Irregular Population and the Aporia of Communities

by

This paper arose from the Fall 2017 meeting of UCHRI’s Asia Theories Network, entitled “Island Life.” More papers from the “Island Life” meeting will be released on Foundry over the course of the 2018-2019 academic year.

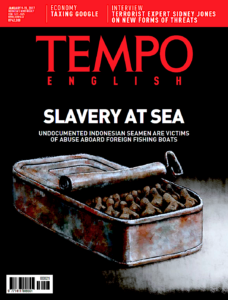

On January 9, 2017, the Indonesian weekly news magazine Tempo featured two startling images on its cover—on the right, for the English version, a half-opened sardine can which is stuffed not with processed sardines, but lined-up troops of grey and drooping human forms; on the left, for the Indonesian version, one hand clutching the barred hatch cover. The title of this issue is “Slavery at Sea,” a story about the slavery practiced by the Taiwanese pelagic fishing industry, which mistreated thousands of Indonesian fishermen who were sold at sea. The images of the sardine can and the barred hatch cover literally and figuratively address the living conditions of migrant laborers in the age of neoliberalism. The canned human lives are packed and accounted purely as a labor force. This simple image links topologically the complex logistics of the entire operating system of the post-modern neo-slavery system, from the Indonesian young men growing up in extreme poverty, sold by the Indonesian local Indonesia Ngau Tau (sponsor), to Indonesian labor employment agency and then to Taiwanese labor employment agency, with very high commission, finally to the Taiwan Distance Water Fishing Company and the owner of the fishing boats. The fishermen on the fishing boat might need to work up to 20 hours a day, sometimes bullied and tortured by the captain, even starved for long hours, and could not get ashore for more than one month. The incidents of riots or even murders, either of the captain or of the crew members, reported by the media are often biased against the foreign fishermen.

The extraction of labor and the maltreatment of the laborers in this form of slavery, unlike the modern operation of slavery, however, are not by force but willed by the laborers voluntarily. Moreover, though blunt and brutal in this particular scenario, this form of neo-slavery in the age of neoliberal market is not exclusive to the pelagic fishing boats, but figuratively illustrates the post-modern slavery system that can be observed in the conditions of the migrant laborers and irregular population in Taiwan or elsewhere, especially the domestic helpers. In this chain of logistics, the local governments of Indonesia and Taiwan as well as local city councils are not necessarily able to dodge their responsibilities. The loopholes in the juridical stipulations concerning the distinction between the employment within or outside of borders are the cause for the fact that the fishermen at sea cannot be protected by Taiwan’s Labor Standards Act. The domestic helpers, though seemingly living in better household conditions, are not protected by the Act either. The employers could easily abuse the domestic helpers in verbal or physical forms, including demanding long hours of work with no holidays, starvation, imprisonment, beating up or even raping. The channel for appeal is often blocked by the agents because they have all signed up the contract and under the control of the agents.

According to the statistics of the Workforce Development Agency, the total number of migrant workers in Taiwan, mainly from Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam and Thailand, had reached up to 706,650 by the end of December 2018. These migrant laborers have filled up the space in various productive industries and social welfare, including agriculture, forestry, fishing and animal husbandry, manufacturing, construction, nursing, and housework. There are also increasing numbers of ‘irregular’ migrant workers, as reported by the National Immigration Agency, and the number of reported runaways or ‘missing workers’ has reached 50,181 in December 2018. The runaway population, mostly escaping from pelagic fishing boats or from oppressive employers, stays with regional Southeast Asian diaspora communities across Taiwanese cities in order to avoid being arrested.

The aim of this essay is to address the question of the complex apparatus of the migrant labor market and the politico-economic-juridical knot that constitutes the techniques of biopolitics in the age of neoliberalism. The sardine can on the cover of Tempo could serve as a trope, indicating the forms of life in East and Southeast Asia in the age of neoliberalism, implicated with the politico-economic conditions of the long histories that went from the age of sea commerce, through the colonial rule and the cold war regime, to the age of neoliberal market.

Several theoretical issues can be addressed here.

I

The double-bind demand from both ends—the need for workers at the end of the labor import country and the financial poverty of the labor export country—co-figures the chain of migrant laborers. But, the politics of citizenship, or even the politics of racist nationalization, justifies the deprivation of the basic civil rights of the migrant workers and segregates the inhabitants in the same cities or even in the same households. The internal border and the invisible communities in the neighborhood, to me, constitute a form of internal coloniality and highlights the paradox of citizenship. This essay wishes to address the issue of the formation and the logic of exclusion in the question of citizenship with the aim to discuss the aporia and the possibility of a community of equals.

II

The status of the agency or middleman and its function in the politico-economic apparatus in the age of neoliberal market, through the help of local government, deserves more analytic attention. The mutation of the role of intermediator—from the chieftain of a local tribe, the Capitan Cina, Shāhbandar (harbor master), compradors, to translators or contemporary human power employment agency—explains the logic of indirect rule practiced in the colonial government. The transformation from the colonial empire, through the post-colonial independent state apparatus, to neoliberal capitalism, however, explains the paradigmatic shift of the economy and the logistics of the mediation of capital and power in the transnational labor market.

III

The emergent new imperialism, particularly through the ideology and discursive elaborations in the mode of post-Confucianism, also needs to be addressed. The hidden logic of the Confucian tributary system could easily surface and permeate in the inter-national and intra-regional relations in East and Southeast Asia. The core-peripheral and dependency relations easily observable in the current strategic plan in the Belt Road Initiative, however, are coated with the contemporary logic of transnational financial cooperation. To theorize the direct and indirect impacts of this emerging geo-economic zoning politics and how it brings forth a new wave of migration is worth noting.

IV

The concept of citizenship needs to be re-considered. “Citizen” originally indicates “burgher” or “city-dweller,” meaning all residents or common people who inhabit in a city or a town. “Citizen,” however, is also associated with the status recognized as a member of a state, with legal rights and obligations, often interchangeable with the status of his or her nationality. Citizens are easily equated with nationals. Moreover, some states deny their citizens with multiple citizenships. It demands exclusive loyalty from its citizens. The question is: why is the status of “citizenship” often defined according to one particular ethnic group while the majority of contemporary states are multi-national composition? The concept of national citizenship can easily preclude citizenship with multiple nationalities. To prioritize national citizenship and citizen right is contradictory to human right, particularly in the cases of migrant workers or irregular immigrants. In some cases, even though endowed with citizenship, some people do not share equal rights in the same city or the same state, especially through the operation of Citizenship Act that differentiates between groups of people who have inhabited in the same societies for over a hundred years or more (Malaysia, Myanmar, Indonesia, India, etc.). In other cases, the government would issue citizenship to some new immigrants for the purpose of increasing the voting population while denying them equal rights to other domains in the society (voting back in India, Malaysia, etc.). Can we redefine the notion of “citizen right” so that it does not exclude city-dwellers with a different nationality or different “citizenship”? Can we treat all people who live here, stay here, work here, as equal citizens and enjoy equal human rights, social rights and culture rights?

The above-listed agenda attempts to contrive a geo-historic specific theoretical framework that could assist us to analyze the logic of internal coloniality in the age of neoliberal capitalism in East and Southeast Asia.