Queer and Trans Studies in Religion in the 2020s: An Interview with Melissa Wilcox

by

Melissa Wilcox (UC Riverside) spoke to UCHRI Research Grants Manager, Sara Černe, for a new Foundry series highlighting the work of the Institute’s recent grantees and the methods, unorthodox approaches, and challenges they have employed and encountered.

“Grant funding has allowed us to dream bigger, to build not what was possible but what was right.”

Tell us about your project: what it is, how it started, where it’s going, and what role collaboration plays in it.

I am working together with academics across the UC system, the country, and the world to launch the first-ever journal in queer and trans studies in religion. The project developed organically: When I came to UC Riverside as the new holder of the Holstein Chair in Religious Studies, one of my projects with the chair funds was to host a conference for scholars in these twinned subfields. Because there isn’t yet a lot of supportive infrastructure at the intersections of trans studies, queer studies, and religious studies, spaces where we can share our work with others in the same subfields—rather than, say, with scholars who study the same religious traditions or the same region of the globe but who don’t have a background in queer studies and/or trans studies—are few and far between.

When I released the call for papers for the conference, my colleague Joseph Marchal at Ball State University reached out to me to ask whether the time might be right for a journal. I’d been thinking along the same lines for a few years, so we began consulting with the broader community of scholars through town hall meetings at the UC Riverside conference and at our national flagship conference for religious studies. We also met with prominent scholars of trans and queer studies in religion, in particular those who were already closely involved with journal publishing in other contexts, to explore the shape the journal would take and how it could best serve our potential contributors and audience.

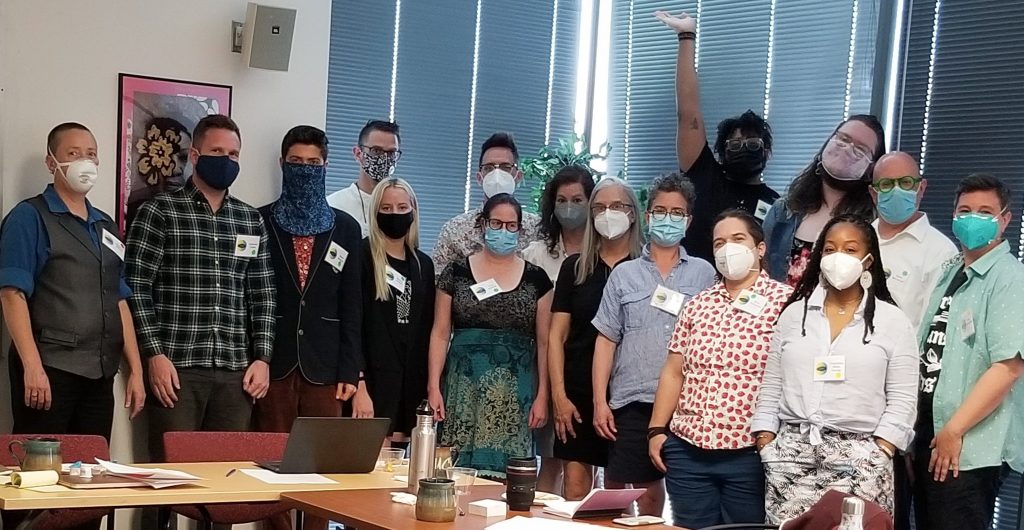

We determined that a fee-free open access journal with a paired website featuring supplemental materials and bite-sized offerings would best serve the range of authors and readers we envisioned for the journal, and Professor Marchal and I began drafting the proposal and talking with potential publishers. We gathered an editorial board, co-Associate Editors who will succeed us as Editors in Chief when our terms are up, and a hand-selected group of emerging, mid-career, and senior scholars to contribute to the themed initial double issue. The May 2022 conference that the University of California Humanities Research Institute (UCHRI) funded gathered these scholars together in person, along with several UC system graduate students, with all expenses paid and an honorarium to compensate participants for their time. The goal was to workshop initial drafts of the papers, review the website that’s taking shape for the journal, and discuss the journal’s future directions.

Can you share why open access is important to you, especially in your field, and discuss some of the institutional challenges you’ve encountered and how you’re addressing them?

Open access publishing was initially introduced in order to make academic work more widely available outside of academic circles; in some countries it’s mandatory for scholars doing research funded by taxpayers to make the results of that research available to everyone. In our field, making this work accessible can literally be a life-or-death concern: Someone coming to terms with their gender, their sexuality, and their religious tradition might look for information online, for instance, and if our work is all inaccessible then the first resources they might find could range from broad platitudes at best to outright, detailed, and apparently solidly grounded hatred at worst. Trans and queer people of all religions, including those practicing traditional and indigenous lifeways and those who consider themselves spiritual, deserve access to leading-edge voices in these areas. So the public access angle is a very important one for us, and is why we’re also developing a companion website for the journal that will feature materials that can be used in classroom settings or quickly digested on a subway ride.

Even more important to us, however, is fee-free open access. As many of your readers already know, publishing does cost money even for a not-for-profit university press. Someone has to pay the salaries of the editor, typesetter, designer, publicity manager, copyeditor, and so on; someone has to pay for the software, the office space, and other expenses. Traditionally those costs have been covered by subscriptions, but because academic journals have a comparatively small audience the subscription prices are quite high. They’re typically paid not by individuals but by institutions, or in some cases they are subsidized by scholarly associations for their members—and in those cases the membership fees often cost as much as the journal subscription would. So there is a huge paywall between academic journals and their readers; being employed by an academic institution that subscribes to the journals one needs takes down that paywall, but only for academics who manage to land such positions. Trans and queer studies in religion are fields that until relatively recently have been risky areas of specialization, both because of a rigid and uninformed resistance to thinking about religion in many queer studies and trans studies circles and because of an unthinking acceptance in many religious studies circles of a widespread (and grossly inaccurate) Global North/Global West narrative about trans and queer folks being uniformly secular. Add these paired biases to the transphobia, homophobia, and biphobia that continue to plague much of academia, combine it with an already devastating job market for emerging scholars, and the result is a subfield with a significant number of contributors who are academically unemployed or under-employed—and who therefore have no access to academic journals.

