subject to the experienced object originates from the favor of another, the lived experiences we take for granted as proper to us and our very own “could in their essence perhaps not belong to us [könnte in seinem Wesen vielleicht gar nicht unser Eigentum sein].”

The motif of auto-immunity in Derrida’s later writings takes ontological friendship as its point of departure. He notes that “when Heidegger evokes the friend or friendship, he does so in a space which is not—or no longer, or not yet—the space of the person or the subject, nor that of ánthropos, the object of anthropology, nor that of the psúkhé of psychologists.” Ontological friendship comes from “a region…withdrawn from metaphysical subjectivity.” Ontological friendship is “a minimal ‘community’,” a community prior to all positive community, that is so original that that it is a priori to and more fundamental than Mitsein, the existential being-with other beings that characterizes Dasein. Being-with others already presupposes the emergence into being that is the favor of phúsis.

In Derrida’s view, although Heidegger emphasizes the sense of foreignness that ontological friendship evokes, this friend is not other enough. Heidegger still figures the favor of phúsis through the motif of accord, which he consistently characterizes as a gathering-together. But if being is only given by that which must withdraw and guard itself, then the favor comes from somewhere that cannot be in accord with being in two senses. First, it is that which cannot be together with being. Second, this withdrawal also disrupts and breaks (with) being because it marks the possibility of not being. There is no guarantee that the favor that gives being will continually be given. Hence, being comes from that which is so radically other that it cannot be of the order of being. Yet, there is being only by this favor that simultaneously opens up even as it renders being impossible. For Derrida, this requires “a thought of friendship which could never thrive in that ‘gathering’ (Versammlung) which prevails over everything and originarily accords philía to phúsis and logos.” Such friendship comes out of and from the absolutely other. The affirmation of the radically other friend “does not allow itself to be simply incorporated and, above all, to be presented as a present-being (substance, subject, essence or existence) in the space of an ontology, precisely because it opens this space up.”6 Because its favor cannot be foreseen or anticipated in advance, the radically other friend replaces the certitude of an accord at the very heart of being with the radical undecidability of a “perhaps” that contaminates and overflows being. Perhaps there will or will not be being, perhaps we will or will not be. Being’s constitutive openness to the coming of the entirely other is a vulnerability without defense to whoever or whatever may come.

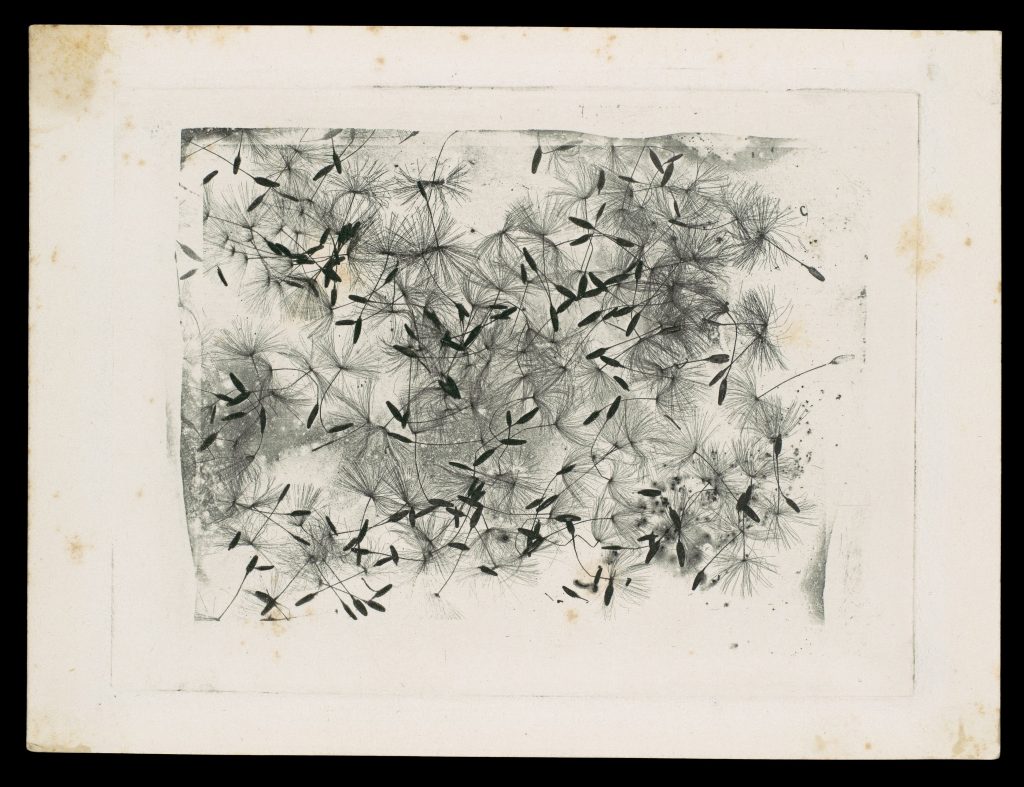

Accordingly, Derrida replaces fraternity and kinship, the conventional socio-political figures for friendship, with a figure from epidemiological discourse to evoke the radically other friend: auto-immunity.

The modality of the possible, the quenchable perhaps, would, implacably, destroy everything, by means of a sort of auto-immunity from which no region of being, phúsis or history would be exempt. We could, then, imagine a time [that would]…resemble nothing, nor would it gather itself up in anything, lending itself to any possible reflection. It would no longer relate to itself…[I]t would not be—in other words, it would not be present—either with the other or with itself…One would then have the time of a world without friends, the time of a world without enemies. The imminence of a self-destruction by the infinite development of a madness of auto-immunity.

In what manner of speaking is auto-immunity an apposite figure for radical alterity as the constitutive (im)possibility of being-with others? Auto-immunity perverts the process of immunity, whereby a body protects itself by producing antibodies to combat foreign antigens. In auto-immunity, Derrida notes, the organism protects “itself against its self-protection by destroying its own immune system.” Because the organism immunizes itself against its own immunity, this is a hyperbolical form of suicide where all sense of self (sui) is destroyed. Similarly, a being that seeks to protect its own being by immunizing itself against absolute alterity does violence to itself because it closes itself off from the condition of possibility of its being, the other that is at the same time itself. At the same time, surrendering to the other is also the loss of being.

“Consider how the curious phenomenality of COVID-19 forces us to confront the auto-immune character or radical finitude of being.”

What is provocative about Derrida’s argument about our auto-immune relation to the radically other is that it extends responsibility beyond humanist universalism such that we are constitutively responsible to the inhuman other. But this kind of responsibility, which is a priori to Haraway’s chthulucenic responsibility, cannot be figured as the accord of kinship. All beings are finite because they are not the originator of their own being. A living being is one among many examples of being. An organism lives and can die because it is finite. It is not finite because it lives and dies. Under conditions of radical finitude, where our being is not given by an absolute being or divine creator, who or what gives being or why there is even being instead of nothing cannot be taken for granted and is inexplicable. Hence, being is a gift of the radically other. The deconstructive re-grounding of Mitsein in radical alterity means that being-with is not only detached from the human being but also no longer anchored in being or coming-to-be. Our openness to this other is more original than our openness to the other beings on which we depend for our continued survival because we can only be and, therefore, be with other beings by being open to a radical alterity with whom we can never claim kinship. At the same time, this vulnerability is also the condition of impossibility of beings and this is why we also need to limit our vulnerability. The living organism’s need to achieve a proper identity and regulate its exposure to the other beings and forces on which it depends so that it can return to itself is an inadequate phenomenal analogue for the structural auto-immunity of all beings to the inhuman other.

Consider how the curious phenomenality of COVID-19 forces us to confront the auto-immune character or radical finitude of being. First, the manner of our emergence into being together with other living beings is the original condition of possibility of zoonotic transfer. Hence, zoonotic transfer is not an original moral sin of the anthropocene. Second, strictly speaking, responsibility to the radically other means that once COVID-19, like any other being, has come into being and emerged into phenomenality, it has a being of its own and a right to be in its own essence. Its jumping from one animal species to another and then to human beings and its ongoing mutation in human beings is part of this right to be in its own essence and to develop according to its own essence. To use a term from Spinoza, this is part of its conatus. It maintains its being by adapting to its environment including the body of its human host and changing its identity. This occurs independently of the human being’s right to be in its own essence, which makes the task of finding a vaccine more difficult. We may be able to track these mutations after the fact with bio-medical scientific knowledge, but the mutations themselves are unpredictable events. Third, creating a vaccine that will give us immunity is essentially an attempt to domesticate the virus’s alterity, to integrate it in the form of antibodies into the proper body of the human organism, for example, by using plasma from people who have already been infected. We willingly open ourselves up to the virus but in a rationally regulated manner so that the virus in a more tolerable and even beneficial form will become part of our proper body. However, this potentially beneficial opening, a conditional or limited hospitality, presupposes the sheer vulnerability of opening, the unconditional hospitality, that exposed us to a virus that threatened our being in the first place. The risk involved in the testing of any vaccine is the clearest empirical example of this aporia.

Ultimately, what is intolerable to us, to any organism and, indeed, to any being is that the undecidability of our opening to radical alterity is structural to our being. No heartwarming kinship with other beings is possible here. We are brought into phenomenality with other beings, some of which may threaten our being and we may not be aware of this until it is too late. But without our unconditional exposure to the inhuman other, we would not be in the first place. Accordingly, like any organism trying to guard its own life, we protect ourselves against an other that is in fact ourselves and we negotiate with our auto-immunity to regulate our exposure and immunize ourselves where we can. This is the aporetic exigency that COVID-19 presents to our lived experience.

This essay is part of the focal series, VIRUSHUMANS, coordinated by UCHRI’s Spring 2020 RRG on Artificial Humanity.

Notes

- See, for instance, James Magnus-Johnston, “Outbreaks in the Anthropocene: Growth Ain’t the Cure,” Ashish Kothari et al, “Coronavirus and the Crisis of the Anthropocene,” and David R. Cole, “What Coronavirus Reveals About the Anthropocene.”

- Haraway may be referring to Heidegger’s characterization of the stone as weltlos and the animal as poor of world (weltarm), but there is no way of knowing since she does not cite any text to support her bravado remark. There is a residual anthropologism in Heidegger’s privileging of human Dasein as the only being whose essence makes it capable of understanding being. But this is not a reason to ignore his trenchant critique of anthropologism, his careful account of Mitsein and his later view of the world as a fourfold. Haraway, who appears unaware of all of this, practices criticism by hearsay.

- For a fuller discussion of Heidegger’s understanding of phúsis, see Daniel O. Dahlstrom, “Begin at the Beginning: Heidegger’s Interpretation of Heraclitus,” and Susan Schoenbohm, “Heidegger’s Interpretation of Phusis in Introduction to Metaphysics.”

- See Martin Heidegger, Heraklit. Der Anfang des abendländischen Denkens Logik. Heraklits Lehre vom Logos, Freiburger Vorlesungen Sommersemester 1943 und Sommersemester 1944, Gesamtausgabe, II. Abteilung: Vorlesungen 1923-1944, Band 55, Heraklit, ed. Manfred S. Frings; Heraclitus. The Inception of Occidental Thinking and Logic: Heraclitus’s Doctrine of the Logos, trans. Julia Goesser Assaiante and S. Montgomery Ewegen.

- Translation modified.

- Derrida’s emphasis.