“Founding a journal that can only be read by people who’ve managed, though both luck and privilege, to become part of academic institutions, or that can only feature the writings of such people, is important, but it’s not sufficient as justice work and therefore, to my mind, it’s not sufficiently queer or trans.”

But the problem is not solved by open access alone, because the standard open access model transfers the cost of publishing from the reader to the author. The subvention (author-paid cost) for open access for a single journal article is often in the low thousands of dollars. This is per article, and at research-focused schools scholars often publish at least two articles a year. So the paywall for authors in a conventional open access model is in fact far higher than it is for readers in a subscription model. For our field, conventional open access doesn’t solve the problem; thus, we’re making an enormous effort to launch the journal on a fee-free open access model, with no paywall for either readers or authors.

You can see the problem this raises, of course: Who pays for the publishing? Well, in the short term, we do. The press with which we’re hoping to publish estimates the cost of fee-free open access at $30,000 per year for the first five years of the journal’s existence. Because print copies of the journal will be offered at the usual subscription rates, we and our editor are all hoping that over time the journal will bring in enough subscription revenue to partially offset these costs, and we’ll be able to build a sustainable, long-term model for removing all of the paywalls in academic journal publishing. For now, though, we’re working very hard to find $150,000 in order to launch the journal.

How has access to grant funding influenced the trajectory of this work? Do you have advice for junior colleagues about where to start and how to gradually think more ambitiously as their projects evolve?

Grant funding has allowed us to dream bigger, to build not what was possible but what was right. Working in a field that represented a major career risk when I was in graduate school, I’ve learned to build things on a shoestring. So yes, we could have planned the journal and built the initial double issue without the May workshop. We could have contracted the journal on a conventional subscription model, and if we’d done so it would have already been under contract and the first issue would be coming out in a few months. And it would be prominent, an important new journal, a feather in our caps. And it wouldn’t do the work we want it to do. I’m one of those thinkers who believes that queer studies work and trans studies work must be, by necessity, justice work. Founding a journal that can only be read by people who’ve managed, though both luck and privilege, to become part of academic institutions, or that can only feature the writings of such people, is important, but it’s not sufficient as justice work and therefore, to my mind, it’s not sufficiently queer or trans.

“The UCHRI grant, moreover, functioned as seed money to demonstrate the importance of our work and the UC system’s investment in it, both literally and figuratively[.]”

Grant funding allowed us to gather a group of queer and trans studies scholars who’ve been isolated throughout the pandemic, to rekindle connections between them, to bring oxygen to the fires of their inspiration, to continue our efforts to bring the journal into being through collaborative, community-based processes, and to enable networking for our graduate students while also modeling for them what a supportive intellectual community looks like. The UCHRI grant, moreover, functioned as seed money to demonstrate the importance of our work and the UC system’s investment in it, both literally and figuratively; it formed an important part of our case to the Henry Luce Foundation for additional funding, and Luce bridged the gap between the UCHRI funding for the workshop and our total budget. In turn, we’re hoping that the Luce grant will serve as an indication to other grantmaking organizations—and perhaps to the Luce board itself—that our project is worthy of additional attention and funding, especially in these times of waning justice.

As for advice to junior scholars, I guess I would say to follow your passions and build your dreams, in community with others whenever possible. That sounds like inspirational-speaker language! But it’s the advice I give my graduate students as well. Academic work is hard and often thankless. Sometimes the work we really care about doesn’t only go unrewarded; sometimes it’s actively punished by our institutions. So if the work is rewarding to do, in and of itself, and if in the process of doing it we build spaces that support us and establish communities of care that sustain the work, then we have the resources we need regardless of what the institutions around us choose to make of us, as well as the resources to sustain our lives and careers if the work costs us our jobs. Funders are often excited by creative visions for our collective future, and fund managers’ job is to build bridges between visionaries and the donors who want to bring their visions to life. Sometimes that means having to do significant translation, so have conversations with funders that help you and them identify how your goals can interweave.

I noticed the language about “work boundaries” in your email signature – can you talk a bit about how you maintain them for yourself and how you encourage a culture of a healthy work/life balance as the chair of your department?

Oh gosh, you’re asking this of a department chair with an infant and a 2-year-old whose family is still on COVID lockdown! But I suppose who better to ask than someone whose boundaries are challenged multiple times a day. I have long been committed to the idea that justice work needs to be sustainable over a lifetime and longer, because that’s how long the work takes. If I want to be teaching, researching, writing, and organizing when I’m in my 70s, I need to make all of that sustainable now. If I want to be able to be really present with the work, I need to create and fiercely defend spaces where I’m not present with it.

What constitutes “sustainable” and “balance” is different for each person, and I believe people need to have the space to define that for themselves. As a department chair, a colleague, a teacher, and a mentor, I also believe that part of my job is to help people defend those boundaries. And I’m keenly aware that there are many ways in which people communicate norms and expectations, and many ways in which others infer them whether or not the communication was intended. As a department chair and a senior scholar, I am setting a tone and providing a model with everything I do, and if I want to communicate clearly that I value sustainable, just labor practices, I have to do so directly, both through words and through actions. Thus, among many other strategies, I’ve adopted from other scholars the practice of putting a statement in my signature line that explicitly spells out my hope that people will reply to my emails at a time that is sustainable for them.

Banner image credit: Robert Katzki